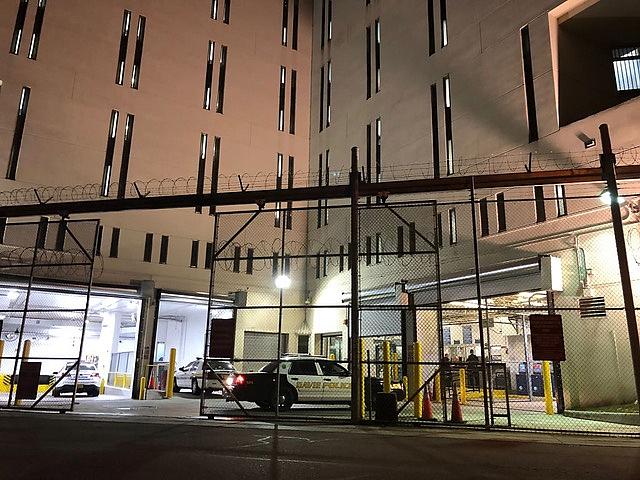

Health care in SoCal’s county jails: Cruel and unusual punishment?

(Photo: Michele Eve Sandberg/AFP/Getty Images)

More than 450 inmates have died in county jails in Los Angeles, Orange, Riverside and San Bernardino counties in the past decade — some at the hands of others, but the majority from health conditions, drug overdoses and suicides. Many more inmates have suffered from medical and mental health issues.

How much of that suffering would have been preventable if county jails had better health care systems?

A recent report from the Orange County civil grand jury suggests the number could be significant. Jurors studied 34 deaths over a three-year period and concluded that almost half of those inmates could have made it out alive if they’d received better care.

In one case cited by the grand jury, an inmate who was booked late on a Friday night and didn’t get an initial physical exam soon began to cry from persistent pain. The inmate got pain medication but the on-call doctor wasn’t consulted. Instead, an appointment was scheduled for Monday morning. The inmate died from massive internal bleeding caused by an aortic tear.

Riverside and San Bernardino counties were accused in lawsuits of providing such inadequate care in jails that it constituted cruel and unusual punishment; both counties settled and are now legally bound to make major changes. Riverside County has been phasing in its plan over the past three fiscal year — changes that officials say will cost the county $40 million a year, straining budgets and leading to controversial efforts to find savings elsewhere. San Bernardino County’s changes have just begun.

Los Angeles County jails have also been plagued by criticisms of their health care, but this year the county began an effort to overhaul the system. The goals are ambitious: to not just take better care of inmates but to help them learn how to manage their own care after they’re released as well.

Ironically, a law intended to improve health care in California’s chronically overcrowded state prison system is frequently blamed by county officials for worsening their problems. Before the law known as realignment took effect in 2011, any inmate sentenced to more than a year would go to a state prison. Since then, many of them are instead getting sent to county jails, creating challenges for officials not used to providing long-term care.

For my 2018 Data Fellowship, I plan to look at the state of health care in the four county jail systems within the Southern California News Group’s coverage footprint, paying close attention to the problems created or exacerbated by realignment, and what’s being done to improve care.

Data will come from state records, court records, death investigation reports and county budgets. Of course, the real stories will come from the people those records lead me to.