The Health Divide: The devastating toll of wildfires on health is far greater than we think

(Brian van der Brug / Los Angeles Times via Getty Images)

Everyone thought drugs killed 25-year-old Preston Weinberg.

He died alone, crouched in the shower of his Los Angeles apartment, sometime between Jan. 9 and Jan. 11 of this year. No water was running. Police found small quantities of MDMA and cocaine in his home. Outside, smoke choked the air as two catastrophic wildfires tore through distant neighborhoods of the county.

His parents, who live in Pennsylvania, got the heart-shattering call. His father remembers being told their son died from an overdose. They included that in his obituary. To omit it or hedge by calling it an “apparent” overdose “felt false at the time,” his mother, Kimberly Weinberg, recalled.

And so the family was shocked three months later when the coroner issued the autopsy report. Preston had no drugs in his system. He died from an acute asthma attack. His family believes the fires triggered it.

Officially, the catastrophic Palisades and Eaton fires killed 31 people. But recent research suggests the toll may have been as high as 440, once you count more than those killed in the flames and include people who died for fire-related reasons: respiratory and heart ailments exacerbated by toxic smoke, for example, or delays in medical care as the infernos raged.

The report adds to an alarming pile of evidence that more frequent, intense and destructive fires fueled by climate change cause far more death and illness than official tallies capture. The health threats persist long after the flames are extinguished and journalists move on to the next big story.

Researchers reported in Nature last week that a staggering 354 million people in North America and Europe were exposed to hazardous air pollutants from the 2023 wildfires in Canada, the worst in the country’s history. The researchers attributed 5,400 deaths on the two continents to acute smoke exposure and 64,300 deaths — including 33,000 in the U.S. — to long-term smoke exposure from the thousands of fires that burned over eight months.

The fire that ravaged Lahaina on Maui in August 2023 also had severe health consequences. That month alone, suicides and overdoses skyrocketed by 97% on the island, and by 46% across Hawaii, a national team of researchers recently reported.

In the 14 months that followed, reports of heart disease, respiratory ailments and depression on Maui spiked, according to a study led by researchers at the University of Hawaii.

Nobody is immune, but the risks are greatest for people who have preexisting conditions — notably older adults, low-income people and people of color.

We’re also learning that health problems may not show up for months or years. Air pollution is known to raise the risk of dementia, but a study of nearly 28,000 older Americans found that fine particulate matter from wildfire is more dangerous than exposures from other sources, such as truck fumes or coal plants. That may be because an inferno releases such high levels of toxic components in a sudden burst. Those who work low-wage jobs outside are especially exposed to breathing in particulates.

Another study shows that prenatal exposure to air pollution is associated with changes in fetal brain structure.

“Pregnant women who inhaled hazardous wildfire smoke during those January days in LA may give birth to children with subtle but significant alterations in brain development,” Burcin Ikiz and Clayton Page Aldern, coordinators of the Neuro Climate Working Group, wrote in STAT in August. No one yet knows how those brain changes may affect learning and behavior as children grow up.

Nor is foul outdoor air the only hazard.

Soil samples collected from burn areas in LA and other wildfire sites have unearthed hazardous levels of heavy metals and other toxic chemicals, such as lead and arsenic.

And even after the January Los Angeles fires were out, UCLA researchers found high levels of volatile organic compounds — invisible carcinogens such as benzene — inside homes in the burn areas. When smoke penetrates homes, bedding, carpets, and other belongings can absorb these chemicals and then release them into the air over time.

“The risk is people start going back into their homes and they’re exposed to this toxic soup on an ongoing basis,” said Michael Jerrett, a professor of environmental health studies at UCLA who took part in the study and is now co-leading research on the long-term health effects of the LA fires.

In a JAMA editorial, epidemiologist Sonia Angell wrote that wildfires and other climate-fueled disasters “are communicated as events, with a beginning and an end.” That minimizes the impact. By taking a fresh look at deaths in LA, demographer Andrew Stokes and colleagues have begun to reveal the depth and scale of the losses.

Stokes, an associate professor at Boston University, used the WONDER database from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention to see how many people died in Los Angeles County in 2018, 2019 and 2024. He skipped 2020-23, atypical years because of COVID. The Palisades and Eaton fires erupted on Jan. 7 and burned until Jan. 31. Stokes looked at all deaths in the county from Jan. 5 to Feb. 1.

Based on those earlier years, modeling showed that 5,931 deaths would be expected during those weeks of 2024. Yet 6,371 people died in that time. Stokes didn’t examine what caused all these deaths but says the excess can be attributed to the fires.

Wildfire smoke, of course, can waft for hundreds or thousands of miles. Had Stokes looked at fatalities beyond LA County or past the beginning of February, he may have found the toll was even higher.

Stokes used the same methodology during the COVID pandemic. He worked with journalists from The Brown Institute for Media Innovation and MuckRock’s Documenting COVID-19 project to uncover the hidden toll of COVID deaths in Hispanic, Native American and Black communities. He provided numbers; reporters told the human stories.

Stokes said similar collaborations with journalists can expose how deadly urban wildfires really are.

“We can say that there were 440 excess deaths due to the wildfires in Los Angeles, but we can't really explain why,” he said. “So the next step from the journalism perspective would be to call the coroner’s office, call the medical examiner, call local providers and physicians or frontline workers to try to really understand what the heck happened and why. Why is our death count so much larger than the official one? What are some of the local stories around those death counts?”

One story is Preston Weinberg’s.

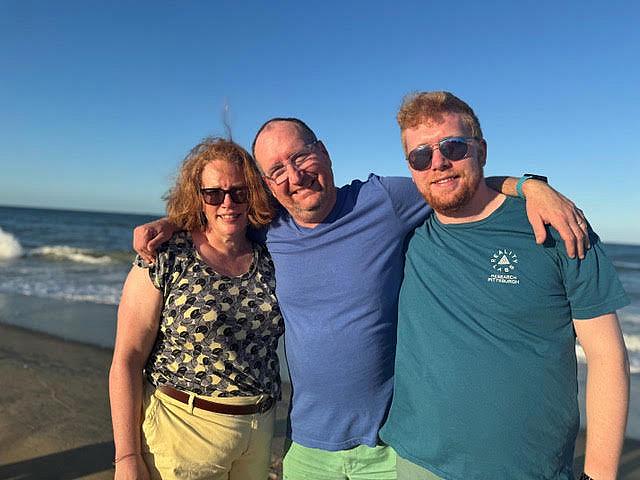

Preston Weinberg, at right, with his parents Rick and Kimberly Marcott Weinberg on a family trip to Virginia Beach in 2024. Preston died from an asthma attack during the LA wildfires in January.

(Courtesy photo)

Preston lived on West Pico Boulevard, about 19 miles away from the Eaton fire and 16 miles from the Palisades fire. He was working at home because of the blazes but went out for burritos with a friend the night of Wednesday, Jan. 8.

A friend later told his mother, Kimberly, the air was so bad he could feel the particles.

On Saturday, Preston didn’t show up for a weekly Pittsburgh Steelers watch party or pick up his phone. A friend went to his apartment, got no answer and called police. Preston was declared dead around 4 p.m. His mother wonders if he got into the shower to try to breathe easier.

There is no way to measure a parent’s grief for the loss of a child. But the initial report of an overdose compounded it. “Honestly,” Kimberly told me, “the fact that it was a ‘natural death’ has made our grief less complicated.”

When she read about the study by Stokes, she emailed him to thank him and his colleagues for their work. She told him a bit about her son.

“While I have been mourning him, I have also wanted his death to be recorded as being from the fires,” she wrote. “I think it’s important in the recording of climate change.”