The Health Divide: Giving low-income families $1,000 a month boosts their stability and prospects

Photo by Russell Shaw Higgs via Flickr/Creative Commons

Imagine receiving an extra $1,000 a month over the next year. What would you spend the extra funding on?

A car? Season tickets to watch your favorite NBA team? Would you take an exotic seven-day cruise?

Or maybe you’d do something less exciting but more practical, like using those unexpected funds on food and rent.

Some urban cities across America are experimenting with guaranteed income programs to boost people out of poverty and help them afford housing and food.

While the programs that provide anywhere between $500 to $1,000 of additional funding to a select group of low-income people have been met with mixed reviews, participants say the programs provide them with a safety net needed to get them from month to month.

The concept of guaranteed income — also known as universal basic income programs — is not new.

Such programs are being tested in cities across America, from large cities like New York to cities as small as Yellow Springs, Ohio, with a population of 3,700.

While the pilot programs alone can’t end poverty, they do help reduce housing and food insecurity. Most of the participants have used the extra income on housing and food. Since most families were listed as “cost-burdened,” the money helped their budget immensely, allowing them to pay their rent or purchase more food.

Studies have shown that housing and food security decrease poverty by increasing stability. We know eating three healthy meals a day and having stable housing can go a long way to breaking the cycle of poverty.

Pilot program in Austin, Texas shows promise

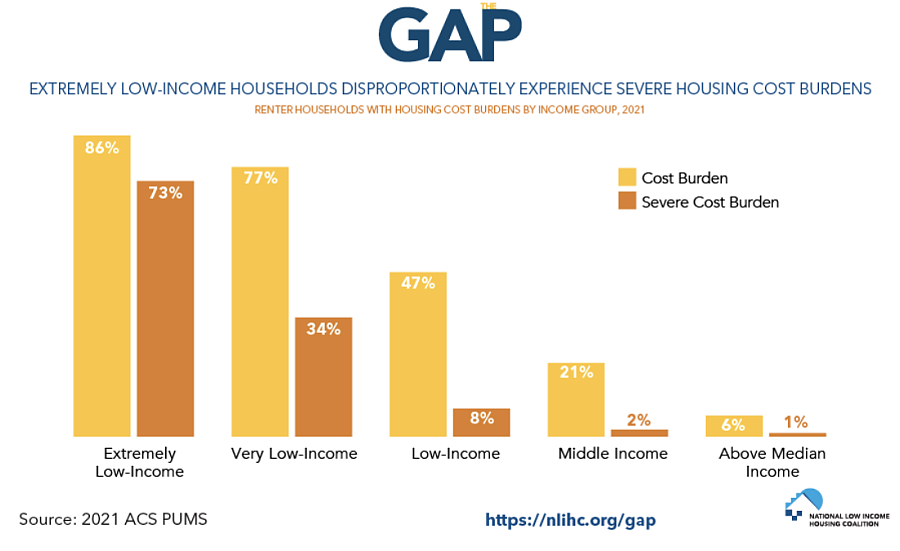

Guaranteed income programs fill a need because 52% of renters and 23% of homeowners were cost-burdened in 2022, according to the U.S. Census Bureau.

According to the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, a household is cost-burdened when it spends more than 30% of its income on rent and utilities, and severely cost-burdened when it spends half of its income on these expenses.

Austin was the first city in Texas to launch the guaranteed income program in May 2022. The program served 135 low-income families, with each family receiving $1,000 monthly.

A January story by the Business Insider showed how Taniquewa Brewster benefited from the program.

Brewster, a single mom of five, said she struggled to make ends meet before the extra $1,000 a month. Her kids were in school and needed extra money for activities and other expenses.

Her family’s situation improved in September 2022 when she enrolled in the program. She called the program a lifeline because she had racked up lots of medical bills after an eight-day hospital stay. The extra $1,000 allowed her to pay off those bills and buy medication she could not afford had it not been for the stipend.

In addition to helping her pay off her medical bills and pay for medications, Brewster said having the additional money allowed her to think about her future instead of being in day-to-day survival mode.

Brewster, who is African American, started in a trade program that helped her to become a leasing agent.

“It’s helped me fight for tenants’ rights through volunteer advocacy groups,” she told KXAN, a local NBC affiliate.

Some critics warned that if you give low-income residents $1,000 a month, they will spend the money on drugs and alcohol and stop working. Instead, participants used the money for rent, food, medical bills, and help their children.

In January, the Urban Institute analyzed how Austin’s guaranteed income pilot program changed the lives of people like Brewster, and here is what they found:

- By the end of the 12 months, “pilot participants had become substantially more housing secure.”

- Participants’ employment remained relatively stable throughout the pilot.

- Nine percent of respondents reported that they reduced time spent working due to the funds, with half saying they spent the extra time on skills-building to secure a higher-quality job and the other half taking on additional care commitments, such as spending more time with their children.

- Seven percent reported increasing their time spent working due to the cash, with most saying they used it to break down barriers to better jobs (lack of transportation, for example).

“Since I don’t have a vehicle, I take Ubers and the bus (to job sites),” said one security guard who worked at multiple job sites daily to make ends meet. “Before I started receiving the pilot cash, sometimes I didn’t have enough money for Uber, and I’d have to take only the bus to get to more than one job. It’s hard trying to manage that.”

Mental health and food security improved

One of the most significant changes noted in the Austin pilot program was how participants' mental health and food security improved due to the monthly stipend.

Participants’ mental health reached the highest level of improvement at the six-month mark, with the most notable gain being substantial relief from depression for 12% of participants, the Urban Institute reported.

The report showed that two measures — feeling anxious and depressed — remained at or near those six-month levels after the pilot.

The share of participants reporting that they could not “stop worrying” increased by 6% above the baseline by the end of the pilot because they were concerned about making ends meet once the pilot ended.

“Even some of those leveraging the cash to build skills or make new job contacts expressed doubt that they could fill a $12,000 gap in annual gross income with increased labor market income in such a short period,” the report said.

Reductions in food insecurity were significant during the 12-month pilot, and participants were notably more likely to be able to afford balanced meals because of the cash payments. Most families had faced food insecurity before receiving their first stipend.

In short, the pilot worked the way it should. It provided low-income families with money to keep them from falling deeper into poverty. Children were able to eat more well-balanced meals. More single mothers could spend more time with their children, pay off medical bills, and not worry about their rent being paid.

Participants could also consider their future and take classes to improve their lives and earn higher-paying jobs. Or afford an Uber to get to a second job instead of just being able to work one job.

People’s mental health also improved because they were not as stressed worrying about how they would make ends meet. The study didn’t measure this, but one could even assume their family life was probably better because the mother or father felt better about themselves.

I’ve been on panels discussing the difference between a hand up and a handout, and this pilot program is the definition of a hand up, where families used the money for good, and there were few incidents of fraud or lavish spending.

The downfall was that the participating families knew the year-long program would end and that their lifeline would be snatched away, potentially sending them back into poverty.

That is not right. There must be a way to keep these programs going for over a year. Imagine how much Brewster’s family would benefit from a five-year boost.

I hate to imagine what life will be like for her family if she suffers another medical issue.