Four ways to make streets safer in Watsonville

The story was originally published by the Santa Cruz Local with support from our 2025 California Health Equity Fellowship

Bike shop owner and cycling advocate Jules Mandujano walks across Main Street in Downtown Watsonville.

(Amaya Edwards — Santa Cruz Local / CatchLight Local)

WATSONVILLE >> Watsonville is one of the deadliest cities in the state for cyclists and pedestrians. Since 2008, 30 people have died walking or biking in Watsonville.

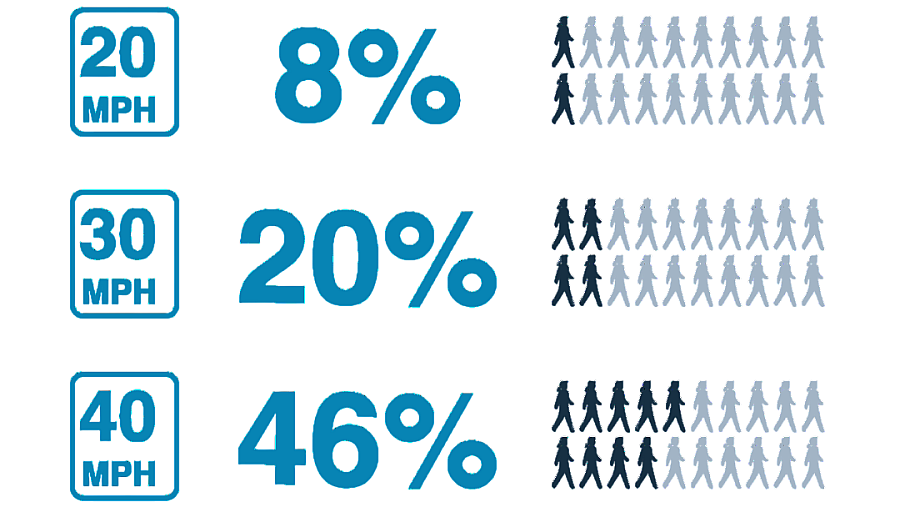

Research indicates the most effective way to keep pedestrians and cyclists alive is to slow cars — 5 mph can make the difference between the emergency room and the morgue.

To make Watsonville streets safer for walking, the city could lower speed limits, design roads to slow cars, hire more engineers and reroute a state highway away from Downtown.

Likelihood of death for pedestrians hit by cars, by speed.

(Safe Transportation Research and Education Center).

For years, speed limits across the state have crept up as state law required speed limits to be 85% the average driving speed.

A 2021 state law allows local governments to lower speed limits on some roads by 5 mph. City staff plan to commission new studies to determine where speeds could be lowered, said Watsonville Assistant Director of Public Works Murray Fontes.

Fontes said it will likely take more than new limits to slow cars. Lowering a road's posted speed limit by 5 mph decreases vehicles' average speed by 1-2 mph, or 3 mph if consistently enforced with traffic tickets, research suggests.

Enforcement has been difficult for Watsonville police — for 18 months, one officer was dedicated to issuing traffic tickets, said Watsonville Police Capt. Mish Radich. The force recently hired a traffic sergeant, he said, and hopes to hire another officer to focus on traffic.

But police enforcement "can raise equity issues" for people concerned about police harassment, and for low-income people that can be disproportionately affected by fines, said Tommy Travers, transportation planner for the Santa Cruz County Regional Transportation Commission.

Though research suggests traffic enforcement can be useful in short-term safety improvements on high-injury streets, "ideally, all streets are designed for a safe speed for all users, so that you don't have to rely on signs or enforcement," Travers said.

Design roads to slow cars

Since 2013, all 25 of Watsonville's cyclist and pedestrian deaths were on seven roads.

Two are state-controlled highways that host more than 1,000 truck trips and more than 20,000 car trips daily. Five are city-controlled streets widened in the 1990s and 2000s to accommodate a rapidly growing population.

Removing vehicle lanes on wider streets — called a "road diet" — can encourage cars to travel more slowly and make walking and biking safer. One analysis found that road diets reduce crashes by 19% to 47%.

Road diets often slow cars while keeping traffic moving smoothly, but some road diets on streets with heavy traffic may worsen congestion, according to traffic engineers.

Watsonville's first road diet is planned for Main Street from Freedom Boulevard to Beach Street. The stretch is part of Highway 152, which is managed by the California Department of Transportation, or Caltrans. It isn't expected to cause more congestion, according to a Caltrans analysis.

The Watsonville City Council voted to support the plan in 2022, and it is expected to be completed in 2033.

In 2015, the council considered a similar plan to swap two car lanes for bike lanes on a city-controlled portion of Main Street from Beach Street to Riverside Drive. It faced opposition from some residents and council members about worsening congestion and was later dropped.

That plan could be revived and was included in the city's long-term Downtown Specific Plan adopted in 2023. It also envisions new bike lanes and narrower car lanes on other downtown streets, and a roundabout at Main Street and Freedom Boulevard.

Similar changes could be considered for Freedom Boulevard, one of Watsonville's most dangerous streets for cyclists and pedestrians. This year, local nonprofit Ecology Action surveyed residents on their concerns about the street. Their feedback will be incorporated into a proposal for a new design, possibly with a road diet, this fall.

Reroute the highway

Jules Mandujano, an avid cyclist and owner of bike shop Watsonville Cyclery, is skeptical of plans for a road diet on Main Street or Freedom Boulevard. He worries it would increase congestion and divert cars onto smaller streets near schools and homes. "Either it stays the way that it stays, or we send traffic somewhere else," he said.

The only way to improve safety, he said, is a more ambitious plan — routing Highway 152 around the city, instead of through it.

It's an idea the city has considered before — in 2011, the city council voted to pursue a process to request Caltrans to transfer the part of Main Street it manages to the city. An alternative route could divert trucks and through traffic, possibly to Airport Boulevard on the outskirts of the city. But in 2015, the council abandoned the process, in part because city staff advised it would be too costly to maintain the street.

Last year, the city and Ecology Action won a grant to study the environmental impacts of truck traffic through Watsonville, and consider alternate routes. But last month, the federal "One Big Beautiful Bill" approved cuts that rescinded that grant. Although Fontes said he still wants to study alternative truck routes, there's currently no budget or staff to do so.

Hire more engineers

Staff is a constant limitation to Watsonville's street safety efforts.

In 2018, Fontes floated potential redesigns for Freedom Boulevard. But "other staffers left, I got promoted and took on more responsibilities, and that was something that went on the back burner," he said. It was another five years before the city won a grant for the outreach and design work.

Ten transportation projects were delayed in the fiscal year that ended June 2024, in part because staff didn't have time to work on them, according to a city report of Measure D sales tax spending.

Watsonville has been without a traffic operations manager for nearly two years, and two of the city's civil engineer positions have been vacant since 2022. In Fontes' 25-year tenure, the city has never had a civil engineer dedicated entirely to transportation, he said.

By contrast, the city of Santa Cruz has a transportation division with three civil engineers and four other staff.

Watsonville farms out most of its transportation projects to consultant Jaime Rodriguez, who leads Pleasanton-based Smart City Signals. But ideally, Rodriguez said, he'd work alongside the city's own engineers and get the job done faster, he said.

Signs of change

Despite the challenges, incremental changes are making streets safer in Watsonville. Rodriguez has helped improve crosswalks and bike lanes as part of the city's plan for safety fixes near schools. A long-planned bridge over Highway 1 at Harkins Slough near Pajaro Valley High School is set for construction late this year or early next.

While repaving Green Valley Road, Freedom Boulevard and Airport Boulevard, city staff are restriping roads to make lanes in some areas slightly narrower. Research indicates that drivers naturally slow on narrow lanes. With the extra space, the city is building bike lanes.

A state grant is set to fund a citywide plan for bike lanes, sidewalks and other improvements. The plan would qualify the city to apply for future funding to build the improvements as soon as next year.

The grant could "help Watsonville begin to do major transformation," Rodriguez said.