The Health Divide: Telling the stories of cancer’s toll on Black men could help close the gap

Image

(Photo By Liz Hafalia/The San Francisco Chronicle via Getty Images)

Published on

August 25, 2025

Everyone has a cancer story.

Through firsthand experience or from being there as a family member, close friend, or coworker who goes through it themselves.

My story is about losing my father to pancreatic cancer in 2018, and just six months later, I lost my mother to cancer as well. I also lost my aunt to colon cancer and my uncle to brain cancer.

My cousin has been battling leukemia for the past seven years.

Lastly, when I had my first colonoscopy last year, the doctor removed five polyps, two of which were deemed cancerous.

Roy S. Johnson, a columnist for AL.com since 2014, has two cancer stories. The first began in 1969, when he was 11 years old. His father, also named Roy, was in the hospital. Since they didn’t allow children into hospital rooms in those days, he didn’t know why his father was there.

When his mother visited his father in the hospital, Roy and his younger brother waited in the lobby or were left at a friend's home.

“It wasn’t for children to know,” Johnson told me, while we were in Cleveland at the National Association of Black Journalists convention in August.

The only time Johnson and his brother got to see his father again was on Sunday, January 12, 1969. He never forgot that day because it was Super Bowl III, and his father, mother, and brother watched the black-and-white television in his father’s hospital room as the underdog New York Jets beat the Baltimore Colts, 16-7.

The following Sunday, Johnson’s father died. He was 66. The cause of his death was prostate cancer.

Johnson’s second cancer story occurred earlier this year, after he went in for his routine checkup. Days later, his doctor called him and told him he also had prostate cancer.

Johnson detailed his cancer journey in a column for AL.com. titled, “I have prostate cancer — and the faith to beat it.”

As a board member of the American Cancer Society in Alabama, Johnson was aware that prostate cancer is the most frequently diagnosed cancer in men and the second-leading cause of death among men in the United States.

As a Black man, Johnson also knows that one in six Black men will be diagnosed with the disease during their lifetime, and they are two times more likely to die from it than white men.

Additionally, men who have a father, son, or brother diagnosed with prostate cancer are up to three times more likely to develop the disease themselves.

“My father’s fate does not need to be mine,” Johnson said.

Tracing the roots of cancer disparities

In general, prostate cancer has good survival rates. However, African American men are more likely to be diagnosed at an advanced stage and face higher mortality rates from the disease. According to the National Cancer Institute, the prostate cancer death rate for Black men is about 36 deaths per 100,000 each year, compared with about 19 deaths per 100,000 among men overall.

The disparities in cancer outcomes between African Americans and their white counterparts have been linked to health care access and socioeconomic status.

Research is starting to show that when white and Black patients have the same access to care, their outcomes for most cancers are more closely aligned, and age rather than race then becomes the main factor in outcomes. But that’s not always true for all cancers.

Socioeconomics also plays a significant role in health treatment. Being able to afford health insurance, copays, medications, and take time off work for treatment is a cost many African Americans cannot afford. Epidemiologists have found that where you live can influence your risk of getting and surviving cancer, and neighborhood-level factors may even affect the expression of genes that play a role in cancer, according to emerging research.

Johnson urges health journalists to delve deeper into the multifaceted topic of cancer, a disease that impacts countless lives and families. By telling these stories, journalists can help inspire awareness and foster a culture of proactive health care among the public.

“The doctor called.”

After his father died, Johnson realized the importance of prioritizing his health.

He committed to an annual physical and regular exercise, understanding that taking proactive steps was essential for his well-being.

“I have a record of annual checkups that goes back as far as I can remember, and that includes blood work, too, and I’m 69 now,” Johnson said.

After his annual checkup, Johnson received a follow-up call from his doctor, informing him that his prostate-specific antigen (PSA) test results showed an increase.

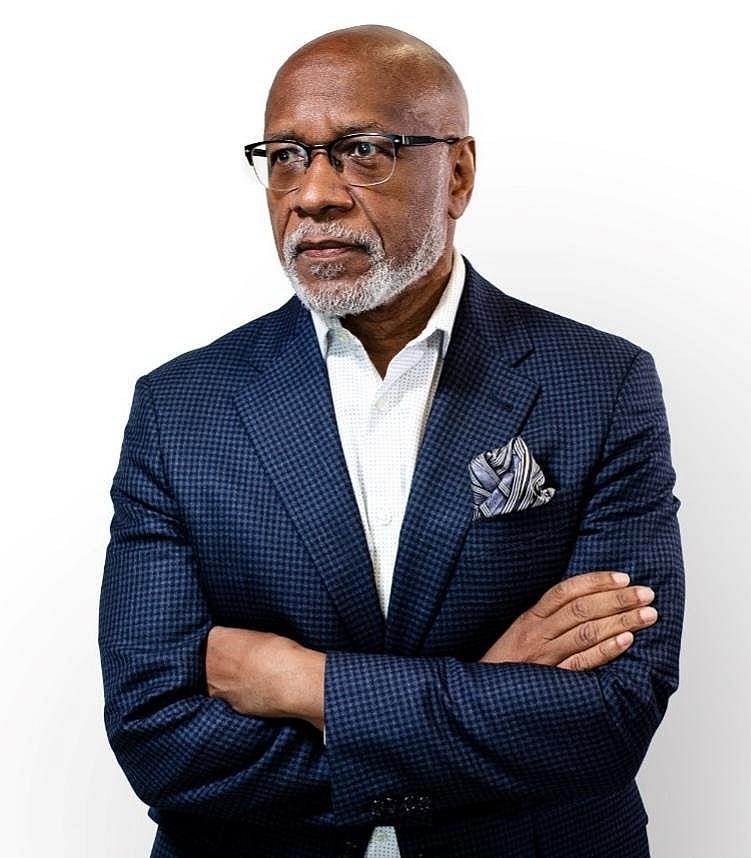

Image

Roy Johnson.

A few weeks later, Johnson went back to his doctor, got additional tests, and had a biopsy, where the urologist snipped 12 tissue samples of his prostate for testing. They told him they would have the results within 10 days.

Waiting is the worst, Johnson said.

When the urologist's call on July 3 finally came, Johnson was attending an event in New Orleans, supporting his wife at a reception for her nonprofit, the Black Women’s Mental Health Institute.

He stepped outside the reception and answered his phone. The urologist said, “Hello, Mr. Johnson, unfortunately …”

“I can’t recall what the doctor said after that because my mind went blank for a moment. For me, it wasn’t the word 'cancer' that affected me; it was the word 'unfortunately,'” Johnson said.

The urologist told Johnson that the test found cancer.

“Hearing those words shifts your thinking because you believe this is the beginning of the end. And although we’re all going to die, there's something about hearing the word ‘cancer,’” Johnson said.

The urologist told him that his cancer is treatable and that only about 3% of people with prostate cancer die from their cancer. Johnson thought back to his father, who was only three years younger than him when he died from prostate cancer.

He also thought about how he was going to tell his wife.

Johnson didn’t share his news with his wife during her gala because he didn’t want to ruin her evening.

He waited until they were getting ready for bed.

“The doctor called. I have cancer.”