How do you tell the story of gentrification and health? Reporters find fresh ways to make the connection

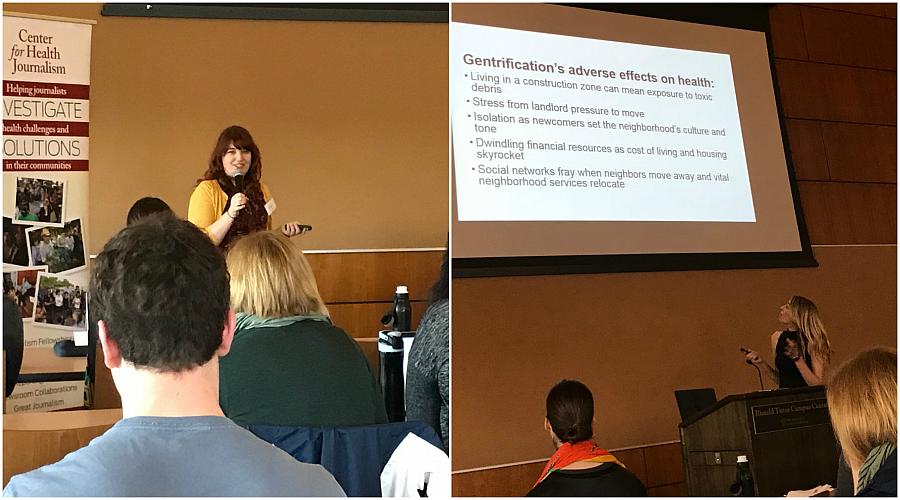

Bethany Barnes of The Oregonian, left, and Erin Schumaker of HuffPost talk to 2018 California Fellows about reporting on gentrification. (Photos: Chinyere Amobi/CHJ)

When Bethany Barnes began to cover evictions and gentrification in Portland, she wanted to approach the issue in a different way. As an education reporter for The Oregonian, she was uniquely capable of finding and telling the stories of how children and schools have been impacted by waves of neighborhood change.

Sometimes, kids were just disappearing from classrooms, without warning, teachers said. That was the case with Malik, a fifth-grader. After years attending the same school, where teachers found him deeply frustrating and deeply likeable, said Barnes, he simply vanished. Her investigation of high-churn schools became “Reading, Writing, Evicted,” a series of stories and videos about the effects of Portland’s gentrification on children. Barnes visited school classrooms where a child was leaving or joining every few days. “In Oregon’s largest school district, there are more than 1,700 students who go through three or more schools between kindergarten and eighth grade,” Barnes told fellow reporters at the 2018 California Fellowship last week.

All that moving can create havoc in kids’ lives, but also in the lives of their fellow classmates and teachers. One teacher Barnes interviewed revealed that six kids had arrived in her class, and seven had left. “It’s hard to learn how to work together if you’re working with people who are constantly changing,” said Barnes.

For Erin Schumaker, a senior reporter at Huffington Post, the path into gentrification stories was through health. Her fellowship project, “Diagnosing Gentrification,” is an investigation of the ways changing neighborhoods can actually make people sick. Initially, Schumaker hoped to create an index based on race, rent, income to see which New York City neighborhoods were gentrifying the most, and then compare that index with health data. But she quickly realized that strategy wouldn't work. “The neighborhood was constantly changing, so it wasn’t possible to get the statistics I needed,” she said.

Then, Schumaker caught a lucky break: the New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene published data using emergency room data that tracked hospital visits in different neighborhoods. As Schumaker reported, “These researchers found that New Yorkers who moved from gentrifying neighborhoods to non-gentrifying, poor neighborhoods had a bigger rise in hospital visits in the five years after their displacement. Hospital visits among residents who were displaced rose 63.9 percent between 2006 and 2014, compared to 18.7 percent among residents who stayed put.”

Schumaker used the data to create maps and graphics to prove the central theme of her reporting — that gentrification impacts health in tangible ways.

Schumaker found there are several ways gentrification can affect health. First, the noise and pollution coming from construction zones can be harmful. Residents also deal with stress when a landlord pushes them to move out so wealthier tenants can move in. They may not be able to afford food at new markets in suddenly upscale neighborhoods. And finally, social isolation and loneliness can have a real impact when friends and family move far away.

Finding people who fit the story proved difficult. “I thought my biggest struggle would be to find data, but my biggest challenge was finding people,” Schumaker said. She employed some creative ways to find sources, including knocking on doors and passing out fliers, and renting a booth at a health fair to talk with neighborhood residents in the Crown Heights neighborhood of Brooklyn, where her project focused its attention.

“On my fliers, I couldn’t write: ‘Is gentrification a health problem?’ so instead I just wrote: ‘How is your rent?’” Schumaker said. She advised journalists to return to sources time and again to check in. She visited one building in Crown Heights 12 times, knocking on doors and attending meetings.

Barnes also used some creative strategies in finding the children whose lives and schools were upended by gentrification. To locate Malik, she tracked his address to a new school district and showed up on his doorstep on a weeknight. She also took the bus with a child who traveled for hours across Portland so he could attend his old school. She also has some tips for other journalists writing about kids in adverse circumstances. Barnes was firm in insisting these children were not victims — her stories are about what children and families are doing under really challenging circumstances.

“Consider the framing,” she told the group of California Fellows this week. “These kids don’t want to throw a pity party for themselves.”

Read Bethany Barnes' fellowship series here, and find Erin Schumaker's reporting here.