As resources for families remain in short supply, child welfare referrals become more common

This article was originally published in the Nevada Current with support from our National Fellowship and the Fund for Reporting on Child Well-Being.

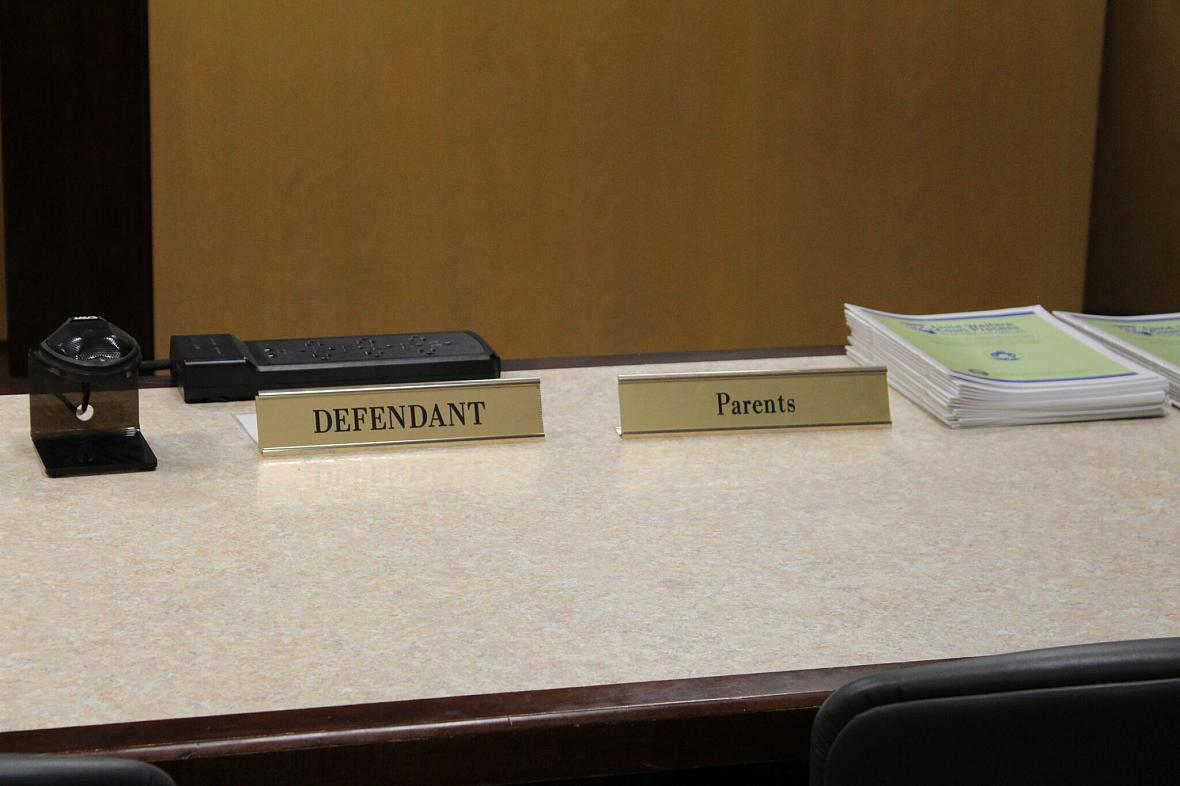

(Photo: Michael Lyle/Nevada Current)

Before a family begins the process of complying with case plans outlined by agencies in order to keep their children, before protective services intervenes to remove a child, and before a parent sets foot in a courtroom seeking to reunite with their children, child welfare cases begin with a referral

Last year there were nearly 41,000 referrals to the child protective services (CPS) throughout the state, according to data from the Nevada Department of Family and Child Services (DFCS).

The bulk of investigations are in Clark County, which received 30,484 referrals for abuse and neglect last year. Clark County Department of Family Services data shows the number was an increase from the previous year which received 29,671 reports.

Washoe County had 6,478 reports in 2024, up from 6,029 the year before.

“About 40% from schools, about 20% from law enforcement, about 20% from hospitals, and then the rest come from miscellaneous sources like individual citizens or other folks in the community,” said Ryan Gustafson, the director of the Human Services Agency at Washoe County.

Families who seek housing assistance or end up at shelters aren’t typically supposed to be referred to CPS, said Amanda Haboush-Deloye, the executive director with Nevada Institute for Children’s Research & Policy.

“They don’t have to report just based on the fact a family is going to a shelter asking for services,” she said. “Just like if a family shows up and applies for WIC (Womens, Infant and Children program) it doesn’t mean they are going to get a referral.”

There are some exceptions.

Washoe County operates a 38-private room facility for families with children called Our Place Shelter.

If the shelter runs out of space and families have no other housing options, the county can offer to pay for a hotel room. Accepting the assistance to stay in a hotel comes with an automatic referral to child welfare, said Sabrina Sweet, a human services coordinator with Washoe County.

A referral doesn’t mean a child will be removed from their families.

Even when a CPS case is opened, the county does “everything that we can to not open a court case,” said Tara Sterrett, a human services supervisor with Washoe County.

At the time of publication, Washoe County was still working on a data request from Nevada Current to determine the number of families who received CPS referrals after being placed in a hotel and if any later led to children being removed.

There has been a constant waitlist for family rooms at Our Place the last three years, Sweet said.

The number of families have fluctuated from 13 to 38, and the wait for a room can be from three weeks to 12 weeks, she said.

The county didn’t have any data on how many people declined services and a hotel room because of a referral to CPS.

“We have not done an analysis to that extent, but I will tell you that it is a constant conversation,” Sweet said.

Space and bandwidth

Both Clark and Washoe counties have expanded family shelter spaces since the pandemic, seeing a rise in families experiencing homelessness.

The high cost of rents and the lack of affordable places to live are driving people into homelessness in Washoe just like the rest of the state – as well as the country.

“One of the biggest barriers is affordable housing, especially for families,” Sterrett said.

The larger the family, the more challenging it becomes for them to find adequate housing.

“It’s really hard to find an apartment that’s going to be large enough that they’re going to be able to afford and sustain,” Sterrett said.

Seeing the need, Washoe opened Our Place Shelter in 2020 to offer shelter space to families as well as single adult women. The main homeless resource, the Cares Campus, predominately serves single adults.

“We don’t have any more space” at the Our Place, Sweet said. She was unaware of any plans to increase the budget for case management or expand the facility.

When Our Place reaches capacity, case workers can offer to pay for motel rooms for families with children.

Prior to that, the county helped the family find alternative housing options in lieu of a hotel stay, Sweet said.

“If somebody comes in, we put them on the waitlist, and we try really hard to help them find somewhere else to stay,” Sweet said. “If there’s another family member or somewhere else that the family could stay, then we put them on the wait list, and then they go stay with their family members, or whoever they’ve been staying with.”

There are three case managers that assist families at Our Place.

“We don’t have the bandwidth to go out into the motels,” Sterrett said. “Once we put them in a motel, we don’t really have the ability to go in and say, ‘Okay, now what is it that’s keeping you from being able to provide for your kids?’”

Child welfare services are able to come to the hotel to meet with families, do a formal assessment, conduct a safety plan, and determine needs while the family waits for a room to open at Our Place.

The county tries to “not minimize the fact that we are making the referral to CPS, but possibly minimize their fear of making the referral to CPS,” Sweet said.

Homeless services and child welfare services are housed within the same human services agencies, but that often doesn’t matter to families. It’s hard to shake the stigma that comes with a referral to child welfare, Sterrett said.

People hear CPS and “they get scared,” she said.

“We are still the county, regardless of whether we’re HHS (Health and Human Services) or HSA (Human Services Agency) or CPS or whatever the acronym is, we’re all the county, and that’s scary to people too, and people being willing to accept government assistance in any form sometimes is terrifying,” she said.

In the past, she said they’ve had families placed on the waitlist but opt out of staying at a hotel. The county has then lost contact.

Paying for the hotels have been “pretty helpful as far as keeping connected with those people, because we lose them when they get on the wait list,” she said.

Even if families in hotels are being evaluated by CPS, the county will work to find other solutions before removing children to foster care or seeking court involvement, Sterrett said.

“There might be some allegations about controlled substance use or domestic violence, but we do have grandma,” she said, adding the county would seek to temporarily place the children with family while CPS works with the family.

More resources needed

Recently, a nine-member family went to the Nevada Institute for Children’s Research & Policy seeking housing assistance.

When reaching out to service providers, Haboush-Deloye would ask if they would refer the family to CPS.

“If they said yes, I wouldn’t give them the family’s number, because I didn’t want them to lose their kids because they couldn’t find housing,” she said.

The institute had already done a safety assessment for the family and determined that the children weren’t at risk of any danger. The family just needed a place to stay.

The organization was eventually able to get the family housed and avoid CPS involvement.

Haboush-Deloye notes the irony is that sometimes social service providers don’t have the resources to prevent a family from entering homelessness or to address the underlying causes of housing insecurity.

Once they become unhoused, and potentially come in contact with the child welfare system, then resources open up.

“Oftentimes when you’re involved in CPS with an open case you have access to resources you don’t normally have,” she said. “You have access to assistance with child care or transportation. The day your case closes, those things go away.”

The problem comes down to a lack of resources in the community, in particular the need for more stable housing and rents people can afford.

It all comes back to “resources to keep them housed to make sure it’s sustainable and not just temporary,” she said.