How Food Assistance Cuts Can Impact Long-Term Health

The season of feasting and overindulgence may have officially arrived for many, but millions of less fortunate families across the country are facing fresh challenges in getting basic levels of food to the table, thanks across-the-board cuts in the federal food assistance program that took effect Nov. 1.

For the 47 million America Courtesy of the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities

With research showing that SNAP can make a lasting difference in the health and financial outlook of children, such cuts could leave lasting effects on the lives of the country’s most vulnerable families in the decades to come.

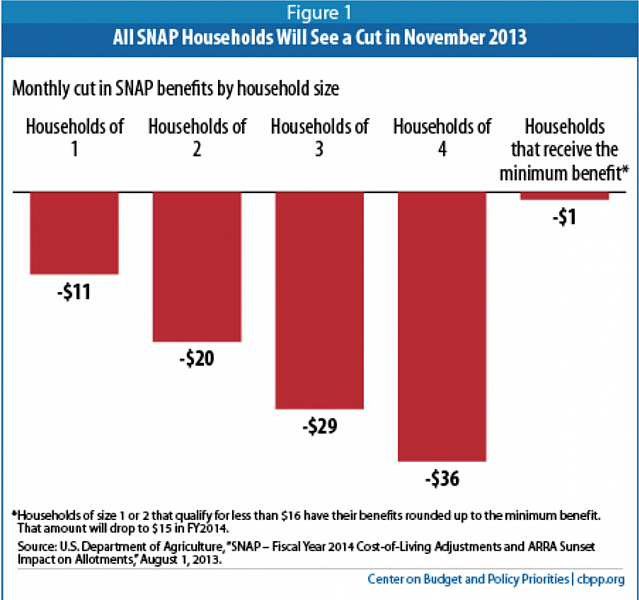

In the near term, SNAP households will have fewer dollars to buy food. A family of three now receives $29 less a month, a family of four $36 less a month. Lumped together, the average SNAP benefit is around $290 a month. SNAP now provides an average of $1.40 a meal per person, according to the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities. For a family of three, the cuts translate into a reduction of about 16 meals a month.

Such cuts to the decades-old safety, which used to be know as the Food Stamps program, are hitting several uniquely vulnerable groups: 22 million SNAP users are children and 9 million elderly rely on the program. Children, the elderly and the disabled make up two-thirds of all SNAP participants.

To qualify for SNAP, a household’s income must be at or below 130% of the federal poverty level. For a family of 3, that means an annual income of around $25,000 or less. Courtesy of the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities

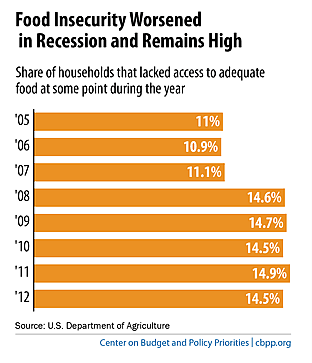

A significant portion of American households still struggle with food shortages, some occasionally others chronically. Nationally, almost 15% of households had trouble at some point during the year providing enough food in 2012, according to the USDA. Nearly 6% of households had “very low food security,” a more severe category that designates families in which food levels dip and eating patterns change.

While the cuts have only been in place for a month, news reports have already reported upticks in food pantry use and falling sales at stores that accept SNAP funds.

The most recent cuts were triggered by the sunsetting of stimulus dollars that increased SNAP benefits -- up to 13.6% more -- beginning in April 2009. The boost was designed to both stimulate the economy and address the soaring needs experienced by record numbers of families. (A report from Moody’s found that when it comes to stimulating the economy, SNAP dollars bring the best bang-for-your-buck, generating $1.73 for every dollar spent.) In 2007, there were 54 million Americans under the federal poverty level; five years later in 2012, that number had risen to 65 million.

As Republicans and Democrats negotiate over competing visions for the farm bill, potentially drastic changes to SNAP are under consideration by Congress. The Republican-led House plan would eliminate an estimated $39 billion over 10 years by making it harder to qualify for benefits. The Democrat-backed Senate plan would shave about $4 billion off the program. The Congressional Budget Office has estimated the House plan would deny benefits to 3.8 million low-income Americans in 2014 alone, with millions more bumped off in the years to follow.

Lambasting the potential cuts in a recent column, New York Times’ columnist Nicholas Kristof pointed to a study that found food stamps had a lasting, measurable impact on young lives:

An excellent study last year from the National Bureau of Economic Research followed up on the rollout of food stamps, county by county, between 1961 and 1975. It found that those who began receiving food stamps by the age of 5 had better health as adults. Women who as small children had benefited from food stamps were more likely to go farther in school, earn more money and stay off welfare.

More specifically, the study states that “access to food stamps in childhood leads to a significant reduction in the incidence of ‘metabolic syndrome’ (obesity, high blood pressure, and diabetes).”

The means by which food stamp benefits improve the long-term health a child are still being studied, but the study’s authors do point to an increase in nutrition during pregnancy and early childhood as especially important. They also suggest that reductions in pregnant mothers’ stress levels could positively change how babies are “programmed” or “imprinted” while in utero.

It seems unlikely such considerations will enter the current debate over the food stamps program. The near-term political haggling that will ultimately dictate the severity of SNAP cuts will likely soon be forgotten. The effects of those cuts on the health and well-being of young lives, however, could reverberate for decades to come.