How the Miami Herald told stories of lives caught in the ‘coverage gap,’ without falling into the politics trap

In some ways, it was easy to report our project, “Falling into the Coverage Gap,” because Florida and the Affordable Care Act have a love-hate relationship.

Though an estimated 1.4 million Floridians signed up for a subsidized health plan through the ACA’s Health Insurance Marketplace for 2015 – more than any other state – most of them are represented in the state Legislature and in the U.S. House of Representatives by Republicans who want to repeal the health law.

And while the state has one of the nation’s highest numbers of uninsured residents (about 3.9 million Floridians in 2013), an estimated 850,000 adults would be newly insured if Florida were to expand the eligibility criteria for Medicaid, the state-federal health insurance program for low-income, disabled and the elderly.

That’s just a fraction of Florida’s estimated uninsured population. But it’s a group whose lives are profoundly affected by public policy outside their control.

In Florida and the 19 other states that have not expanded their eligibility criteria for Medicaid, this group of people fall into what health policy analysts call the “coverage gap.’’

They don’t earn enough income to qualify for a premium tax credit that would make coverage more affordable under the health law, and they earn too much – or they’re just categorically exempt – from Medicaid.

Despite the numbers of Floridians stranded in this health policy no man’s land, the coverage gap was getting relatively little attention from both policymakers and local media. Instead, media covered the issue almost exclusively as a politics and policy story, which it was.

Despite the numbers of Floridians stranded in this health policy no man’s land, the coverage gap was getting relatively little attention from both policymakers and local media, including the Miami Herald, where I work.

Instead, media covered the issue almost exclusively as a politics and policy story, which it was.

The Florida Senate had adopted an expansion plan but the state House rejected it in unusual fashion: by abruptly ending the legislative session three days early.

The legislature later reconvened in special session to adopt a budget, but lawmakers never took up the question of Medicaid expansion.

But lost in the media reports — about the economic benefits that Florida was passing up by not expanding Medicaid, about the distrust state legislators have for the federal government, about the governor’s lawsuit alleging that the secretary of Health and Human Services was coercing Florida to expand Medicaid — were the voices of the low-income adults, many of them unable to work, who believed their lives would improve greatly with Medicaid.

It took a while to figure out how to approach and tackle such an enormous issue. But the story began to take shape about a month into reporting and talking with people and organizations working to help those in the coverage gap.

Among the first challenges was finding people in the gap who were willing to share their stories publicly, and who were facing an urgent medical need.

Because people typically do not find out that they fall into the gap until they apply for coverage through HealthCare.gov, I made contacts with navigators and others working to enroll eligible Americans for subsidized plans.

I also turned to old sources, such as Florida Legal Services, who had spoken to me in the past about their clients who were uninsured and unable to get care at public hospitals charged with providing them with medical services.

I contacted Florida International University to learn more about their mobile clinic program that provides free health care, counseling and other services to qualified low-income residents. And I reached out to nonprofits that help residents with health care needs, including Catalyst Miami, Florida CHAIN and the Health Foundation of South Florida.

I created a spreadsheet of people in the gap, and the more people I interviewed, the more it became apparent that they had powerful stories to tell.

In South Florida, home to the greatest number of uninsured residents in the state, I found people in the gap piecing together their own — largely inadequate — health care. They use free clinics, visit community health centers when they can afford the discounted prices and, if all else fails, wind up in a hospital emergency room that often leads to crushing debt.

They cut pills in half, borrow money or cash in retirement funds for co-payments, and wait months or even a year to see a doctor.

It’s an exhausting and haphazard way to get medical care, especially when people are at their most vulnerable — when they’re sick.

While these stories are powerful in themselves, they also needed the proper context. Medicaid expansion and the coverage gap can be difficult to explain and more difficult to write about in language that keeps readers engaged.

I also found that while the Affordable Care Act provokes strong feelings, many people still don’t understand how the law really works.

Many people I interviewed, including those who had fallen into the coverage gap themselves, blamed the Affordable Care Act for letting them down. They were angry and couldn’t understand why people who earned more than they did were receiving government subsidies for health insurance, but those with lower incomes received nothing at all.

Those who oppose expansion often resorted to tired stereotypes of able-bodied, single, low-income adults as somehow undeserving of Medicaid.

It helped to explain that the coverage gap was never supposed to exist under the Affordable Care Act, but that the Supreme Court’s 2012 ruling on the health law made Medicaid expansion optional, leading Florida and 19 other mostly Republican-led states to decide against it.

It helped to explain how the Medicaid expansion was supposed to bridge the gap between the poorest Americans and those who made enough to qualify for government subsidies.

It helped to repeat often for readers just how restrictive Florida’s Medicaid eligibility criteria is for low-income adults. Floridians cannot qualify – no matter how low their income is – unless they first meet certain categorical criteria, like being pregnant, disabled or a child under the age of 18. Parents of dependent children cannot qualify if they earn more than 35 percent of the federal poverty level, or about $5,500 a year for a family of two.

But those facts weren’t enough to drive home the point. I needed people to illustrate what the numbers were telling me.

In selecting candidates to profile, we wanted to show how the coverage gap affects a broad range of people: students with bright futures, middle-aged adults looking for new careers, single parents and childless adults, the working poor, and those who could no longer work because of health needs for which they could not find medical care.

As the Miami Herald’s health care reporter, and the person who pitched the story idea to the National Health Journalism Fellowship at USC, I took the lead on the project from idea development to execution. But in no way did I do this alone.

Together with my colleague Chabeli Herrera, we interviewed more than 50 people before the Herald ever published a story, including physicians who work with the uninsured, directors of federally qualified health centers, directors of free clinics, administrators at our local public hospitals, state representatives who support and who oppose Medicaid expansion, health policy experts from nonprofits like the Kaiser Family Foundation, the Urban Institute, the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, and others. We also reached out to national health care advocacy groups like Families USA and Enroll America, and to state consumer healthcare groups like Florida CHAIN.

Separately, WLRN radio reporter Wilson Sayre and I worked together to produce a series that focused on one woman’s experience in the coverage gap. We chose one person because of the medium: It was easier for listeners to follow one person’s story of life in the coverage gap.

In selecting candidates to profile, we wanted to show how the coverage gap affects a broad range of people: students with bright futures, middle-aged adults looking for new careers, single parents and childless adults, the working poor, and those who could no longer work because of health needs for which they could not find medical care.

We aimed for 10 profiles of people in the gap who were diverse in age, gender, race and ethnicity.

In addition to showing readers the challenges of living without health insurance, we wanted to explore the health care safety net that was supposed to help the region’s uninsured. We wanted to show how people with low incomes and few resources navigated a system of federally qualified health centers, free clinics, public hospitals, primary care centers and other resources.

We found that those who didn’t need the safety net were relieved that it existed. But those who relied on the safety net for their care were largely unhappy with the long waits to see specialists, copayments that even at $25 per doctor visit were unaffordable, and prescription drugs that were out of financial reach.

We also wanted to show that people fell into the coverage gap for a variety of reasons, sometimes through no fault of their own.

Personally, I wanted the public to read these stories and ask questions about the state’s refusal to expand Medicaid – not just about public financing and policy, but about the type of society they want to live in.

Did they want someone like Francesca Corr, a single mother of five and a paralegal who fell just a few thousand dollars short of qualifying for a premium tax credit to buy an ACA plan, to go uninsured? She’s the sole caretaker for her young children, who qualify for Medicaid.

Did they know someone like Edith Camacho, 52, and diagnosed with glaucoma? Camacho and her husband, Carlos, fell into the coverage gap after their lawn-mowing business earned about $4,000 less than it had the prior year. The drop in income meant the Camachos fell below the federal poverty level and out of reach of the subsidies they had received the prior year for health insurance.

Did it bother them that Cynthia Louis, 57, had worked most of her adult life at a Burger King and wanted desperately to work again but could not because she could not get in to see a rheumatologist to help get her back on her feet?

Or maybe they had someone in their family like Vincent Adderly, a diabetic man who can no longer walk the beat as a security guard because he gets lesions on his feet. When I first met Vincent in March, he was seeking care at hospital emergency rooms. I last wrote about Vincent in May, after his toe was amputated due to an infection.

Another challenge was coordinating a project that would incorporate two newspapers, the Miami Herald in English and el Nuevo Herald in Spanish, and a series of radio stories on Miami’s NPR station, WLRN, as well as an interactive map that would live online and hopefully act as a resource for those who need to find free or low-cost healthcare.

Did it bother them that Cynthia Louis, 57, had worked most of her adult life at a Burger King and wanted desperately to work again but could not because she could not get in to see a rheumatologist to help get her back on her feet?

It helped to include graphic designers, photographers, videographers, radio reporters and others in the early planning stages. But we also began talking about the series with community stakeholders – from legal aid groups to consumer advocates to health care providers – to get their input but also to begin setting the expectation that something big was coming.

The “Falling into the Gap” project was well received by the community. People who do not traditionally read the newspaper wrote to me after hearing our stories on the radio in South Florida, and when the story was picked up by radio stations elsewhere. Most recently, the radio stories aired on National Public Radio on July 11 and KAZU, an NPR station for Monterrey, Calif., on July 13.

One local nonprofit, the Health Foundation of South Florida, hosted a Medicaid expansion conference after our series published. “We did this because of your series,’’ the foundation’s vice president of communications told me when she invited me to speak on a panel that included state legislators and national healthcare experts.

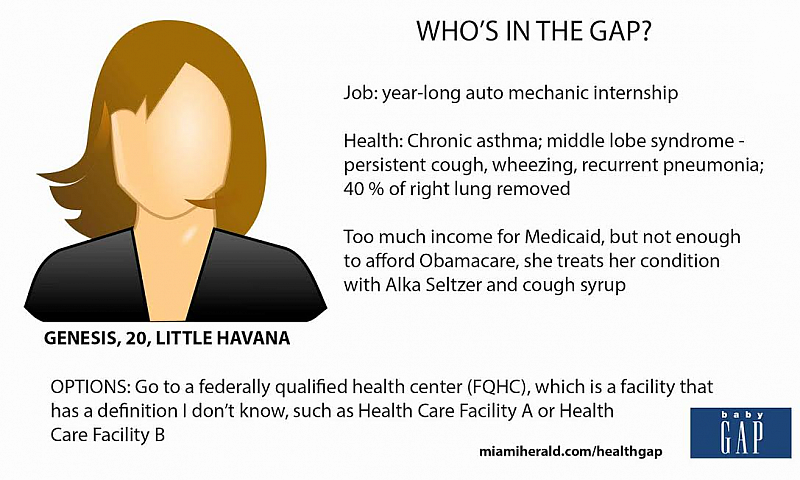

In order to begin preparing our audience for a package of stories on a complex health care policy issue they may or may not be familiar with, the Herald’s audience engagement editor, Megan Barrow, started sending out “cards” through the newspaper’s Facebook and Twitter accounts. The cards* were simple but catchy. They had a headline, “Who’s in the Gap?” and a picture of a person profiled in our series with a bit of information about them, like medical condition and the reason they’re in the gap.

These efforts paid off in social media, with Florida nonprofits Tweeting photos of the people we had profiled with links to their stories, and readers debating and sharing personal stories on the Herald's Facebook page.

The best part of all was probably also the most fortuitous. Our project published just as legislators in Tallahassee were in the heat of debate over whether to accept Medicaid expansion in Florida.

I don't know if our project changed any minds. That wasn’t really the goal. We had hoped to contribute to the public discussion about Medicaid expansion, and to remind readers and decision makers about the people most impacted by this policy question.

The following are links to Daniel Chang's series:

850,000 Floridians stuck in healthcare limbo — and no solution in sight

Relying on the healthcare safety net: choosing between dinner and a medical test

Medicaid is expanding in other states — just not Florida

[Photo by Jimmy Baikovicius via Flickr.]

* Sample card: