How two reporters became ‘armchair environmental scientists’ for series on toxic lead in Philly

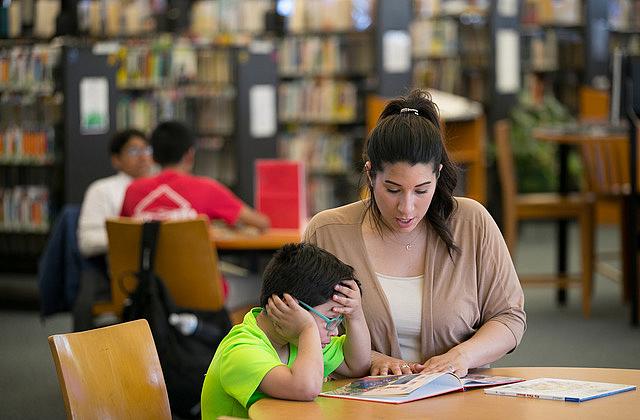

Cristine Pagan helps her son Dean with reading homework at a local library. When Dean started first grade at Comly Elementary last September, his classroom was filled with potentially hazardous deteriorating paint, and the school district knew it. (Photo Credit: Jessica Griffin/Philadelphia Inquirer)

When the water crisis in Flint, Michigan, erupted in 2015, we got to thinking: How many children are poisoned by lead here in Philadelphia?

Turned out, a lot. Each year, thousands of children are newly poisoned by lead — more than twice the national average and at rates far higher than in Flint.

We set out to learn why. The answer to that question took us on a three-year investigation that resulted in the Philadelphia Inquirer’s “Toxic City,” a five-part series in which we examined how the city’s children, many of them poor and minorities, are exposed to environmental hazards in their homes, backyards and schools.

The series was unique — and impactful — in part because we blended traditional street reporting with innovative scientific testing. When talking with fellow reporters about the project, they’re often curious about the testing, so we thought that providing additional details here would be useful.

Part One of the project, “Toxic City: Lead Paint,” published in October 2016, exposed how the city fails, year after year, to protect thousands of children from lead poisoning in old homes with deteriorating paint. The piece focused on how landlords repeatedly shrug off city laws aimed at preventing childhood lead poisoning. We told the story of Vaughn Jackson, who at age 2 got poisoned by lead paint in a rundown home his family rented from an out-of-state landlord who owned 52 other properties in the city. After Vaughn got sick, city health officials took the landlord to court and a judge ordered him to clean up lead hazards in the home. By September 2016, a new family was living in the home, which looked freshly painted inside. A lead inspector with the health department had declared the home lead safe. But we wanted to be sure. First, we asked the new occupants for permission to swipe test for lead. We had purchased several “lead check” swabs from Home Depot for about $10 apiece. After the swab turned red, indicating lead paint, we asked if we could return with a state-licensed, lead-risk assessor to test floors and window sills for lead dust. We hired a company called Criterion Laboratories in Bensalem, Pa., to do the testing. It cost us $375 for a “Lead Safe Inspection,” sample collection and laboratory analysis of eight dust wipes throughout the two-story, two-bedroom house. Turned out, four of eight areas tested for lead dust came back as hazardous. The test results, coupled with Vaughn’s medical records, provided readers with an unassailable account of how lead paint had a devastating health impact on a little boy and its toxic legacy puts future generations at risk.

Part Two of the project, “Toxic City: Tainted Soil,” published in June 2017, revealed how Philadelphia’s children were being poisoned by lead in soil in their parks, playgrounds and yards in the city’s river wards, a former industrial hub once home to 14 lead smelters. The story examined how a construction boom in the gentrifying area was churning up contaminated soil and spreading lead dust all over the neighborhood. Again, we hired Criterion Laboratories to help us test soil for lead. Our data reporter, Dylan Purcell, mapped the locations of all the old smelters and then we hit the streets, knocking on doors and asking residents if we could test their soil.

Initially, we went out with a state-licensed risk assessor who analyzed the soil samples in the field with a X-ray fluorescence spectrometer (XRF gun). During our Center for Health Journalism fellowship training, we had seen a demonstration of an XRF device during a tour of a neighborhood near the former Exide battery recycling center in east Los Angeles. But we quickly realized that going out with a XRF technician from Criterion was not practical for a number of reasons: First, we began reporting in early winter 2016 and the ground was frozen so the device took a long time to heat up the soil and measure lead concentrations. It was not only time-consuming but expensive. It cost $600 for an eight-hour day in the field and an additional $25 for each sample analyzed by XRF. (While out reporting, we also had the Criterion employee take dust-wipe samples of front steps and playground surfaces to test for lead dust from neighboring construction sites.) By day’s end, we were only able to test soil at about 14 locations, and we wanted to move more quickly, with ambitions to test hundreds of samples. So we called Criterion and asked two questions: Could we scoop our own soil and drop it off to be tested in the laboratory? And, could a Criterion staffer train us how to take dust-wipe samples and provide us with the equipment, including “Ghost Wipes” and sterile collection tubes? The answer to both was “yes.” We hit the streets with shovels, sandwich baggies, labels, and chain-of-custody logs to document location and date of sample. In all, we scooped some 500 bags of soil and took dust-wipe samples on playground surfaces before and after construction began at adjacent vacant lots (for $25 a sample). Nearly three out of four soil samples had hazardous levels of lead contamination. The testing also proved that construction crews were spreading lead dust during the digging of foundations.

By the time we got to Part Three of our project, “Toxic City: Sick Schools,” which ran over three installments in May 2018, we were ready to ramp up our testing. We knew we wanted to test for four health hazards in schools: Lead dust from chipping and peeling paint, lead in drinking water from old metal pipes, asbestos fibers from damaged pipe insulation and cracked floor tiles, and toxic black mold. (We also tested for silica in construction dust but that’s a long story). Problem was, we didn’t have access to school buildings. We decided to enlist school staffers and teachers to help us test. This proved to be the hardest and most ambitious part of our project. First, we needed to find a laboratory that did not have a conflict of interest and did not have an environmental contract with the School District of Philadelphia. Criterion was out for this reason. We selected International Asbestos Testing Laboratories in Mount Laurel, N.J., and met several times with scientists there to help us come up with a testing protocol that would translate to street-level reporting. We had already learned how to take dust-wipe samples for Part Two of our project; we just needed to train teachers how do it. We wrote up step-by-step instructions to test for lead, mold and asbestos and ordered scientific equipment online. We ordered 500 EPA-approved moist wipes for $1 apiece from Environmental Monitoring Systems and 500 collection vials (50 ml) for a total of $123.42 from Environmental Express. We made up “testing kits” and set about getting them into the hands of willing school staffers.

We cold-called hundreds of teachers, attended school events, union meetings and conferences. We contacted school staffers through direct message on social media. Many teachers were fearful of retribution, and it was slow going. We gave out hundreds of kits to staff who initially agreed to test but later went dark on us. It took roughly six months to recruit 26 reliable testers at 19 of the city’s most rundown elementary schools. We used public documents and internal school maintenance records to help teachers decide not only where to test, but what to test for. Some teachers took water samples from drinking fountains; others wiped surfaces to check for asbestos fibers or lead dust. Each wipe was only good for one test so if teachers wanted to test for both lead dust and asbestos fibers, we instructed them to take separate samples. As part of the verification process, we asked staffers to take photos of areas where they tested. The most expensive test by far was for asbestos fibers. We chose to use Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM), the most sophisticated laboratory method, at a cost of $85 per wipe for a five-day turnaround time. Lead wipes cost us $5.65 apiece for lab analysis, with mold “tape pull” tests at about the same price, and $15 for each water sample that we tested for lead. If your mind is not already exploding, you can get more information on how we did the testing here.

For all three parts of “Toxic City,” we spent $15,000 on scientific testing with our grant from the University of Southern California Center for Health Journalism, the Dennis A. Hunt Fund for Health Journalism, and the Lenfest Institute for Journalism.

When we began the series in 2016, we never imagined that we’d become armchair environmental scientists or that we’d deputized school staffers to help us test, but we’re glad we did.