The Million Dollar (Homeless) Patient

Angelo Solis is a chronic alcoholic in his late 60s who was homeless for many years in Solano County, California. Solis frequently passed out drunk in public, and police brought him to the hospital emergency room. There, doctors often admitted him to treat his multiple chronic health problems and so he could detoxify safely.

Solis would leave the hospital only to return after police found him passed out, again. This happened, repeatedly, for years. Solis' health never improved; it worsened because he slept outside and couldn't properly care for his diabetes or heart disease.

In three years, Solis racked up nearly $1 million in medical charges - paid for by taxpayers.

Solis' case represents the immense health care costs associated with homelessness. Nearly every community has at least one chronically homeless person like him. Some have hundreds.

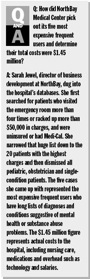

Hospital emergency room staffs call these patients frequent fliers. Many have chronic health problems worsened by living outside, in addition to substance abuse problems and untreated mental illness. Because their cases are so complicated they require expensive treatment and extra time from hospital staff.

But despite receiving repeated rounds of intensive and costly treatment, their health rarely improves when they return to the streets. They return to the hospital for more costly treatment again and again. Taxpayers and people with private insurance pay for this fruitless care, as hospitals shift costs onto them.

But despite receiving repeated rounds of intensive and costly treatment, their health rarely improves when they return to the streets. They return to the hospital for more costly treatment again and again. Taxpayers and people with private insurance pay for this fruitless care, as hospitals shift costs onto them.

That's the reason to convince your editor to write about the health care costs of homelessness in your community.

Here is some advice on where to start, who to talk to, and how to organize your time to report this story. I've also included relevant research, an expert list, and tips I wish someone had given me.

Planning

While conceiving the idea to write about the health care costs of the chronically homeless, two aspects of this problem interested me most. First, what happens when a homeless person is hospitalized and has no place to finish recuperating after being discharged? What does the hospital do? Where do they go?

Second, I wanted to quantify the medical costs for one homeless individual. Malcolm Gladwell's piece called "Million-Dollar Murray" in the New Yorker inspired my story on Solis. Focusing on the immense costs of one individual effectively demonstrated the magnitude of the problem.

The work for a project like this can be divided into two broad categories:

1. Finding the people

2. Getting the numbers

Finding people: Plant seeds early and be patient

Finding homeless people to illustrate these scenarios takes time – lots of it. But it is possible.

Start by getting to know the advocates who work with the homeless daily at shelters, the county programs, food banks, etc. While it's important to have a good relationship with the directors of these programs to guarantee good access, the caseworkers on the frontlines are your key to finding people. They know individuals and stories, and if they're good their clients trust them. If the caseworker trusts you, they can be immensely helpful. They are very busy people, however, so call them once a week to kindly remind them of your project.

Hospital social workers can also be great resources, but tend to be more cautious about helping because of HIPAA, the federal patient privacy law. Meet with them and the hospital public relations officials early to explain your project and get their buy-in.

Be patient. It may take several weeks or months before anyone turns up. Several leads may fail. Let go of them if they aren't right. Another will turn up. In the meantime, get informed. If you're like I was – filing a story nearly every day – set aside a one or two hours each week to find relevant studies and interview experts.

Getting the numbers

In addition to the peer-reviewed studies and abstract quotes from experts, you need solid, local data. Keep this in mind while searching for people to write about. You need them to be entirely transparent.

Calculating one homeless patient's health costs

You'll most likely have to get the patient's medical bills, records and other documents from the hospital or health plan (if they are enrolled in one). Relying on the hospital for billing records is tricky because patients can go to more than one hospital.

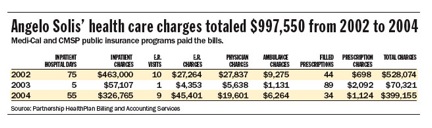

I lucked out here. Solis qualified for Social Security Disability Income and Medicaid. In Solano County, all Medicaid patients are enrolled in a managed care health plan. That meant all of Solis' medical claims were in one place. Solis signed a waver and the health plan produced his medical charges from 2002 to 2006. He had no charges after 2004, which is when he moved into the motel. Most California counties operate similarly so if you find patient enrolled Medi-Cal or even the county indigent program, it will be easier to get reliable numbers. (That is of course if the bureaucracy will help you.)

The following chart shows Solis' medical bills. While it says charges, the numbers indicate what the health plan actually paid. Be sure to differentiate between charges and paid claims or costs. Hospital charges or "sticker prices" do not reflect actual costs or payments.

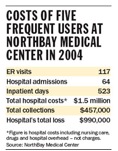

Calculating costs of frequent users

To demonstrate this was a broader problem, I asked one hospital to calculate the costs of its five most expensive frequent fliers. Admittedly, this was not a very scientific process. We agreed on a process to pick the five patients that satisfied us both. While I sat in the administrator's office, she searched the hospital's databases and looked for patients by how many times they came to the hospital, why they came and how much they cost to treat. She printed out the spreadsheets for me, and I could see that from January to December 2004, five individuals made 117 trips to the emergency room and spent 523 days in the hospital in the course of 64 admissions.

To demonstrate this was a broader problem, I asked one hospital to calculate the costs of its five most expensive frequent fliers. Admittedly, this was not a very scientific process. We agreed on a process to pick the five patients that satisfied us both. While I sat in the administrator's office, she searched the hospital's databases and looked for patients by how many times they came to the hospital, why they came and how much they cost to treat. She printed out the spreadsheets for me, and I could see that from January to December 2004, five individuals made 117 trips to the emergency room and spent 523 days in the hospital in the course of 64 admissions.

The administrator then worked with the hospital's financial and billing department to estimate the cost of care based on the diagnoses and length of stay to be $1.45 million. Again, be sure to differentiate between costs and charges. Hospital list prices or charges do not reflect the actual cost of treatment.

Offering solutions

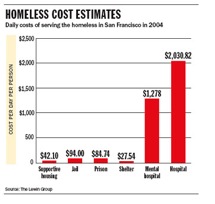

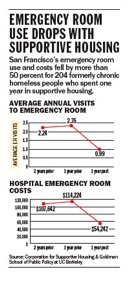

Many homeless advocates and medical experts point to supportive housing as a more cost-effective and humane solution to keeping chronically homeless people out of hospitals. Supportive housing combines affordable housing, case management and access to supportive services. Some programs don't require sobriety, and in response to criticism, they point to studies that show once housed, the addicts' costs to society greatly decrease.

Solis' case was a crude example of supportive housing. Solis lived in a dingy motel and a case manager checked on him regularly. While he didn't stop drinking entirely, he drank much less and didn't return to the hospital for two years after moving into the apartment.

Example of housing first

Example of housing first

The San Francisco Public Health Department dedicates $30 million of its $1-billion budget to housing 1,000 chronically homeless frequent fliers. A study by the program by the University of California Berkeley's Goldman School of Public Policy found that San Francisco's investment in supportive housing decreased hospital use of 235 formerly chronically homeless people by more than 50 percent.

Example of interim care

Another large problem is the high, unnecessary costs associated with homeless people who have no place to recuperate after a hospitalization. They either stay in the hospital longer at the price of at least $1,000 a day, or they return to the streets, where they fail to heal and often return to the hospital with the same problem, sometimes within days.

The Sacramento Salvation Army's Interim Care Program is an example of a program that provides a place for homeless people to stay in the short-term while they recuperate from a hospitalization. Local hospitals helped fund the interim shelter because they realized it would save them money by reducing the extra days homeless people spent in the hospital because they had no other place to go.

Things I wish I had known from the start

- Homeless people are hard to keep tabs on. Once you find someone willing to share his or her story, get information right away about their friends, where they live and hang out.

- A homeless person may agree to work with you, but may soon ask you for things in return. Be clear about expectations and demands up-front.

- Get a photographer involved early in the process, ideally from the first meeting.

- Think multimedia from the beginning! Bring your audio recorder to every interview. Practice using the video camera or request a photographer comfortable with video so you can include that Web element. Brainstorm ways to involve the readers in the story through online comments, listing ways people can help and including maps and user-friendly graphics.

- Without nagging, keep in close touch with the caseworkers and hospital social workers helping you find patients. Otherwise, they will forget about you.

- Don't give yourself or your editors a deadline. You can't determine the timeline for this type of project. It took me seven months to complete.

Research

A landmark study led by Dennis Culhane at the University of Pennsylvania greatly shifted the federal government's philosophy on homelessness. There has been an increasing push to focus on the small number of people who consume the majority of resources. Culhane's study estimated that in 1999, chronically homeless people with several mental illnesses in New York City used about $40,000 per person in public services, such as emergency shelters, police, jail, mental health crisis centers and hospitals.

Health costs of the chronically homeless

Dr. James Dunford led a study in San Diego that followed 529 homeless, chronic alcoholics from 2000 to 2003. The results showed those people were transported by ambulance 2,335 times, amassed 3,318 emergency room visits, and required 652 hospital admissions, resulting in 3,361 inpatient days. Their health care charges totaled $17.7 million.

Academic studies

- Dunford, James. et al. "Impact of the San Diego Serial Inebriate Program on Use of Emergency Medical Resources." Annals of Emergency Medicine, April, 2006.

- Greene, Jan. "Serial inebriate programs: what to do about homeless alcoholics in the emergency department." Editorial. Annals of Emergency Medicine. June 2007.

- Thornquist, Lisa, et al. "Health care utilization of chronic inebriates." Academic Emergency Medicine. June 2002. (Minnesota)

- Salit, Sharon, et al. "Hospitalization costs association with homelessness in New York City. New England Journal of Medicine. June 11, 1998.

Health status of the homeless:

The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services' Homeless Programs Branch has research on the health problems common to many homeless people. A 1999 survey found that two in three homeless people had substance abuse and mental health problems; 3 percent had HIV or AIDS; one in four had acute medical problems including tuberculosis and pneumonia; and nearly half had chronic health conditions such as high blood pressure, diabetes or cancer. www.hhs.gov/homeless/research/index.html

The price of hospital services:

I went to the U.S. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality to find an average cost of an emergency room visit and doctor's visit.

Efficacy of supportive housing

Lewin Group. "Costs of Serving Homeless Individuals in nine cities." Nov. 19, 2004.

Culhane, Dennis, et al. "The Impact of Supportive Housing for Homeless People with Severe Mental Illness on the Utilization of the Public Health, Corrections, and Emergency Shelter Systems: The New York-New York Initiative." May 2001.

Other Reporting Resources

Corporation for Supportive Housing, an Oakland-based nonprofit that works with governments to build supportive housing. Will provide experts for interviews.

HomeBase, The Center for Common Concerns, a San Francisco-based advocacy law firm works with governments at all levels to create 10-year plans to end chronic homelessness.

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services' Homeless Programs Branch

U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, homelessness division

National Alliance to End Homelessness, has several fact sheets and can provide experts for interviews

National Law Center on Homelessness and Poverty, also will provide experts for interviews and legal analysis.

Partnership to End Long-Term Homelessness, has a section listing case studies. You may be able to find one in your area.