NYT’s Andrea Elliott shares what Dasani’s story and immersive journalism can teach us

Andrea Elliott, an investigative reporter for The New York Times, has a seemingly limitless ability to gain access to the most intimate moments of other people’s lives. Her reporting feats are made all the more impressive when you consider that the people she writes about — poor, battling homelessness and addiction, constantly surveilled by child welfare agencies — have every reason to distrust a stranger like her.

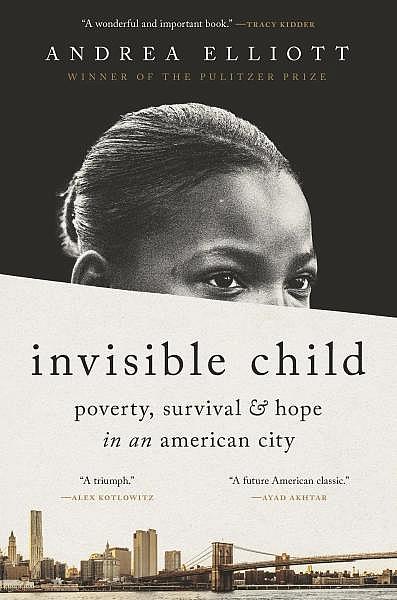

Elliott’s 2013 “Invisible Child” series for The New York Times tells the story of then 11-year-old Dasani and her large family as they endure chronic poverty and homelessness. One of the most remarkable aspects of the reporting is how Elliott manages to capture the range of moments she does — from candid phone calls between a mother and daughter to the very instant the family is torn asunder by New York City’s child welfare system. Somehow, she seems to be always there, blended into the scene, quietly documenting. They’re the kind of moments available only to a reporter who goes all in, fully immersing herself over months or years in the lives of those she’s writing about.

That reporting journey began in 2012, when many Americans were still struggling to recover from the Great Recession, and the Occupy Wall Street movement had just drawn fresh attention to economic inequality. Elliott recalls her sense that the dimming of the American Dream has created a growing audience for a story that looked at the age-old problem of poverty in new ways. With much of the conversation focused on adults, the response to stories of poverty tended to fall into predictable traps of “worthy” versus “unworthy” poor. Elliott’s editors at the Times worried her stories on these themes would be swallowed up by victim blaming and political noise, she said.

A striking statistic eventually led her to an end-run around the problem: One in five children in the U.S. were living in poverty, largely unnoticed, rarely heard from, never voting. They were inherently sympathetic: No one could possibly blame them for their plight. She told her wary editors she should just write about kids.

But finding the right child to focus on was challenging. “They tend to live, wherever they are, in marginalized communities, and as a matter of survival they do all they can to hide their poverty and to protect their parents from the intrusion of outsiders,” Elliott said. “They are very carefully surveilled by government agencies, and so basically we're talking about a very hard target,” she said. “And experience has shown to me that the best match for a hard target is deeply immersive reporting.”

But immersion depends on finding the right target first. She talked to experts early on, seeking to grasp the face of child poverty in 2012. That led her to create a highly detailed checklist of various qualities a representative family might have. The search continued. One story lead would have forced her to travel repeatedly to Michigan, a distance she deemed too great to practice the kind of daily immersion she was seeking. In the end, she jettisoned the checklist and focused on searching among the 22,000 homeless children that call New York City home, since that’s where she lives.

It proved a smart move, since she would’ve never found Dasani through that checklist. According to experts, the face of child poverty would likely be Hispanic or mixed race, from a smaller family hovering right on the poverty line. Dasani was one one of eight kids, living with parents who struggled with addiction, chronic unemployment and homelessness. As Elliott would later describe their living conditions, “All 10 of them — Dasani, her parents, her seven siblings and her pet turtle — were living in a single mouse-infested room at Auburn Family Residence, a decrepit city-run homeless shelter just blocks from townhouses that sold for millions.”

Dasani and her family exerted an undeniable pull on Elliott. “That (Dasani) could articulate what she was experiencing in a really profound and moving way is what mattered to me, more than anything,” Elliot said. “That she wanted to narrate her own experience … She had just such a presence, such a spark, such a sense of herself, as the oldest kid and as one is who is really the third parent in the home and a leader.”

Elliott started putting in the hours. She gave Dasani’s mother, Chanel, a recorder to capture the family’s daily high and lows around the dinner table. Elliott filled stacks of notebooks, racked up 132 hours of audio on her live-scribe pen, and gathered nearly 30 hours of video. Times photographer Ruth Fremson often accompanied her; at one point the pair snuck into the shelter through a fire escape and past inattentive security guards to document the awful conditions the family was living in, from shredded mattresses to a mop bucket doubling as a urinal so the family could bypass the dangers lurking in the communal restroom.

The bedrock on which her reporting style rests is being there, bearing witness to scenes and experiences in people’s lives, in all their immediacy and complexity. It’s easy to say, hard to do, especially day after day after day. “I believe you have to be there enough to write it like you know it,” Elliott said.

The commitment to being there also helped Elliott build trust and familiarity with Dasani and her family.

“I think it's just about spending time with them, showing with your time, with your body, with your presence, your interest is worth more than anything you can say. And I think what worked the most with Dasani’s family was the fact that I just kept showing up,” Elliott said. “I could talk my best game, but it wasn't worth a fraction of what my presence was worth. What that showed them was, Here I am, and I’m not going away. I’m coming back, day after day after day.”

Her constant presence in the family’s lives made traditional precepts on journalists' personal relationships with sources seem unhelpful or antiquated. Elliott ended up sleeping on the family’s floor at times, taking them out for meals, offering rides, sharing stories of her own family’s tragic loss. Guardrails for this kind of reporting are often inadequate. She found The New York Times guidebook on “Ethical Journalism” woefully out of touch on such matters, pointing to “Mad Men” era language on source relationships such as: “A City Hall reporter who enjoys a weekly round of golf with a City Council member, for example, risks creating an appearance of coziness, even if they sometimes discuss business on the course.”

Elliott found better insights into these sorts of ethical tangles in the work of academic ethnographers, where the “asymmetry of power” between the interviewer and the source is explicitly acknowledged and theorized. “You have more power than they have, by virtue of the fact that you are in charge of how the story is going to be told — and also because of things like social capital and the world you represent versus the world they represent,” she said.

For Elliott, the power gap inherent in this kind of reporting is less an ethical dilemma to be solved than lived with. “The price we pay, I think, is to wrestle with that always and to never take it for granted, and to never really be too comfortable with it.”

**