Black advocates fight for justice in foster care

The story was originally published by the Observer with support from our 2025 Child Welfare Impact Reporting Fund.

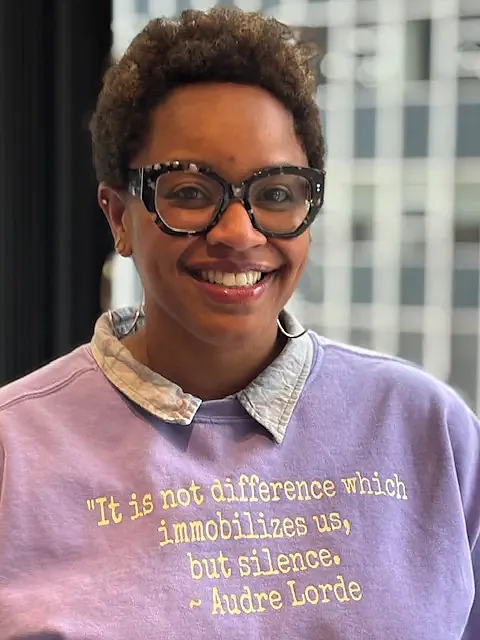

Former social worker Tandrea Thysell still sees system-impacted youth in her current role as a therapist. She’s also a foster parent.

Louis Bryant III, OBSERVER

Given how it has historically shown up in the African American community, the child welfare system has earned its critics. They point to a history of systemic racism and inequality that leads to a disproportionate number of Black children being removed from their homes and spending more time in foster care than children of other ethnicities. Some of the most outspoken detractors are former social workers, legal experts and adults who have been scarred by their experiences in the system.

A number of African Americans are working from different vantage points to address the disparities and improve the level of care that Black children receive

Tandrea Thysell

When Tandrea Thysell learned that one of the teens in her CPS caseload had taken her own life, she had mixed emotions.

“It broke my heart that she killed herself, but I also thought, ‘She’s finally safe.’ That’s a shame, but it’s the truth,” said Thysell, a clinician who previously worked for Child Protective Services (CPS) in Contra Costa and San Joaquin counties.

The girl had been molested multiple times, starting in her birth home.

The abuse continued after she was placed into foster care and later adopted. She ran away from her adoptive home where she was being groomed and was sexually assaulted again. After returning, the abuse by her adoptive father continued.

The National Human Trafficking Hotline identified approximately 16,500 potential trafficking victims in 2021. Because of the clandestine nature of the crime, detecting and identifying an exact number of victims is difficult. Vulnerable groups such as current or former foster youth are frequently targeted due to adverse childhood experiences (ACEs), trauma, runaway history, mental health challenges, or lack of support.

The National Foster Youth Institute estimates 60% of child sex trafficking victims have been in the child welfare system. Sacramento has a high prevalence, with a study estimating more than 13,000 potential victims from 2015-2020. Many of these are Black youth, adding to their “invisibility,” says activist Leia Schenk, who supports them through Project T.A.K.E.

Advocates such as Schenk and Thysell don’t sugarcoat the realities many foster youth experience daily.

“You’re a grown-ass man having sex with your barely teenaged adopted daughter,” Thysell says of the teen she hoped to find stability for. “No part of this sh*t is OK.”

Placed in a children’s shelter, the teen ran away and the “father” continued to have sex with her. CPS moved the girl to Southern California to put some distance between her and her abuser. Instead of solace and a fresh start, she found drugs and more trauma.

“We moved her down there and she got C-SEC’ed by one of the counselors there.”

“C-Sec” is short for “commercially sex trafficked” or “commercially sexually exploited children.”

“This is all by the time this girl was 14 years old. Every adult who was sent in her life, who should have protected her, failed miserably.”

The system is broken, Thysell says, with parts that should be dismantled entirely.

Tandrea Thysell and her husband Steve have dedicated space for the foster children they’ve welcomed into their homes and hearts.

Louis Bryant III, OBSERVER

“We need to do better,” she says. “The system recognizes that they suck at raising children, which is why they have foster homes, but then they make it so hard to become a foster parent.”

Thysell knows because she and her husband have been foster parents for the past decade. They initially planned to adopt, but as an interracial couple shifted their attention to fostering after encountering the complexities and racial dynamics involved.

Thysell’s work as a former social worker has helped guide them over the years.

“If I wasn’t a social worker, I wouldn’t know how to move within the system. It has benefited me as a foster parent, for sure, and even as a therapist, because when my families come to me saying they don’t know what to do, I tell them, ‘I can help you figure this out. Let me help you navigate this,’” she says. “I know how to get a kid help. I know how to advocate to get the services that this kid is going to need.”

As a therapist, Thysell sees foster children regularly. Many of them are Black, being fostered by whites.

“It’s usually because there are behavioral issues with the kids,” she says. “There’s a lot of trauma and the older the child, the more they remember, and it’s also how long that they’ve been in the dysfunctional situation. That affects their views, how they deal, how they see the world, and of course, depending on their trauma and their experience, that also impacts their behaviors.”

Kids who have had sexual trauma can act out sexually as well.

“You run the risk of them possibly molesting or inappropriately touching another child,” Thysell says. “There are concerns with that, or them even trying to push up on grown men or women because they don’t understand boundaries and they don’t understand that that’s inappropriate. They didn’t exactly learn that, and sexual trauma may have been why they were removed from the home.”

Many foster parents are unaware of a child’s past experiences until the child begins to display these behaviors.

“There’s only so much information that you’re given when you take on a foster kid, and sometimes that’s information that even the social workers don’t know,” Thysell says.

Before transitioning to being a clinician, Thysell’s cases took her throughout the country, including local trips to the Sacramento Children’s Home, where some of “[her] babies” were placed.

“You go wherever your kids are,” she says of the work.

Social workers’ hands often are tied by rules and policies that don’t actually serve children’s or families’ best interests, she says.

“I didn’t go by every rule they set because if it didn’t make sense, I wasn’t doing it,” Thysell says. “But I looked out for my kids and I looked out for my families.”

When Thysell walked away from CPS after five years, it was with no regrets.

“I did my job.”

Kim Pearson

The local CPS falls under the umbrella of the county’s Department of Child, Family, and Adult Services. Kim Pearson is addressing disparities as a division manager.

Roberta Alvarado, OBSERVER

As a division manager in Sacramento County’s Department of Child, Family, and Adult Services, Kim Pearson has been in a position to directly impact tangible change.

The county has reduced its overall foster care population by 26.5% over the last five years. There has been a 31.5% reduction in Black children in foster care during this same period.

In 2017, Pearson had the county implement a Cultural Broker Program, which a retired Black social worker, Margaret Jackson, started in Fresno. Cultural brokers are culturally competent liaisons who act as buffers between system-impacted families and social workers. Locally, the program has been credited with significantly reducing the number of Black children in CPS care. Maintaining partnerships with other county agencies and related organizations has also proven fruitful, Pearson says.

“We know that every jurisdiction has overrepresentation and disparities within their system, and we also know that it’s not even just limited to child welfare,” she adds. “It’s the juvenile justice system, it’s the adult system, it’s the school system. We could have just landed there and said, ‘Well, that’s just the way it is,’ but that’s not who we are. We wanted to do something about this.”

There has been increased focus on kinship care, implicit bias for social workers and other mandated reporters, and safe sleep baby training done in collaboration with the Child Abuse Prevention Council.

“The focus on child safety is just not CPS alone,” Pearson says. “We have to engage and we have to partner in a way that is inclusive and invites others in, to be able to be part of that systemic change.”

Representation has to matter, she continues, but having the county willing to listen and invest in efforts to address disparities is critical.

She admits to being accused of “crossing over to the other side” by people who view her working for CPS as being OK with the system’s beleaguered history. She’s not.

“I’ve always been true to who I am, to my background,” Pearson says. “We look at data to drive where we need to go, and then you have to have that representation to lift up the culturally responsive supports and services that are needed within a community.”

For her, moving the needle is worth some of the negativity that might come with the job.

“We choose to invest our dollars in really bringing forth some systemic change, so that we show up differently. That helps to then chip away and starts to erode some of those larger systems,” she says.

Shereen A. White

As director of advocacy and policy for the New York-based Children’s Rights organization, Shereen A. White has garnered national and international attention for child welfare accountability in the Black community.

Shereen A. White joined Children’s Rights in 2019 as a senior staff attorney. The national advocacy organization’s policy work focuses on racial inequities in child welfare. In 2021, White took on the role as the organization’s first director of advocacy and policy. She could have gone into a more financially lucrative area of law, but a personal connection to the child welfare system put her on a different career path.

“People are hurting and struggling and until they’re not, we have to keep pushing,” says White, a graduate of both Duke University and the Villanova University Charles Widger School of Law. “I want to be able to use the privileges that I’ve had and this education that I’ve had to do good for children and families that look like my own.”

White’s father aged out of the New Jersey foster system.

“I grew up with him telling me stories about what that experience was like and the abuse he endured in foster homes,” she shares.

White’s father was separated from his parents and five sisters in foster care, only staying with his two brothers. White knows firsthand the lasting, multigenerational effects of family separation.

White’s father’s experience in long-term foster care deeply influenced his parenting. He distrusted the system immensely and frequently warned his children to “not tell their business” to outsiders.

In her current role, White has helped successfully petition two U.N. treaty bodies to hold the U.S. accountable for the unjust policing and separation of Black families by the U.S. child welfare system. Her father’s experiences help shape her drive.

“I hold that in this work,” White says. “I feel like a lot of my work is to try to help make sure that families don’t experience what his did.”

Dr. Angelo A. Williams

Dr. Angelo A. Williams says it’s past time for reform that addresses the overrepresentation of Blacks in the child welfare system. Dr. Williams tackles the issue in his work as chief deputy director of First 5 Sacramento.

OBSERVER File Photo

When it comes to child welfare reform, Dr. Angelo Williams taps into the wisdom of the ages.

“My strategy is always Malcolm and Martin, a little bit of Assata [Shakur], a little bit of Angela Davis, and a little bit of Ida B. Wells,” says Dr. Williams, the former chief deputy director of First 5 California.

The overrepresentation of Black children in the system, he adds, demands stakeholders put aside old affiliations and old ways of thinking.

“The day has come for Black people to use all strategies,” Dr. Williams says. “We’ve got to have people in the system reforming the system. We’ve got to have people outside the system attempting to transform it and change it. We’ve got to have people who are working on both sides, inside and outside, talking directly to the people because gone are the days where people can just pimp the Black problem. We can’t have that any more.”

In California, the infant mortality rate for Black infants is more than twice that of white infants, irrespective of education and income levels. Studies suggest these perinatal outcomes stem from toxic stress accumulated over a lifetime due to racism, alongside biases from health care providers and racial inequalities in health care quality and accessibility.

Dr. Williams engaged partners collectively around responses to the harmful impact of adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) and toxic stress.

“What we’re trying to do, first and foremost, is to get everybody on the same page. That’s the way we’re trying to change the system,” he says.

First 5 offers a number of in-home programs including Healthy Families America, Nurse Family Partnership and Parents as Teachers to support families who are expecting or have recently had a baby, emphasizing maternal health, child development and stability.

“Home visiting is probably the single most important investment that we actually have made over time,” Dr. Williams says. “All of these programs are in-home support to parents who are at risk of losing custody of their children due to child welfare involvement.”

Professionals are trained in parent education, child development, support, screening for maternal depression, domestic violence, and substance abuse. They also connect families to housing, health care and employment resources.

“The beauty of the home-visiting programs is that there’s a ton of research that’s been done over the last 20 years that shows that home visiting significantly reduces child maltreatment, particularly those cases that are hard to get to,” Dr. Williams says.

He calls those that conduct the visits “systems navigators.”

“When you say ‘home visiting,’ particularly for our folks, it’s, ‘You ain’t coming to my house.’”

Building trust is key to the change the community wants to see.

“They want to know about the welfare of the child,” Dr. Williams says of these navigators. “Yes, they want to know about their food and nutrition and all the rest of it. Yes, they want to know about their doctor’s visits and all the rest of that, but they’re not there to check up on people. It’s not the FBI or the CIA. These are people who have resources, most of them rooted in community, but then, based upon what people say, navigate them through systems. That is extremely important when it comes to child welfare.”

Creating trust isn’t easy. Theirs is a nonjudgemental approach, but child safety is paramount, Dr. Williams says.

“I’m trying to bring Black folks’ pressure down. Nobody’s coming to check up on you like that, but you can’t abuse your children.”

Dr. Williams stressed the importance of centering the voices of parents and caregivers and using that firsthand knowledge to modify the system. Many prefer to begin with theories, he continues, but when solutions are implemented, those affected often find them inadequate.

“It sounds good,” he says, “but what are we going to do about our kids?”

Malachi Chaney-McClain

Malachi Chaney-McClain’s story is one of resilience, growth and the transformative power of stability. He shares his experiences in the child welfare system to help foster change.

Roberta Alvarado, OBSERVER

Malachi Chaney-McClain doesn’t have to see the logo on the door to recognize a county vehicle.

“My sister and I still look for them. Even though we’re grown, we’ll see cars around town and be like, ‘Oh, that’s CPS, that’s a social worker,’” he says.

Chaney-McClain remembers countless rides in such vehicles. Rides that took them away from parents who were dealing with drug addiction, underdiagnosed mental illness and frequent incarceration. Occasionally the children were placed with relatives, but other times they were sent to live with strangers.

Though he’s 24 now, the fear and anxiety associated with CPS is still palpable for Chaney-McClain.

He shares his lived experience as a member of the California Youth Connection, a youth-run group focused on developing leaders and advocating for changes to the foster care system through lawmaking and policy reform. He also wants to help others navigate the system’s complexities.

“Oftentimes our voices are silenced, overlooked or dismissed. At times our words are even misconstrued and [we’re often] traumatized in the stages of life where we need the most support,” he says.

Chaney-McClain has felt the generational impact of trauma and foster care.

“My mom was battling addiction. She was assaulted as a child. She was also in foster care,” he says. “My father was not in foster care. His family was able to get him, but he bounced around from family member to family member until he was 17.”

The children frequently shifted between their parents and their respective partners, living in vacant apartments where they had to “borrow” electricity, at other times staying in motels or being homeless. When they did have a legit apartment, Chaney-McClain purposefully took the bed near a window.

“If CPS came, I wanted to be able to jump out the window,” he recounts. “It was on the second floor and there were bushes. I wanted to be able to catch my sisters and to just not be taken anymore.”

The family tried to stay off CPS’s radar, but sometimes school staff reported them and at other times domestic disputes led to police involvement. Chaney-McClain recalls staying at a motel with his father and his girlfriend, who were on methamphetamines, and being awakened in the middle of the night by a police officer shining a light in the children’s faces. While in foster care, Chaney-McClain was faced with an impossible choice. There wasn’t a home large enough to take all the siblings and as the oldest, a social worker made Chaney-McClain choose who went where. Considering ages and temperaments, the 11-year-old made a hard decision.

“There was a house that could take two of us and there was a house that could take three,” he recalls.

It was a lot of responsibility, and pain, for a child.

“When we were separated, I didn’t know where they were,” Chaney-McClain says.

Some of the siblings, it turns out, were just 10 minutes away, having also been placed in a foster home in the Florin area.

“We found each other at the park one day, both of our foster parents just dropped us off with their kids,” he says.

Their parents’ rights were terminated a year later when Chaney-McClain was 12.

Despite enduring cycles of hardship, a beacon of hope emerged in the form of his “nana,” who formally adopted them and allowed him to be a child for once.

“I raised my four sisters. I was grown in my head,” he says. “But at 13, my nana, she told me, ‘Let me be the parent and you be the kid.’”

Chaney-McClain would find warmth and acceptance in his transition from female to male at age 15.

“She’s my hero, she’s everything,” Chaney-McClain says. “She’s the reason I’m here today. I don’t know where I’d be, who I’d be, or if I’d be without her.”

Nana’s encouragement was instrumental in shifting Chaney-McClain’s perspective and aspirations, but the constant upheaval he’d experienced left its mark.

He tried his first edible at age 17, then smoked marijuana a year later. He was on prescription medication for anxiety and depression and later “turned to Xanax” in college.

“I didn’t want to feel and think about anything,” he admits.

Instability has resurfaced while he has attended Sacramento State. He chose the local university for its proximity to home and because it provides free tuition and other resources to former foster youth through its Guardian Scholars Program.

Former foster youth Malachi Chaney-McClain, 24, credits his grandmother, Mary Chaney, left, the California Youth Commission and Sacramento State’s Guardian Scholars Program with his personal growth.

Roberta Alvarado, OBSERVER

The National Institutes of Health report that youth in foster care are more likely to experience mental health issues, such as PTSD, reactive attachment disorder, anxiety, and depression. Research also indicates a heightened risk of substance abuse among former foster youth. These findings, along with data on homelessness, exploitation, and mental health crises after foster care, highlight the pressing need for improved support.

“Supporting foster youth after age 18 is really important,” Chaney-McClain says.

He has worked as a behavioral aide for neurodivergent youth and others who need academic support and had an off-campus apartment, but experienced homelessness once again after some financial issues. He turned to escorting to make money. Sex work can be particularly dangerous for trans men like Chaney-McClain.

“I ended up being drugged and I had an anxiety attack. It was very bad and I tried to take my life.”

That was May 25, 2024. A year later, Chaney-McClain is turning pain into purpose, working with California Youth Connection and speaking before area lawmakers.

“I’m grateful to have people who are letting me into rooms where I can tell them, ‘This is what happened to my family and this is why this is important.’”

Advocacy by former foster youth has led to critical legislation across the country. Advocates helped Congress pass the Fostering Connections to Success and Increasing Adoption Act in 2008, which provides states the option of extending foster care to age 21. California is one of 28 states that do so.

In May, Assembly Bill 562, also known as the Justice through Placing Foster Children With Families Act, passed the California Assembly and was sent to the Senate. The bill aims to address the disproportionate number of Black and Native American children in foster care and prioritize family placements for them.

“I don’t think that would have been possible without the CYC,” Chaney-McClain says.

Chaney-McClain’s graduation from college in spring 2026 will demonstrate his resilience and inspire others to rise above the hands they’ve been dealt.

“About 3% to 4% of foster youth go on and obtain a college degree,” he says. “When I walk that stage, it’s going to be because someone believed in me enough to let me try.”