Prosecuting drug-dependent pregnant women and new moms hurts families

Photo: Mario Tama/Getty Images

Stigmatizing and punishing pregnant women and new mothers for having drug dependency problems is not a new concept in the United States. Since 1973, women have been prosecuted for illicit drug use during pregnancy in at least 45 states. According to the National Advocates for Pregnant Women, more than 800 women have been jailed for drug dependency issues in the last decade alone.

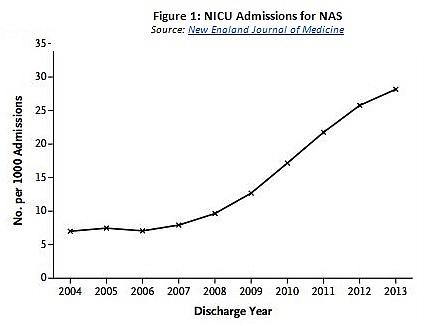

These indictments are part of a broader national initiative to curb opioid use and reduce the rate of infants born with neonatal abstinence syndrome (NAS). NAS is a drug-withdrawal syndrome that most commonly occurs after a baby is exposed to opioids in the womb. The number of babies born with NAS in the United States has been on the rise in recent years, with one study reporting that the rate of neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) admissions for newborns with the condition increased from seven cases per 1,000 admissions in 2004 to 27 cases per 1,000 admissions in 2013 (see Figure 1). Prenatal care has been proven to greatly reduce the negative effects of substance use during pregnancy for both mom and baby. However, pregnant women with substance use disorders may be dissuaded from seeking care for fear of the potential legal consequences.

(Click to enlarge.)

As of January 2016, three states have criminalized illicit substance use during pregnancy. These include Tennessee, whose law recently expired, as well as Alabama and South Carolina, where high courts have interpreted existing statutes to allow for the prosecution of pregnant women and new mothers. Substance use during pregnancy is considered an act of child abuse in 18 states. In three states, drug use during pregnancy is grounds for involuntary civil commitment to a treatment center. In addition, 15 states have laws requiring health care workers to report suspected drug use by a pregnant woman to local authorities, and four states require hospitals to perform a drug test if drug use during pregnancy is suspected (for a complete survey of state laws related to criminalizing drug use during pregnancy, visit ProPublica’s interactive map).

This breadth of state laws, though ostensibly designed to curb addiction and produce healthy infants, actually result in poorer health outcomes, according to the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG):

Incarceration and the threat of incarceration have proved to be ineffective in reducing the incidence of alcohol or drug abuse. Legally mandated testing and reporting puts the therapeutic relationship between the obstetrician–gynecologist and the patient at risk, potentially placing the physician in an adversarial relationship with the patient.

ACOG adds that “drug enforcement policies that deter women from seeking prenatal care are contrary to the welfare of the mother and fetus.”

Not everyone bears the brunt of these policies equally. The criminalization of pregnant women with substance use disorders is a social justice issue that disproportionately impacts low-income women and women of color. Though no research indicates higher rates of substance use during pregnancy for black women versus non-black women, black women and their babies are more than 1.5 times more likely to be drug tested in a hospital setting than non-black women, and 10 times more likely to be reported to public health officials.

One study found that other factors besides race can also contribute to the likelihood that a pregnant woman or new mom is tested for illicit drug use, including lower socioeconomic status, being unmarried, having less than a high school education, being unemployed, and having Medicaid or no insurance coverage at all.

To improve birth outcomes for moms and babies, states should ensure that needed services and supports are available to women with substance use disorders. This can be accomplished, in part, by removing the stigma of substance use during pregnancy and reducing racial and socioeconomic biases in the health care system.

Likewise, media outlets should raise awareness of proper screening and treatment options for women with substance use disorders, and journalists in particular should focus on sharing personal stories to demonstrate that these laws are doing more harm than help. Pressure from the media, health advocates, the provider community and others are at least partially responsible for the sunset of the controversial Tennessee law, the first of its kind to explicitly make it a crime to use drugs while pregnant. Negative media attention, coupled with the fact that fewer women were accessing prenatal care as a direct result of the legislation, resulted in the bill expiring on July 1.

Will Alabama and South Carolina follow suit to ensure that no other pregnant women or new moms are convicted? It’s a story worth tracking.

Emily Eckert works for the Association of Maternal and Child Health Programs, where her she focuses on improving continuity of coverage and care for pregnant women and children.