Report: Where You Live Shapes Kids’ Care

Map courtesy of the Dartmouth Atlas Project

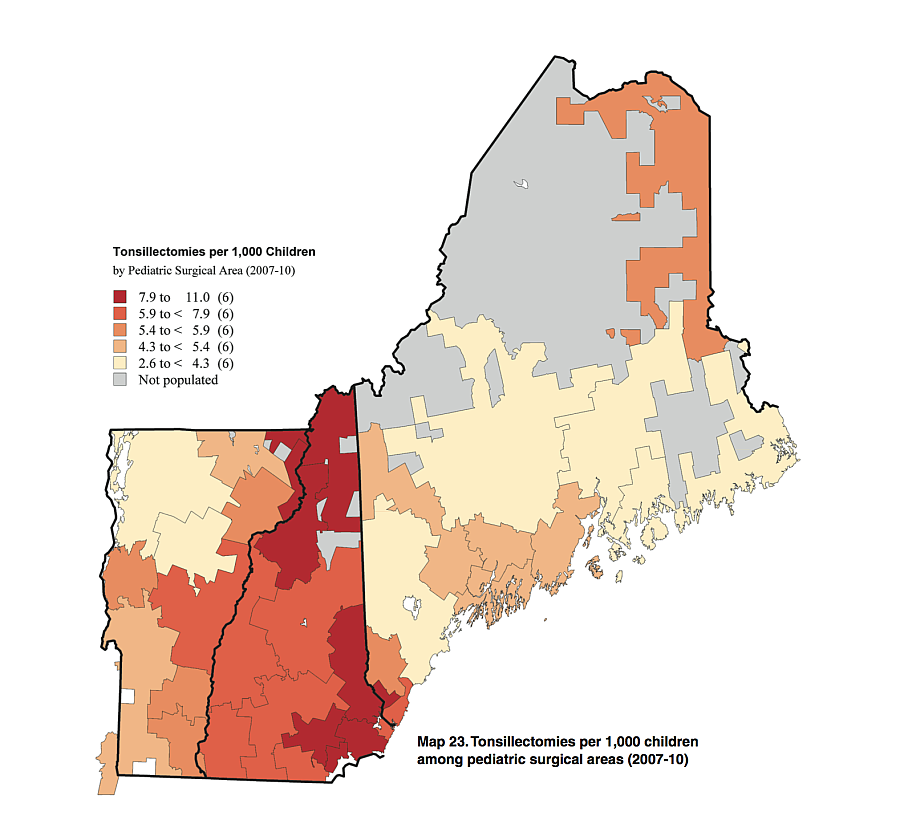

Has your child has his tonsils removed or head scanned lately? Whether or not you said yes may have something to do with where you call home. A new report released last week by the Dartmouth Atlas Project finds that, in the states of northern New England at least, where a child lives influences the kind of care that child receives.

Some of the differences are dramatic: Children living in Manchester, N.H., are three times more likely to have their tonsils removed than children in Bangor, Maine. Kids in Dover, N.H. had nearly twice as many E.R. visits as their peers in Burlington, Vt. A child in Burlington, Vt., is about half as likely to receive a CT scan of their head as a kid in Lewiston, Maine.

“Whether the care is lead screening, tonsillectomies, mental health hospital admissions, or prescriptions for psychotropic medications, health care depends a great deal on where children live and receive their care,” the report concludes.

All that variation raises some red flags, according to the authors, as it suggests that too often factors other than the patient’s condition is determining what tests are ordered, which surgeries are performed, or if follow-up appointments are made or not. The report draws its conclusions from a vast database of claims records for children under 18 in Vermont, New Hampshire and Maine from 2007 to 2010, with both private insurers and Medicaid included.

“While there are many examples of excellent care for children, the inconsistency in care across a relatively small geographic region raises troubling questions about whether medical practice patterns reflect the care that infants and children need and that their families want or whether they are primarily the result of differences in physician and hospital practice styles,” said Dr. David Goodman, a professor pediatrics at Dartmouth Geisel School of Medicine and lead author of the report, in a news release.

The study confirms findings from an earlier dataset amassed in the 1970s, when some of the same researchers found that in the town of Morrisville, Vermont, 60% of children had their tonsils removed by age 15, while in other communities the figure was around 20%.

A few more striking differences found in the new report:

- In Newport, Vt., 70% of children prescribed medication for ADHD had a recommended follow-up appointment within 30 days, compared to 35% in Lewiston, Maine.

- In St. Albans and Bennington, Vt., children had more than three times as many office visits (3.6 visits a year) compared to kids in Dover-Foxcroft and Houlton, Maine (1.3 and 1.2, respectively).

- In Nashua, N.H., 90% of kids were appropriately tested and given antibiotics for strep throat. In Houlton, Maine, that figure dipped to 47%.

- In New Hampshire, children in Rochester, Derry and Concord were about twice as likely to receive chest X-rays compared to kids in Littleton and Peterborough.

“This suggests that there is a significant amount of overuse of medical services in some areas," Dr. Vikas Saini, a cardiologist and president of the Lown Institute, told Reuters in response to the report as a whole. “Especially because unneeded care can expose children to harmful side effects, this is very troubling.”

So what’s driving all this variation in the relatively small, homogenous confines of northern New England? One might expect that socioeconomic differences or other characteristics of the populations in these three states would account for the variations in care. But the Dartmouth researchers, who controlled for such variables, say that’s largely not the case. “The variations, instead, are primarily the result of differences in the way physicians, hospitals, and clinics provide care,” they write.

One area may have more physicians than another area. Some hospitals may have invested more in CT scanners than others. Physicians may practice differently depending on where they trained or the local medical cultures in which they practice. More hospitals beds can lead to more beds being filled. Parents’ (or physicians’) preferences might be heeded on procedures lacking clear benefits. The report says there’s no single driver explaining the variation:

The patterns of pediatric care observed across the regions of Northern New England are the sum of thousands of well-intentioned decisions by doctors and nurses, but they do not all represent “best care.”

But good data is the first step in identifying inconsistencies and questionable practices. As it stands right now, there is far more public reporting and measures of care on the elderly than children, according to the report: “Nationally, children’s health care is a black box.”

One way to pry open that black box is through the adoption of “all-payer claims databases,” which a minority of states have begun to make available. These types of databases combine claims records from private insurers and Medicaid for nearly all patients, giving researchers a better understanding of how health care is being delivered to a whole population by a range of providers.

Only a handful of states have such databases up and running, but expanding their use across the U.S. could give researchers and medical providers a much more fine-grained sense of how care is being delivered to kids and where “best practices” have yet to arrive.

Until then, location, location, location will likely keep looming larger than it should in determining whether any given kid gets that strep test, CT scan, or tonsillectomy.

Related Stories:

Leading Early Childhood Expert Seeks Missing Breakthroughs