Tap these FDA recall reports to find the dangers lurking inside our own bodies

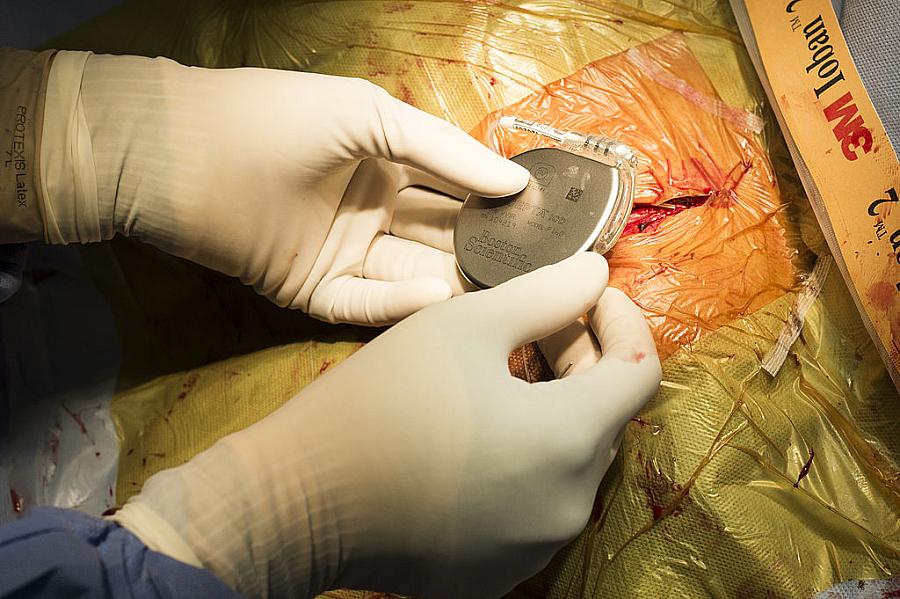

(Photo: Fred Dufour/AFP via Getty Images)

Early in the pandemic, I received a recall notice on my car. The dealership had closed down temporarily, and so I wasn’t able to go into the shop to get it fixed, making me worry that something would go very wrong if we ever were to get back on the road. (We’ve cancelled all of our big trips.)

How much more fear, anxiety, and personal risk would I be experiencing if the part that was being recalled wasn’t inside my car but was inside me?

Millions of people have undergone procedures that require the implanting of a medical device: To fix bones and joints, to help hearts function properly, to aid in the self-administration of medicine.

Those devices undergo recalls, just like car parts.

And recalls have been on the rise. You can see this for yourself in the data tracked by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration. There is a wealth of information on medical devices, even if that information is spread out over several departments within the agency. Here’s a quick tutorial to help get you started on some stories.

A good first start would be to familiarize yourself with what is happening with medical device regulations broadly. Implants fall inside medical devices in terms of regulation. There are myriad reports out there about medical devices, largely aimed at people trying to gain market intelligence for investments. One source that has been used for academic research purposes is Stericycle Expert Solutions, an outgrowth of the hazardous waste management company that makes those little red boxes in your doctor’s office for disposing of hypodermic needles. The company advises other companies on risk management and safety, and it produces a quarterly report on medical device recalls that has been used by researchers to understand trends in the industry. You can download their reports by providing a few of your personal details. (When you are filling out the form required to download a report, the company asks for your industry but does not provide “media” as an option, and so I just chose “indirect,” feeling fairly certain that I am indirectly connected to any number of industries on the list.)

The report includes broad context such as:

As medical device companies work to meet the increased demand for critical equipment and personal protection products caused by the COVID-19 pandemic, they find themselves operating in what may be the industry’s most challenging business and regulatory environment in recent history.

And it contains a lot of specifics, including trends that you can track the same way researchers have. For instance, it shows that medical device recalls were up by 31% in the second quarter of 2020, leading Stericycle to predict that there would be 1,200 recalls by the end of the year.

Now, back to the FDA.

The agency’s information on devices and recalls can be found in multiple places:

1) First, there is a summary of the FDA’s Medical Device Recalls program. Here you’ll find links to the high-level list of the current year’s recalls plus previous years. It can be a little confusing because you will see recall counts in the Stericycle reports and other analyses that don’t seem to match the list here. That’s because this is a list of recall announcements. And the announcements often cover multiple types of devices. For example, a May 2020 recall of an Endologix stent covered multiple models. The FDA’s announcements provide great explanations of the problems with the devices and the impacts on health. They also often include diagrams or three-dimensional renderings. Here’s what the FDA wrote about the stent:

By issuing the recall on May 6, 2020, Endologix is clarifying that the root cause for most polymer leaks is a material weakness caused during the manufacturing process. The weakened area may gap or open during use, which can cause liquid polymer to leak outside of the device as it is filled. If there is not enough liquid polymer in the device to seal the aneurysm, blood may continue to flow into the aneurysm, requiring additional procedures to properly seal off the aneurysm. Liquid polymer may leak into the patient’s body. This may cause serious health consequences, including severe allergic type reactions, unstable blood pressure, tissue damage (necrosis), organ failure, cardiac arrest, central nervous system problems, and death.

2) Then there is MedWatch. This is the FDA’s Safety Information and Adverse Event Reporting Program. This program covers devices and a lot of other areas, including medicines, nutritional products, cosmetics, food, and other products. The agency takes in reports from the public, health care providers, and the device makers themselves. When it decides the evidence merits it, the agency issues an announcement and lists them on the MedWatch site. If you already are tracking a story because of a recall, this can be a place for you to gather additional information, context, and the all-important paper trail. Again, going back to the Endologix stent recall. In June 2020, a month after the recall, the company announced that it had issued something that journalist are familiar with: a correction, which in this case meant it had found the root cause of the problems with one of its devices, namely, “a material weakness.” It also noted that the number of patients that had experienced an adverse event — including strokes, liver failure, and rashes — related to the stent had gone up from 47 out of 7,285 (or 0.65%) to 112 out of 12,763 (or 0.88%).

3) Lastly, the FDA maintains the database with the greatest name in the history of federal government databases: MAUDE. It stands for the Manufacturer and User Device Experience, and it captures “medical device reports submitted to the FDA by mandatory reporters (manufacturers, importers and device user facilities) and voluntary reporters such as health care professionals, patients and consumers.”

You can search by body part (heart) or device type (stent) or company (Endologix). I tried a bunch of different searches just to see what would come up. To stick with the theme, though, I decided to see how far back I could go in finding problems with Endologix. I did a search for the earliest year available, 2010, and the company name. It came up with 152 results, way more than I expected. I started to go through them from the earliest to the most recent. The first report was from Jan. 7, 2020. It described a patient whose life was put in danger in October 2009 — there are always reporting lags — because of some combination of the device and the person inserting the device into a patient, although the company’s report put the emphasis on the doctor, calling it “improper or incorrect procedure or method.” The patient suffered “hemorrhage/bleeding,” “vessel perforation,” and a “pseudoaneurysm,” which is what happens when blood leaks out of a vessel into the surrounding tissue.

The patient survived, but patient after patient continued to show up in reports about the same product over the course of the year. One patient died, although the report notes that the exact cause of death was unknown. A few weeks later, another report called out the death of a patient. A deeper review of the themes in these reports, both from 2010 and then in more recent years, could be the seeds of an interesting investigative story, particularly if matched with the recall reports and lawsuits.

So, when you next receive your own recall notice on your vehicle – because they just seem unavoidable – think about the recalls that signal even more serious problems. Not in our garages, but inside our cardiovascular systems, our bones, and our organs.