Telling stories about the underserved amid health reform’s changing landscape

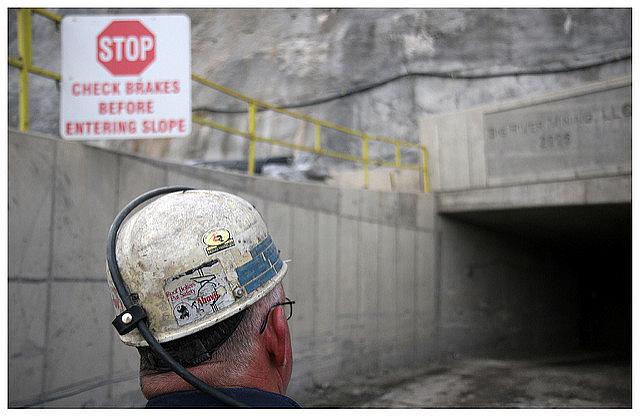

Laura Ungar has reported many stories on health reform’s rollout from Appalachia, where a diminishing coal industry has left many on hard times.

Now that we’re a few years into the Obamacare rollout, how are efforts to lower the number of uninsured residents working out in California, long considered a bellwether for health reform?

“The number of uninsured has decreased by almost 50 percent in the last two to three years, which is a big, big, big deal,” said Richard Figueroa, director of health and human services for The California Endowment.

That may be a big deal, but as Monday’s 2016 California Fellowship panel on the plight of California’s underserved made clear, there’s still a way to go if universal coverage is the goal. Of California’s nearly 3 million remaining uninsured, about two-thirds are Latino, and half are undocumented.

Insurance costs and undocumented status are two of the biggest barriers to reaching more Californians, a state that will expand Medicaid to low-income undocumented children starting this May. The “family glitch” and out-of-pocket costs hit underserved groups hardest as well, Figueroa said. But a growing economy has allowed many counties to strengthen their safety net services, and the recently approved Medicaid 1115 waiver should increase funds for county services for the uninsured as well, Figueroa said.

New ways of delivering care

One of the signal challenges of providing care for all these newly insured Californians is an ongoing shortage of primary care doctors, a problem made worse by the state’s bottom-of-the-barrel reimbursement rates for Medicaid patients.

But newer health care models seek to address the shortage in part by embracing a team-based approach to care. The starting lineup will vary, but you might have a nurse case manager, social worker, health educator, physical therapist, specialist and primary care doctor all working together to manage a patient’s care.

“It doesn’t always have to be a primary care doctor for all these things,” said Dr. Michael Hochman, director of the Gehr Family Center for Implementation Science at USC Keck School of Medicine. For instance, it often makes more sense for a nurse to make sure all immunizations are up to date, and a health educator might be able to keep a patient’s diabetes under control far more cheaply and effectively than periodic doctor visits alone.

In his previous role as director of innovation at AltaMed Health Services in Los Angeles, Hochman teamed with USC’s School of Pharmacy to bring pharmacists on to the patient team, where they help patients manage complex medication regimens, tailor dosages, make follow-up calls, even make home visits to identify hidden problems. (I’ve written previously about the program here.)

While a primary care doctor might have needed to see a patient a half dozen times to bring their diabetes under control before, the pharmacist on the team can do much of that same work instead, freeing up the primary care doctor to address other pressing health concerns when the patient does come in.

“We learned that pharmacists are trained to do a lot more than they’re typically allowed to do in retail pharmacies,” said Hochman, who supports a system in which “everyone practices at the top of their license.”

According to the data collected, the pharmacists did a better job at managing patients' diabetes than the doctors did, with a corresponding reduction in ER and hospital use. (That doesn’t necessarily mean the program saves money overall; Hochman said the pharmacy program makes more sense in capitated rather than fee-for-service payment systems, given the current billing structure.)

Telling peoples’ stories

More people are gaining coverage, and health care providers are perpetually experimenting with new care models. But are these changes making a measurable difference in real peoples lives yet?

Two health care reporters who have done laudable work in answering that question were on hand Monday to recount their experiences: Laura Ungar of the Louisville Courier-Journal and USA Today, and Tracy Seipel of the San Jose Mercury News.

Ungar’s recipe for combatting “health care ennui” (“Another wonky Medicaid story?!”) also serves as sound Journalism 101 for making any policy story come to life: “I think the way I’ve kept it alive for editors is to talk about what it means on a personal basis,” Ungar said. “I’m always thinking about what your reader would want to know. How would you bring it alive for people?”

For Seipel, that has included stories that take a hard look at the challenges faced by new enrollees in California’s Medi-Cal program, which now covers one-third of the state’s residents. “The new enrollees, in particular, are having a very tough time getting services,” she told fellows, citing unanswered phone calls, long wait times for care, a scathing state audit and ample patient complaints.

“It’s kind of a mess out there, and I think that’s something California reporters in particularly should be looking into, which is how well are they really managing this huge influx of Medi-Cal?” Seipel said. “And for all the money they’re throwing at Covered California, where’s the beef? Why aren’t we seeing a little more traction?”

Ungar, whose beat includes rural Appalachian areas of Kentucky and Tennessee, says doctors have told her that they’re being inundated with new Medicaid patients, many with serious, complex health conditions. Since Medicaid rates tend to be lower than private insurers', it’s had the effect of driving down physicians’ incomes, even as the level of patient difficulty rises. “They’re getting paid less to do more basically, and I hear that again and again from doctors,” Ungar said.

Both journalists offered tips for how reporters can find people who can breathe life into what can otherwise wither into dry policy briefings.

“A lot of folks I have found through various social service agencies, or social activists,” Ungar said. For example, the uninsured Tennessee farmer who can’t afford a prosthetic limb and suffers horrible chest pain came to her via a well-connected former-nun-turned-social-activist.

“Another really good source in Texas was the food pantry, because they put you in touch with folks who are struggling in various ways,” Ungar said. “Where might the type of person you’re writing about hang out? Start with that, and then who can help you get in touch with those people? Churches, religious groups, nonprofits.”

Added Seipel: “The people who are trying to help the people who need help are the folks you should go to.”

They also mentioned chatting up insurance agents and small business owners, using Facebook and other social media channels, crafting a callout, or going old school and putting an ad in the paper describing the type of people you’re seeking.

“One of the women that I found who was on Medi-Cal had been diagnosed with uterine cancer,” Seipel recounted. “It took, no kidding, six months from the time she had blood in her urine to the time she had her surgery. That’s not good.”

“She was found through a fetcher in the newspaper,” Seipel added. “That’s a great way to find people.”

[Photo by Philippe Roos via Flickr.]