Will California’s move to abolish cash bail spur jail reforms in Texas?

At the end of August, California Gov. Jerry Brown signed a bill abolishing California’s cash bail system as we know it.

Across the country, politicians, public officials, criminal justice reform advocates and the bail industry are now waiting to see what happens next.

After years of criminal justice reforms aimed at federal and state prisons and long-term incarceration, attention shifted in recent years to pre-trial incarceration: Local jails where people are locked up after an arrest.

Nationally, data show that the volume of people held in local jails has ballooned, and the length of their stays has increased substantially in many places. This is due to many state systems’ heavy reliance on cash bail, regardless of a defendant’s ability to pay.

The result has been hundreds of thousands of people locked up each year, who have not yet been convicted and are constitutionally entitled to be released before trial.

Traditionally, bail has been used simply to ensure that people who are accused of crimes turn up for their court dates. But in many jurisdictions, it became the default, rather than the exception, to set bail without examining whether a defendant had the means to pay, was a dangerous threat or was likely to miss court hearings.

Experts say the system is particularly tough on women, who usually make less money than men and account for a sharply rising number of inmates. Sometimes, their children may be left to fend for themselves while mom is locked up, a problem I investigated for The Dallas Morning News and the USC Center for Health Journalism's Fund for Journalism on Child Well-being in 2017.

Critics of the current cash bail system say jailing people like this often costs them jobs, custody of their children and safe housing. It can even affect the outcome of their criminal cases (studies show incarcerated people may be more likely to accept guilty pleas, simply to get out of jail).

In New York City, police have the discretion to issue "desk appearance tickets” for offenses such as marijuana possession, driving with a suspended license and petty theft. Florida also allows police to opt for civil citations for certain types of crimes instead of making arrests.

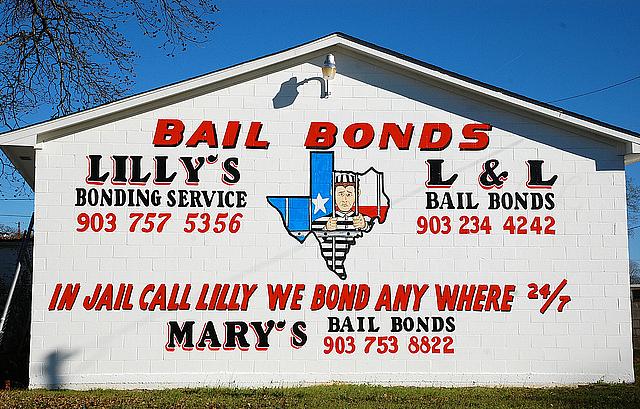

But California’s new law has plenty of critics: Including bail bondsmen, who say it will put them out of business.

Surprisingly, some of the critics now are groups who originally supported the idea of the bail reform law, such as the ACLU of California. As passed, they argue, the new law doesn’t do enough to protect citizens’ due process rights or to guard against racial biases and disparities.

Though California’s law virtually eliminates cash payments as a condition of release, a last-minute change created a facet of the law that some feel gives judges too much power to keep people in jail under an option called “preventative detention.”

Prosecutors can seek this option for certain offenders, until a judge determines at a hearing if an inmate is a risk to public safety or unlikely to show up to court. Allowing judges such greater discretion will likely lead to more inmates locked up, not fewer, the ACLU argues.

In Dallas County, where I met and reported about the case of Angela Jessie in 2016, judges effectively already had an option akin to this: a personal recognizance bond. But most rarely used it, data showed, and cash bail was the default — not an exception.

Jessie’s bond was initially set at $150,000. She was granted a personal recognizance bond more than two months after she was locked up, when The Dallas Morning News requested to photograph her inside the county jail. Her story prompted promises from officials to reform the system so taxpayers wouldn’t continue paying thousands of dollars to incarcerate a grandmother who stole $105 worth of school uniforms.

Where reforms have languished in Texas and the U.S., civil rights groups have tried an alternative strategy: Suing on behalf of indigent defendants in federal civil rights lawsuits that argue cash bail is a “wealth-based detention scheme.” Rich people who may be dangerous are allowed to purchase pre-trial freedom, when many nonviolent offenders sit in jail simply because they’re poor, the lawsuits argue.

These groups scored a victory in Houston, largely upheld by the Fifth U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals, but county officials are still fighting the outcome. Lawsuits in Dallas and Galveston counties are ongoing.

State officials in Texas say they’re striving for some sort of happy medium: keeping cash bail as an option, but adding risk assessment tools so nonviolent offenders who don’t pose a safety risk can be released quicker.

Yet risk assessment tools have plenty of detractors who allege some of the more commonly used ones may have inherent racial or gender biases.

Meanwhile, social justice groups suing several counties in Texas over the cash bail issue say officials have promised change but kept the system working as usual.

Attorneys for the plaintiffs in the lawsuit against Dallas County recently released video from bail hearings inside the jail showing some of the hearings lasted only 15 seconds, and never inquired about a defendant’s ability to pay.

[Photo by Steve Snodgrass via Flickr.]