Youth e-cigarette use continues to rise. Will the vaping crisis reverse that trend?

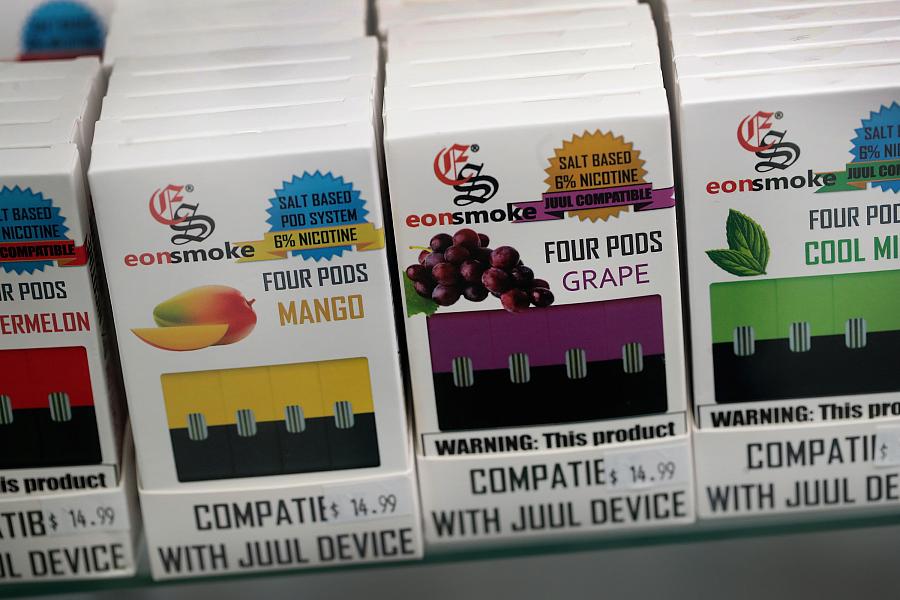

“Without flavors like mango or mint, I think most teens would lose interest in vaping and not continue after an initial try,” researcher Richard Miech said. Above, vaping products on sale in Chicago, Illinois.

(Photo by Scott Olson/Getty Images)

For the past few years, American kids’ e-cigarette use has exploded.

The nicotine vaping rate among eighth, 10th and 12th graders more than doubled from 2017 to 2019, according to numbers published recently in the New England Journal of Medicine.

“The increase in nicotine vaping ... from 2017 to 2018 was the largest increase we've ever seen for any substance we've ever measured in the 44 consecutive years of our national survey — and we track dozens of substances,” said Richard Miech, a co-investigator of the Monitoring the Future youth substance-use study at the University of Michigan.

“I did not think that such a torrid pace could continue into 2019, but it did,” he added.

But will the outbreak of vaping-related lung illnesses, in which 19 people have died and more than 1,000 have fallen ill, help curb that trend? That crisis has left federal, state and local regulators scrambling to limit and better monitor the sales of e-cigarettes.

“I think we’re hitting around peak e-cigarette rate,” said Kurt Ribisl, chair and professor in the department of health behavior at the Gillings School of Global Public Health at the University of North Carolina. “We’re finally getting the attention of the policy makers that will rein in the behavior of the vaping companies.”

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration is moving to ban flavored e-cigarette products, as Michigan, New York, Rhode Island and Los Angeles County already have. Massachusetts has temporarily forbidden all vaping products, and San Francisco has banned e-cigarette sales.

“We ask students why they vape, and the second most common reason is because they like the flavors (the most common response is curiosity/experimentation),” Miech noted. “Without flavors like mango or mint, I think most teens would lose interest in vaping and not continue after an initial try. And some teens wouldn't try at all if their friends who had vaped told them it was a gross experience.”

Some public health experts, however, believe this is the wrong approach, particularly since THC products may be playing a bigger role in the vaping-related illnesses than nicotine.

“I think these bans are going to make the outbreak much worse,” said Dr. Michael Siegel, a professor of community health sciences at Boston University. “I think we have enough experience from the past to know that prohibition doesn’t work, and prohibition opens up black markets with even worse products that maybe weren’t foreseen.”

He said that the conflation of nicotine and THC vaping by public health officials is deceptive, and that they may see the current crisis as an opportunity to scare people away from all vape products.

“The problem in public health is we view the ends as justifying the means,” he said. “We have to be honest. As an ethical code of public health, we have to be ethical in our communications.”

He said he believes the bans could also push kids back to using traditional cigarettes — which have been long thought to be more harmful than the electronic variety — and that the smarter approach would be to more tightly regulate e-cigarettes, including raising the purchase age to 21.

Other policy solutions include requiring warning labels on the health risks and shutting down online vendors that sell to children, Ribisl said.

E-cigarettes have often been touted as a less-damaging alternative to combustible cigarettes, which are said to kill more than 480,000 Americans a year, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

“The goal of policy … is to prevent youth from picking up e-cigarettes without stopping adult smokers from switching to e-cigarettes,” said Jessica Barrington-Trimis, an assistant professor of preventive medicine at the Keck School of Medicine of USC.

However, she said preliminary research she is involved with, as well as some older data, show that e-cigarettes are attracting kids to nicotine at a higher rate than when tobacco cigarettes were the only option.

Part of the reason for that, she and other experts believe, is the new pod-based vaping products, popularized by the company Juul, that deliver nicotine more effectively and at higher levels than past versions, thus potentially making them more addictive.

Juul’s emergence has coincided with the recent spike in youth e-cigarette use — it now controls roughly two-thirds of the market — and the company has come under intense scrutiny for its marketing practices.

“I think 10 years ago, nobody would have predicted that e-cigarettes would have become as popular as they are,” Barrington-Trimis said. “Even five years ago, nobody would have predicted the direction they’ve gone in.”

**