At 99, Ronghui Ye Enjoys Life in Subsidized Senior Housing. She is Lucky. Others Wait Decades for Housing They Can Afford

The story was co-published with World Journal as part of the 2025 Ethnic Media Collaborative, Healing California.

Known to friends as “the roly-poly grandma,” Ronghui Ye shows little sign of her ninety-nine years. Jian Zhao for World Journal

In a subsidized senior apartment in eastern Los Angeles County, 99-year-old Ronghui Ye tends to her small vegetable garden every morning, watering sweet potato leaves and red amaranth — greens beloved in many Chinese kitchens.

Known to friends as “the roly-poly grandma,” Ye shows little sign of her ninety-nine years. She has no chronic illnesses, no hypertension, and remains lively and quick to laugh as she recalls her long life.

“If I weren’t in America,” she says, “I don’t think my health would be this good.”

Ye immigrated from China, in 1997 to reunite with her son’s family after decades apart. Now she lives independently in a one-bedroom apartment, paying just over $270 a month thanks to government rent assistance.

Public-health experts have long agreed that stable housing is one of the strongest predictors of health. When older adults have a safe, affordable place to live, hospital visits drop, mental health improves, and health-care systems save billions of dollars.

A 2024 national review found that older residents in quality affordable housing experienced a 27% reduction in hospital admissions and inpatient days and median health care costs (per person per month) after 12 months of permanent housing that were approximately one-fourth of those in the year prior to having housing.

“Housing is health care”, as Justice in Aging emphasizes.

A Patchwork of Public Programs

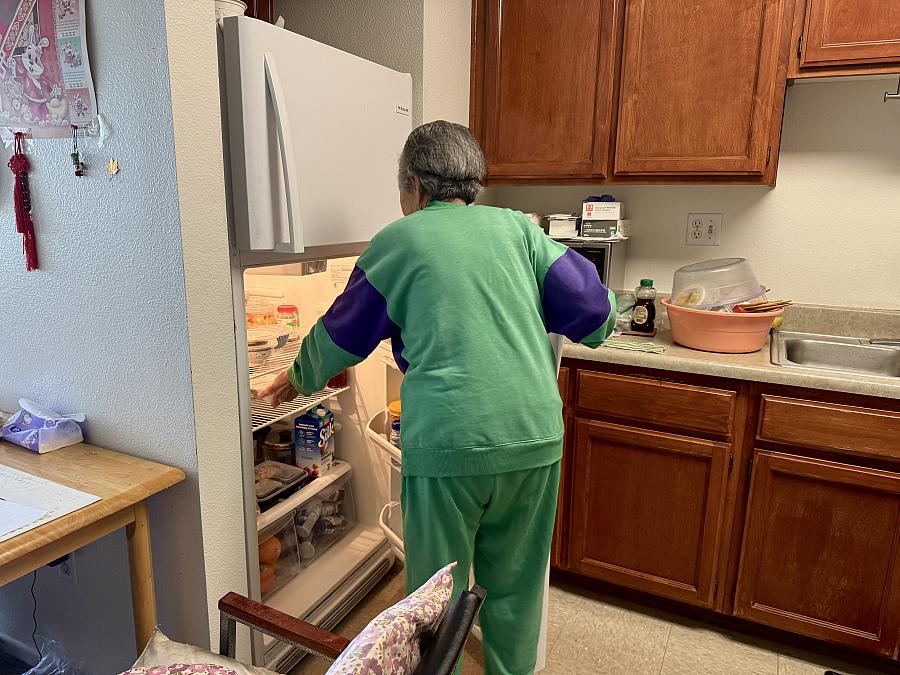

Ye’s days follow a quiet rhythm sustained by a patchwork of public programs built around her housing stability.

Ye cut sweet potato leaves for her kitchen. Jian Zhao/World Journal

Her home is part of a senior housing complex subsidized by the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) under the federal Section 8 program, which provides long-term rental assistance for low-income families. Residents who live in these units pay about 30% of their income in rent.

Ye moved in 2000, after winning a lucky draw — a system now replaced by long waiting lists.

“I was really fortunate,” she says. “Some people are waiting more than a decade.”

Because demand far exceeds supply, most affordable senior housing developments in Los Angeles county now rely on waitlists to fill vacant units. When a resident moves out or passes away, property managers pull the next applicant from the list — usually on a first-come, first-served basis.

According to the Housing Authority of the City of Los Angeles (HACLA), the city-wide waiting list for public housing and Section 8 remains closed, and the Section 8 voucher list was last opened in 2022 — the first time in five years. As of September 2025, HACLA is still processing one-bedroom public-housing applications filed in June 2011.

Downstairs, her small vegetable garden has become one of her greatest joys — and the source of the fresh greens she cooks into her favorite Chinese dishes.

Ye uses the fresh greens picked from her garden in her favorite Chinese dishes. Jian Zhao for World Journal

Inside that kitchen, her caregiver, Ms. Lin, wipes down the counter and sweeps the floor. Lin visits four to six times a week to help with cleaning, grocery shopping, bathing, and short walks outdoors. Her work is funded through California’s In-Home Supportive Services (IHSS) program, which provides Ye 120 hours of paid caregiving each month.

Three times a week, Ye and her neighbours are picked up from their apartment complex at 8:30am and taken to a nearby adult day health center, bringing them back home by 12:30 p.m. The program offers an alternative to nursing homes for older adults who do not require 24-hour care. It helps participants stay mentally and physically active while reducing isolation.

At the center, Ye receives lunch and snacks, basic health monitoring, physical therapy, haircuts, light exercise, and a range of activities designed for Chinese seniors. Staff also accompany her to medical appointments when needed. It’s also where she learns the everyday information she needs to stay connected to her community and the wider world.

As Ye jokes, “They treat us like kids — so kind and patient.” There, she once joined dance sessions for years, karaoke, and made friends. Age has slowed her, but she still goes for the conversation and the warmth.

“I don't feel lonely,” she smiles.

Her son, who lives on the west side of Los Angeles, is in his seventies and cannot visit often. But he doesn’t have to worry too much about his mother living alone. Public agencies and non profits come to Ye’s apartment to help residents apply for eligible benefits — that’s how she received CalFresh food assistance, which provides about $200 a month for groceries, while Medi-Cal delivers her medications and covers clinic visits.

During the pandemic, local public-health nurses even came directly to her building to administer vaccines, and social workers helped renew their benefits. Despite not speaking English, Ye has had no trouble accessing the benefits she qualifies for.

Her apartment also qualifies for a utility subsidy from the local power company, greatly easing her electricity costs — support that is essential for many seniors who rely on oxygen machines or other medical equipment.

As an immigrant, Ye reported her pension income from China — roughly $1,000 a month — which still qualified her for about $600 in SSI benefits under Los Angeles County’s low-income threshold.

Together, these programs form a web of support that keeps Ye healthy, nourished, and connected — a living example of what health-policy researchers call the social determinants of health: housing, food security, and social connection.

Seniors Without the Same Luck

84-year-old Hua Qing hasn’t had the same luck as Ye. She pays $2,000 a month to share a room on the second floor of a house, plus utilities.

Hua works as an IHSS caregiver for her daughter, now in her fifties, who has long struggled with multiple mental and physical illnesses. Through the program, Hua earns about $2,000 a month for roughly 110 hours of care her daughter qualified for — just enough to cover rent and basic expenses.

“I’ve been waiting for subsidized housing for more than a decade,” she says. She checks regularly for updates on the waiting list and sometimes feels hopeless. Because of her daughter’s condition, moving has become routine. “I’ve moved 37 times in the past 30 years,” Hua says.

Other seniors without housing subsidies must squeeze into family boarding houses or tiny, window-covered rooms above grocery stores.

The demand for senior affordable housing far exceeds supply. According to the Harvard Joint Center for Housing Studies, in 2021 about 6 million renters aged 62 and older were eligible for federal rental assistance, yet available assistance was only sufficient to serve 36 percent of them. That left 3.7 million low-income older households eligible for help but unserved.

The national study also found that many face waiting lists that can last for years in major metropolitan areas and are often closed to new applicants.

At TELACU Las Palomas, the senior apartment complex where Ye lives, there are just 74 units, open only to residents aged 52 and older. The building manager says the last time the waiting list opened was in 2021 — and the wait can stretch up to ten years, depending on availability.

Senior housing in predominantly Chinese neighborhoods is even harder to secure. At Golden Age Village in Monterey Park, the waiting list hasn’t opened since 2014, according to the building manager. The complex has 120 units and remains full, with 148 residents whose average age is over 80. Many waited a decade or more to move in.

Funding Challenges and more

Local officials say that while the demand for subsidized housing continues to rise, funding and construction have not kept pace.

“We want to build more affordable housing,” says Monterey Park City Council member Thomas Wong.

“At the end of the day, building housing costs what it costs,” says Monterey Park City Council member Thomas Wong, who represents a city with the largest percentage of Chinese Americans in Los Angeles County and among the areas most affected by housing shortages. “The way to make it affordable is through subsidies — government funding, tax credits, or nonprofit developers layering multiple sources together.”

“We want to build more affordable housing,” he emphasizes. “We don’t want more people without housing.”

But the funding picture is bleak. “We’re losing a lot of federal funding,” Wong explains. “And the state, with its budget deficit, has had to cut back too.”

He points to Measure A —the Los Angeles countywide sales tax increase for homelessness and housing that passed last year— will bring in some new money, but it only fills part of the gap. “We can bolster some of that from the local level, but that won’t make up for what’s being lost from the federal and state levels.”

“And we expect to see a lot less federal and state money in the next few years to build affordable housing and provide health services for people in need,” he adds.

Beyond funding, Wong adds, there’s another obstacle: community resistance. “Funding is a big part of it, but another part is simply being able to site and build these kinds of units,” he says. “A lot of times residents aren’t excited about these projects and opposition grows, adding both time and cost.”

A Quiet Afternoon

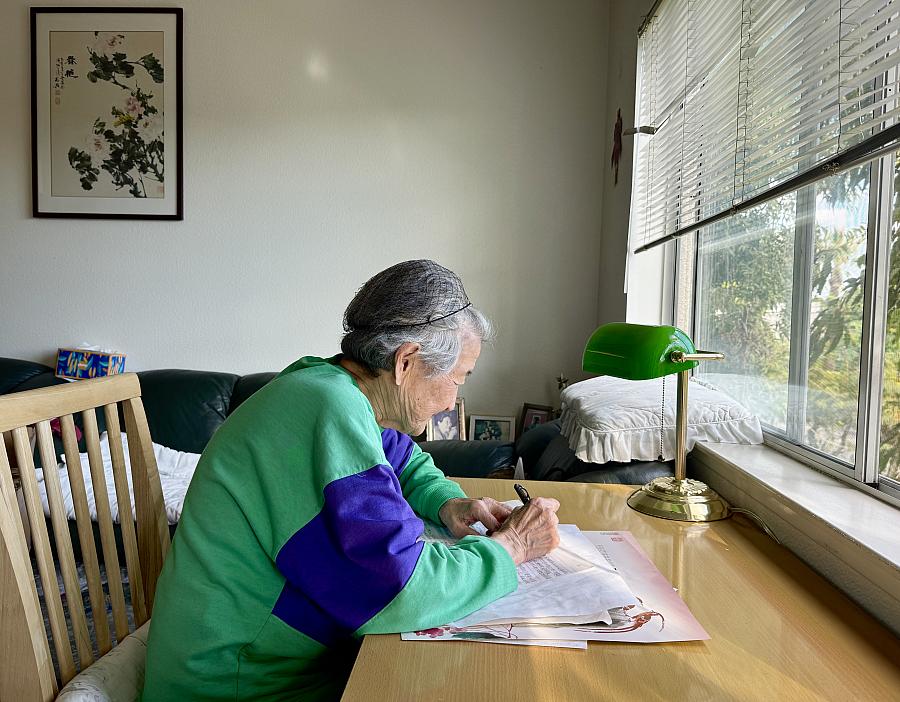

At home, Ye moves slowly through her apartment — a space of her own lined with family photos, Chinese books, and traditional paintings.

Ye spends her afternoons at the desk by a large window, copying poems and old song lyrics in neat handwriting. Jian Zhao for World Journal

She spends her afternoons at the desk by a large window, copying poems and old song lyrics in neat handwriting. Outside, palm trees sway under the Southern California sun.

“Here, I have everything I need,” she says with a smile. She no longer worries about food or rent — but she’s lucky.

This project was supported by the USC Annenberg Center for Health Journalism, and is part of “Healing California”, a yearlong reporting Ethnic Media Collaborative venture with print, online and broadcast outlets across California.