After ‘decades of broken promises’ will Central Valley air regulators finally end ag burning?

This is part of the series When the Smoke Clears, produced with the support of the USC Annenberg Center for Health Journalism Impact Fund.

Other stories in this project include:

Smoke from ag burning contributes to long-term health effects for Valley Latino residents

As air regulators phase out ag burning, what’s the alternative?

‘What am I going to do?’ Small growers especially apprehensive of a future without burning

A political fight and the legal ‘loophole’ that’s polluted the San Joaquin Valley for 20 years

With little confidence in California air quality regulators, advocates turn to Biden-Harris

The San Joaquin Valley Air Pollution Control District office in Fresno.

Monica Vaughn / Monicalvaughan@Gmail.Com

This is part of the series When the Smoke Clears, produced with the support of the USC Annenberg Center for Health Journalism Impact Fund.

Air quality regulators in the San Joaquin Valley for years delayed pollution cuts that would have improved public health. Instead they chose to allow the agricultural industry to openly burn waste in a region with some of the worst air quality in the country.

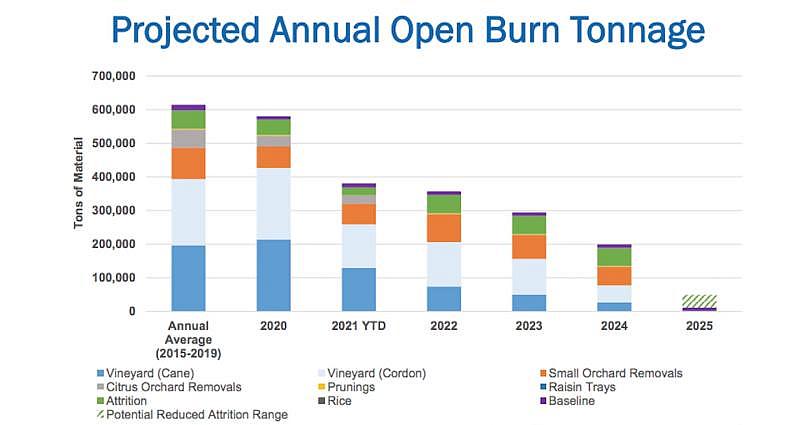

Now, state regulators with the California Air Resources Board (CARB) have set a deadline for the local San Joaquin Valley Air Pollution Control District to phase out open agricultural burning in the Valley by 2025, except in the cases of disease and pest concerns. This would help bring the region into compliance with federal air quality standards. Bolstering the commitment is $180 million in state funding to help farmers transition to alternatives.

The new plan clears a pathway for “an 80% to 90% reduction in the Valley in the next three years,” according to Michael Benjamin, chief of the Air Quality Planning and Science Division for the California Air Resources Board. Residents across the Valley will benefit, especially those in farm towns who he said currently see “plumes of smoke coming up from fields.”

Tania Pacheco-Werner, co-director of the Central Valley Health Policy Institute at Fresno State and a member of both the local and state air boards, said the clear goals in the new strategy to phase out ag burning are part of a larger plan to reduce emissions of harmful particulate matter known as PM 2.5. Particles of PM 2.5 are small enough to travel deep into the lungs and even the bloodstream, where they can cause permanent damage.

“All of those benefits to reduce PM 2.5 over time, especially those chronic, respiratory diseases a lot of us suffer from, I think we’re really going to see a change over the generations to come. That’s really exciting to me,” she said.

Smoke from wildfires has dwarfed many other sources of pollution in the Valley in recent years. Still, smoke from ag burning contributes significantly to the Valley’s PM 2.5 pollution problem. And, it’s a source regulators can control. It is generally responsible for 4% of annual PM 2.5 emissions in the Valley, according to Benjamin. Some years it’s more. Data shows it caused over 13% of PM 2.5 emissions valleywide in 2017.

Multiple studies link exposure to short-term particulate matter pollution to increased respiratory and cardiovascular events and premature mortality. A 2011 study funded by the district found ER admissions in the San Joaquin Valley are “strongly linked to increasing PM 2.5 across the region, with a higher risk in children.”

The air district is already implementing the plan and is on track to reduce burning by 70% from 2020 levels by the end of this year, according to spokesperson Jaime Holt. She said technological advancements developed with investment by Valley agriculture “are allowing us to implement a unique and aggressive phase-out strategy.”

“That’s a nice theory,” said Catherine Garoupa White, a clean air advocate and director of the non-profit Central Valley Air Quality Coalition. She and others said the Valley air district’s history of delayed action and bias toward the ag industry leaves them skeptical it will happen.

Mark Rose, Sierra Nevada program manager for the National Parks Conservation Association, said he is optimistic the phase-out will continue to occur, at least on paper. Still, he said, “we are cautious when it comes to anything that the air district promises to do because there’s decades of broken promises.”

The Valley air district prioritized the agricultural industry over public health for years

Nearly 20 years ago, California law directed the air district to phase out agricultural burning by 2010 to improve public health. That law included a caveat that the air district “may” postpone action if alternatives to ag burning are “economically unfeasible” to farmers and the burning will not cause a violation of a federal air quality standard.

Each time the issue of ag burning came before air regulators, the air district requested it be postponed and the state board agreed.

As a result, the air district issued some 250,000 permits to farmers to burn over 6 million tons of organic matter in the last ten years, data show, producing smoke in rural, mostly-Latino farm communities and adding thousands of tons of harmful particulate matter pollution into Valley air.

The air district did reduce permitted open agricultural burning by about 80% between 2003 and 2011. During that time, sending ag waste to biomass facilities to produce electricity was promoted by regulators and industry groups as the most cost-effective alternative to burning.

Half of those facilities shut down by 2015 as contracts expired and utilities chose not to renew. At the same time, the amount of ag waste increased during drought, as farmers ripped out water-thirsty orchards.

In response to farmer requests, the air district at that time agreed to allow burning for orchard removals greater than 15 acres, which had previously been banned. Farmers in that circumstance had to pay $750 an acre to burn the waste. By 2017, the amount of ag material burned grew to levels not seen since 2003. More than 900,000 tons were burned that year in the Valley.

Since then, burning has decreased as the air district increased restrictions and began offering incentives to alternatives to burning in 2018. By 2021, the air district recognized burning needed to be phased out, but again requested the ban on burning be delayed. This time, CARB agreed to delay action again, but set a hard deadline to phase the practice out by 2025.

All those decisions to postpone a complete prohibition on burning, according to Rose and Garoupa White, are a result of the air district’s bias that prioritizes agricultural industry profit over public health.

“They only look at the cost to industry. They do not look at the cost of health,” Rose said. “They don’t look at the missed school days, or the hospital bills that people in the Valley are paying, and the billions of dollars that it’s costing people in the Valley to be breathing in the air.”

In fact, a 2020 142-page report on agricultural burning by the Valley air district does not discuss potential health benefits from increased regulations, saying that estimating the population benefits of reduced exposure from reduced agricultural burning “is very difficult and not attempted in this evaluation.” There is no discussion of costs of increased emergency room visits, lost work days and treatments associated with exposure to smoke.

The same report includes pages and pages of detailed charts and tables about the profit margins of various crops and analyzes the expense to farmers of options for disposing of their waste.

Ag burning has been regulated for years. Burning is only allowed for certain crop types and only on certain burn days with favorable meteorological conditions. Regulators said the air district’s Smoke Management System places daily limits on burning so it will not cause or substantially contribute to violations of federal air quality standards throughout the region. But that doesn’t address impacts to those who live next to fields, including the health and financial costs they must bear.

While the air district argued the alternatives to burning were too expensive, it has simultaneously kept the costs of burning permits artificially low.

A 2015 state auditor’s report on Valley Air’s fee structure found that fees for burn permits at that time only covered about half the cost of running that program. Since then, the air district has raised those fees from $36 to $40 per permit. In the past, a single permit covered a burn of any size on one particular piece of property, but is now limited to 15 acres.

In an email, Holt, with the air district, said the agency has prioritized public health throughout the years “with strong focus on developing feasible alternatives to support expedited phase-outs, and continual evaluation of the issue through extensive public processes.”

“The Valley air district has worked hard with our state and federal partners, Valley agriculture, and residents for many years to implement the phase-out, including dealing with the very real difficulties in implementing a full phase-out,” she wrote.

Madeline Harris, who works with communities in Madera and Merced counties through the non-profit Leadership Counsel for Justice and Accountability, said the air district’s community outreach and response has focused more on agricultural interests than residents. For instance, residents have asked for a notification system to know when permitted burning will occur, but the air district has declined, saying it would be too difficult.

“That’s the low hanging fruit here,” said Rose. “At least let the people know that there’s going to be a burn happening so that they can go inside and close the windows. It’s fairly egregious there is just no warning system.”

In response to multiple inquiries about a notification system, Holt recently said the air district is now considering “the potential of more publicly available information regarding authorized burning.”

“Of course,” Holt said, “the underlying question will primarily be addressed through the aggressive and near-complete phase-out in open burning that is already achieving significant reductions and will be fully in place by the end of 2024.”

What it will take to end open ag burning in the Valley

Transitioning the Valley’s agricultural industry away from burning their debris to prioritize the health of communities will take massive behavioral change, both from farmers and regulators.

“What we’ve done is set a hard line in the sand,” said Pacheco-Werner. Since the deadline was set, she said, the air district has focused on farmer education and overcoming challenges that would prevent the industry from complying, including technological barriers and high costs.

“People are throwing challenges as to why we aren’t going to meet the deadline, and we’re going back to problem solve,” she said.

The air district has set aside $180 million to help farmers make the transition and worked with manufacturers to develop and produce more chipping equipment. Regulators have also agreed to change a rule. Incentive funding was originally limited to non-combustion alternatives to ag burning. In response to concerns that it is difficult to separate wire from woody debris in vineyards, regulators agreed to allow incentive funding to be used for “curtain air burners,” a technology that allows burning on site with reduced particulate matter pollution.

Garoupa White said that the air district “is always looking for the technological fix,” and not prioritizing what needs to be done for public health.

“They’re designing their rules around what industry wants,” she said. For the plan to work, “they would have to actually go out and do enforcement and ensure that behavior change was happening.”

Many farmers told KVPR the cost of alternatives even with incentives is too much to absorb, especially for smaller farmers; chipping equipment is in short supply; and some will likely turn to burning without a permit. Regulators haven’t announced any plans to increase enforcement efforts against unpermitted burning.

That’s concerning to clean air advocates, who say current enforcement efforts are weak.

“From the regulatory side, I have faith that they’re going to put in a ban and it’s going to help decrease the amount of agricultural burning that’s happening,” Rose said. “But then there’s also the enforcement side, and it’s making sure that people are following the rules. That’s where it’s a little worrisome.”

The current cost to farmers of getting caught burning without a permit has been cheaper than some of the alternatives to burning, at least before incentives for alternatives were available. While violation fines are not standardized and are determined on a case-by-case basis, public records show farmers who burned illegally paid between a few hundreds dollars to a few thousand.

A farmer in Ripon paid $1,500 for a violation issued June 14, 2019 for "orchard removal greater than 15 acres without prior air district authorization.” A Dinuba farmer paid $500 for "burning 14 acres of plum removal on or about October 2018 without authorization.”

The air district has not expressed any plans to enhance enforcement.

Another concern to air quality advocates: political pressure

State and local air regulators will likely face increased demand in the coming years to allow burning to continue. The amount of debris will likely increase as farmers are forced to remove crops to respond to market forces, or to fallow increasing numbers of acres as a result of water shortages and requirements under the Sustainable Groundwater Management Act.

“We know we’ve way over-planted in the San Joaquin Valley and what’s going to happen when we have to rip all of those crops out?” Garoupa White said. “The cheapest way of getting rid of them is lighting them on fire. So that underlying model of industrialized agribusiness, I think, further exacerbates the continuation of (agricultural burning).”

Farmers just “gotta deal with it,” said Dean Florez. He is a former state senator who introduced the 2003 law to ban agricultural burning and now sits as a member of CARB, the state regulatory agency that adopted the new plan and set the 2025 deadline.

“It’s an industry that is absolutely vital to California and the world,” Florez said. But it’s also an industry where we have to recognize, it lives next door to a lot of residents who have asthma and respiratory issues.”

That’s why the state agency will act as a guardrail to enforce the deadline, he said. “I’m still going to be on the Board the day of the phase out. It’s in stone. It will be phased out.”

Corporations own large amounts of agricultural acreage in the Valley, and owners are looking for a maximum return on their investments, Florez said. “And there’s nothing wrong with that. But part of that maximum return has to include the cost of disposal. Corporate folks just need to pull out their pencils and start to figure out how to pay for this.”

“It’s going to be tough,” Florez said. “A lot of industries have it tough. I’m not sure of an industry that gets to walk in and say ‘we just can’t, we think it’s too hard.’ The regs are hard, but they’re achievable.”

Monica Vaughan can be reached at monicalvaughan@gmail.com or on Twitter @MonicaLVaughan. Kerry Klein can be reached at kerry@kvpr.org or on Twitter @EineKleineKerry.

[This article was originally published by KVPR.]

Did you like this story? Your support means a lot! Your tax-deductible donation will advance our mission of supporting journalism as a catalyst for change.