‘What am I going to do?’ Small growers especially apprehensive of a future without burning

This is part of the series When the Smoke Clears, produced with the support of the USC Annenberg Center for Health Journalism Impact Fund.

Other stories in this project include:

After ‘decades of broken promises’ will Valley air regulators finally end ag burning?

Smoke from ag burning contributes to long-term health effects for Valley Latino residents

As air regulators phase out ag burning, what’s the alternative?

A political fight and the legal ‘loophole’ that’s polluted the San Joaquin Valley for 20 years

With little confidence in California air quality regulators, advocates turn to Biden-Harris

Dennis Hutson, who farms 60 acres in Allensworth, is one of many small farmers who worry they won’t be able to afford alternatives to ag burning.

Kerry Klein / KVPR

This is part of the series When the Smoke Clears, produced with the support of the USC Annenberg Center for Health Journalism Impact Fund.

When Dennis Hutson learned that a tool he relies on to maintain his row crops would be banned, he could hardly believe it. Soon, he will not be allowed to burn weeds and prunings to manage his 60 acres of okra, alfalfa and mustard greens in the unincorporated, historically Black community of Allensworth in Tulare County.

“Oh my, what am I going to do? That was my first thought because we have began to rely upon the burning,” he said.

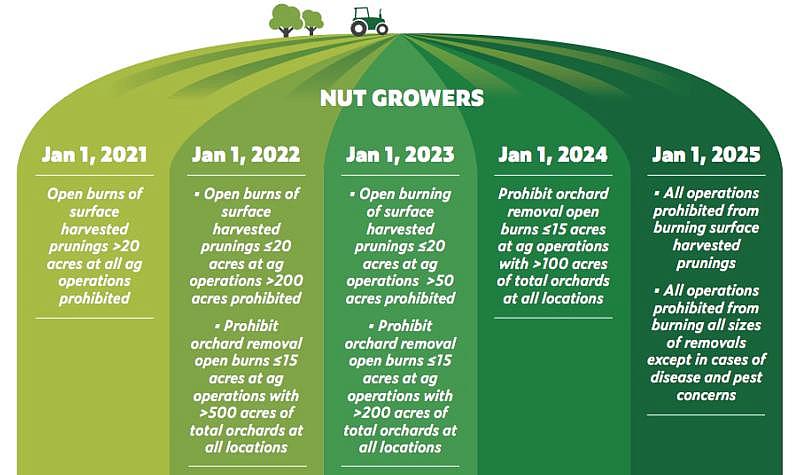

In 2021, nearly 20 years after a state law initially sought to ban ag burning, air regulators at the local and state level agreed on a plan to phase the practice out almost entirely by 2025. They promote whole orchard recycling as an alternative and make grants available to offset the costs. But farmers who run smaller operations remain skeptical they can afford it. The San Joaquin Valley Air Pollution Control District doesn’t distribute incentive funds based on need.

Hutson isn’t opposed to finding an alternative to burning. “I see the value in the elimination of the burn program because it's best for our air quality,” he said. “I'm not throwing my hands up. It's just that I don't have a solution just yet.”

Many growers, like Christopher Frith, have already begun adopting alternatives. Frith, who farms 1,000 acres of tree nuts and grapes near the Fresno County City of Caruthers, said he started phasing out the practice years ago by grinding up seasonal prunings. He incorporates them back into the soil.

But Frith is reluctant to adopt whole orchard recycling on large swaths of land because it’s expensive and time-consuming. He acknowledges the Valley’s dirty air, but he argues that burning produces only minimal smoke when done with thoroughly dried trees and on clear, windy days.

“We watch for everything. We watch for air conditions, we watch for winds, we watch for conditions in general to make sure that everybody around is going to be safe and clean,” he said.

State data show burning accounts for about 4% of the particulate matter released into the Valley annually. In some years it’s more. In 2017, open ag burning produced about 2 tons per day of PM 2.5 in the Valley, according to a resolution by the California Air Resources Board (CARB) that sets the 2025 deadline.

“These emissions are significant, not just in terms of potential implications for attaining air quality standards, but also for their impacts on local communities,” the document says.

The primary burning alternative comes with a hefty price tag

An analysis by UC Davis estimates that whole orchard recycling costs as much as $800 more per acre than burning. That’s why, with $220 million in incentives, the air district is now offering up to $600 per acre to recycle orchards and up to $1,300 per acre for vineyards. More funding is offered through the U.S. Department of Agriculture.

Frith, however, argued the price tag for recycling is vastly higher: “Thousands per acre compared to what it costs to burn,” he said.

Others are concerned about how growers will afford the practice once incentive funds have dried up. “Funding has definitely helped make this transition possible, but the funding set aside is only for the short-term,” said Fresno County Farm Bureau CEO Ryan Jacobsen in an email. “I am concerned about farmers facing these additional costs over the long-run with no mechanism of paying for the removals past a few years.”

Another obstacle to adopting whole orchard recycling is time. Frith says it can take months to secure one of the air district’s grants to offset the costs of the service, and even longer to book a contractor. He’s already begun planning for five years from now, when he intends to recycle 120 acres of aging almond trees and plant a newer variety.

In response to a KVPR survey, another farmer growing 120 acres of organic stone fruit in Fresno County said that he’d had difficulty securing a contractor to recycle his fields, claiming that they give preferential treatment to larger operations that’ll bring in higher profits.

Air regulators acknowledged in a 2021 report that chipping and grinding bottlenecks are a problem, which is only likely to worsen as prolonged drought and water restrictions phased in under the Sustainable Groundwater Management Act increasingly drive growers to fallow portions of their fields.

The air district recognizes contractor availability as a barrier, which is why the agency also directed public funds toward providing the Valley with new equipment for whole orchard recycling. Earlier this year, as part of the same pot of money available for incentives to growers, the air district allocated up to $30 million to expand chipping and grinding fleets, even working with a manufacturer of agricultural equipment to develop a new line of chippers and ramp up production.

Many growers are also dubious that whole orchard recycling saves on emissions at all. Heavy machinery kicks up dust and emits diesel exhaust which, depending on the size of the project, can persist for weeks or even months.

“The thousands of horsepower that it takes to chip is just astronomical,” said Frith. According to him, even his father-in-law, a grower who suffers from asthma and was told as a child that the Valley’s polluted air would be toxic to him, still prefers burning to the alternatives. “You're a lot cleaner to just burn it and be done with it and incorporate it back into your soil,” Frith said.

An analysis by UC Davis agrees that the diesel emissions from the vehicles involved in the practice can be harmful, a point also acknowledged by Todd DeYoung, Director of Strategies and Incentives at the air district. Still, he said, “I'll tell you it's a fraction of what an open agricultural burn might emit.”

Small farmers face big challenges

In Allensworth, Hutson is trying to become certified as an organic farmer, which means he’s come to rely on burning as an alternative to conventional pesticides. “It does work, at least as far as the farmer is concerned,” he said. “But in the meantime, what you have done is harmed the atmosphere. And so what am I going to do? I'm not really sure.”

The Valley air district in 2020 adopted a policy to allocate 30% of its grant funding for burning alternatives to growers with less than 500 acres. The agency has met that goal and distributed 35% to small operations.

Mark Rose is a clean air advocate at the National Parks Conservation Association who has lobbied to ban agricultural burning. He said the air district should direct a majority of funds to small farmers, citing them as the reason regulators gave for why burning should continue for so many years.

“They’re not equitable in how they divvy out those incentives. It’s usually first come first served…And it’s the small farmers that are being left behind,” Rose said. “That’s the hypocrisy of it. That bothers me the most, because we don’t want to put small farmers out of business. We didn’t push for this ag burn ban because we hate farmers. We pushed for it because we care about the population of the Valley.”

DeYoung, with the air district, said he and his colleagues recognize small operations have more of a challenge. “We worked very very closely with CARB and with the agricultural industry to develop our schedule for incentives to hit that sweet spot,” he said.

The air district also offers an additional $100 per acre in incentives to growers like Hutson who farm less than 100 acres. However, as of earlier this year, only 11 percent of disbursed grant funding had gone to growers on such small parcels, despite the fact that they make up nearly three-quarters of all of California’s farms.

“I find myself having to expend more resources to try to manage things in a healthy way, in a sustainable, regenerative way,” said Hutson.

The USDA, too, offers additional incentives to adopt whole orchard recycling to some growers, but it’s based on how socially disadvantaged they are rather than the size of their land.

Small growers say their options are so limited, and profit margins are so tight, that illegal burning may not be off the table. Data obtained via a public records request reveal that the penalties from air district for illegal burning vary depending on the scale and circumstances of the burn but can range from a few hundred to a few thousand dollars.

Christopher Frith has heard of some doing it already, even before the ban is fully in place. “They've said, ‘I've had an orchard piled up for six months and can't get a [permit]. I'm just going to light it,’” he said. “About 90 percent of them have lit it, walked away and nobody even knew anything.”

He, however, said he has committed to following the regulations. “We're going to have to,” he said, “either that or we're going to become outlaws.”

Kerry Klein can be reached at kerry@kvpr.org or on Twitter @EineKleineKerry. Monica Vaughan can be reached at monicalvaughan@gmail.com or on Twitter @MonicaLVaughan.

[This article was originally published by KVPR.]

Did you like this story? Your support means a lot! Your tax-deductible donation will advance our mission of supporting journalism as a catalyst for change.