Pregnant Behind Bars, Part 1: Second Chances

This series by WitnessLA’s assistant editor, Taylor Walker, was produced as project for the USC Annenberg Center for Health Journalism’s 2021 California Fellowship.

Her other work includes:

Pregnant Behind Bars, Part Two: When Housing Changes Everything

Pregnant Behind Bars, Part 3: When Things Go Wrong During Diversion

Pregnant Behind Bars, Part 4: The Mothers

Pregnant Behind Bars, Part Five: Looking To The Future

New Report Urges LASD To Release More Pregnant People From Jail, Improve Conditions

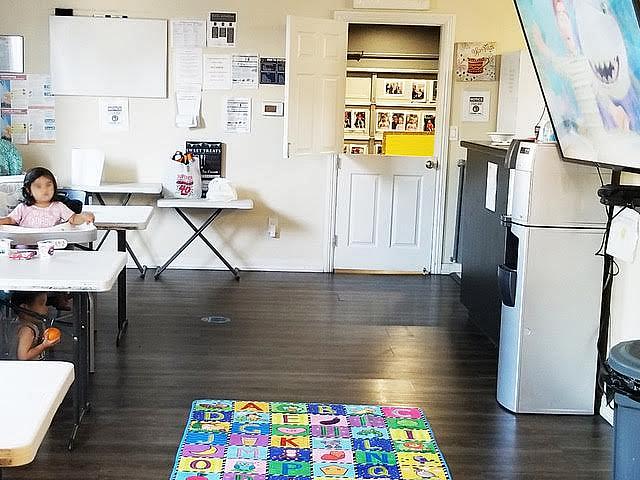

Featured image: Dining area inside the Maternal Health Diversion Program’s interim housing

In the first part of this four-part series, we look at how LA County’s Maternal Health Diversion Program disrupts the incarceration cycle by moving pregnant people out of jail cells and into supportive housing.

When Leslie Garcia was processed into the Century Regional Detention Facility, the main women’s lockup in Los Angeles County’s massive jail system, the mandatory health screening performed during intake revealed she was pregnant.

She faced the news with practical acceptance.

“I was gonna go for an abortion,” Garcia said. “I was facing a few years in prison. I had a background,” she said. “So they don’t give me chances.”

Garcia was arrested on December 31, 2019, New Year’s Eve, for a hit and run accident. She was not prepared to have a baby when she had no family to step in and help her, she said. While one family friend had taken care of her then-toddler son, Cole, a previous time Garcia was incarcerated, now there was no one who could take care of a new baby while she was in prison.

“Who am I gonna call to pick up [a newborn] from the hospital?” Any child born while she was in jail, she said, “was just gonna grow up in the system or be adopted.” She figured she would have no chance to be the child’s mother at all.

Her assessment was likely correct.

In 1997, U.S. lawmakers enacted a deadline after which absent parents — including parents away due to incarceration — can lose their parental rights forever if their child has been in foster care for at least 15 out of 22 months.

When Garcia talked about her pregnancy with a friend in jail, the friend told her about a new diversion program for pregnant and postpartum people offered by LA County’s Office of Diversion and Reentry (ODR).

Yet, Garcia was not optimistic the program could, or would, help her.

“I was like, Girl, I don’t get none of that,” she said.

Two days later, however, the diversion program’s then-director, Aubree Lovelace, knocked on Garcia’s cell door.

Through ODR’s Maternal Health Diversion Program, Garcia — and her children — did get that unexpected second chance.

During their first meeting, Lovelace told Garcia about the ODR’s Maternal Health Diversion program, the services it provided, and explained that Garcia’s charges did not preclude her from participating.

While every case is different, said Lovelace, the District Attorney’s office, and the diversion court judge, both had to sign off on her approval. A few serious charges, such as allegations of murder and attempted murder, are the only crimes that automatically make a person ineligible.

To leave jail, Lovelace said, Garcia would have to plead guilty to the hit and run charge, and serve some time on probation. Once she pleaded, however, she would receive housing and an array of services right away.

Presented with the possibility of a more hopeful future, Garcia agreed to the terms. She also realized she wanted to continue with her pregnancy.

Photo of Armani and Cole, courtesy of Leslie Garcia.

Now, Garcia lives independently with her little girl, a two-year-old named Armani, and her son, Cole, a newly minted first-grader, whom she would have had to leave behind for a second long stretch had a judge sent her to prison.

Because she was able to enter LA County’s then-new diversion program for pregnant people, she is, instead, raising two young, happy children.

Garcia is still not used to the help the program continues to provide for her and her kids, she said. “You’re just waiting for something bad, because that’s what we’re all used to.”

For pregnant individuals facing multiple years in prison, for those who cycle between homelessness and jail, and for those without a familial support system, ODR’s program offers unexpected hope and an alternative pathway — one that moves participants forward, out of jail cells, off of the streets, and into supportive housing for as long as they need.

Futhermore, Mothers who spoke with WitnessLA said they still received help from ODR long after they had technically completed the program.

Incarcerating mothers exacts a toll

Approximately 80 percent of the 2.9 million women jailed each year in the U.S. are mothers. Most are their children’s primary caregivers. And around 55,000 of those people are incarcerated while pregnant.

Women have become the fastest-growing incarcerated population in the U.S., even as overall national incarceration numbers have begun to slowly recede.

In 1980, there were just over 13,000 women in jails across the country, according to a November 2020 report from the Sentencing Project. By 1995, that number had nearly quadrupled, surpassing 51,000. By the end of 2018, the number of women in U.S. jails hit 114,500.

At the local level, between 2010 and 2016, the LA County Sheriff’s Department booked 173,000 women into jail at a cost of $752 million, according to a 2019 report by UCLA’s Million Dollar Hoods Project.

During that period, the top five single charges for women held in LA’s jail system were relatively low-level crimes: drug possession, DUI, driving on a suspended or revoked license, prostitution or solicitation, and theft or shoplifting.

In addition to having generally less serious charges than incarcerated men, incarcerated women are disproportionately survivors of violence and trauma.

Research also indicates that incarcerating mothers in turn heaps trauma on their children.

Kids with incarcerated parents are more likely to experience developmental delays, to drop out of school, and to later become incarcerated themselves.

A 2014 study by Kristin Turney, assistant professor of sociology at UC Irvine, found that having a parent behind bars can be more damaging to a child’s well-being than divorce or even death of a parent. Those we spoke with in the Maternal Health Diversion program told stories of the struggles their older children faced while they — the mothers — were incarcerated.

Unfortunately, too often critical needs of these vulnerable community members are overlooked.

Funneled into foster care

Many of the women WLA interviewed for this series were single mothers. Several of the moms, including Garcia, had family members or close family friends who were able to take care of their other children while they were in jail.

Others told us their kids were funneled into the foster care system instead.

Michelle Loest falls in the latter category. She is sober now, but her past struggle with drugs meant that her first born, a boy named Adrian, had already spent some time in foster care by the time she found herself in CRDF, as LA’s women’s jail, located in Lynwood, California, is commonly called. Loest was pregnant with her second child, Emma, now a year old.

As Loest’s days in jail ticked by, she became increasingly worried that the child welfare system would never return her son to her when she was released. The foster parents caring for the then-six-year-old Adrian were looking to adopt a child.

“Last year, in January, I was in jail, and my son had already been in foster care for a year. I really thought that they were going to adopt him,” she said.

Adrian’s foster parents were very kind to her son, Loest said. But the boy’s behavior changed with the arrival of COVID, which caused him to lose nearly all contact with his mother due to the additional complication that she was in jail during a pandemic. Doctors put Adrian on medication to address the behavior issues, a decision Loest still questions.

“I really think that the social worker just saw how much my son really wanted to be with me, and loved me,” she said.

Struggles persist long after incarceration

When mothers return from lockup, they are more likely than their male counterparts to experience homelessness, unemployment, and other barriers to successful reentry — all of which negatively impact their children.

With this and other issues in mind, over the past five years, LA County officials have worked to improve care for women in the jail system, especially for pregnant and postpartum women. One program allows mothers to breastfeed and pump milk. Another offers space for moms and their young children to have physical contact and play.

Unsurprisingly, research shows that keeping babies with their mothers in prison nursery programs produces better outcomes for kids than separation. Yet, far better — and far cheaper — than incarcerating pregnant and postpartum women are initiatives that keep them in their communities.

ODR tries something new

When ODR was created in 2015, it was focused primarily on improving reentry services for those who were incarcerated, as well as diverting individuals with serious mental health needs out of LA County’s over-stuffed jails.

In 2018, ODR launched a similar program, this time for pregnant people, offering supportive housing where mothers can live with their children.

According to Dr. Kristen Ochoa, Medical Director of the Office of Diversion and Reentry, the Board of Supervisors approached ODR with the request.

“And I was like, “Sure, we can try, and see how it goes over.’”

Ochoa said she and the ODR team first had to gauge the appetite of Los Angeles County judges and prosecutors for such an endeavor. “We just did a few cases to start, and it really was successful.”

A year before, testing during jail intake found that 864 people (5.2 percent of those jailed) were pregnant. While most jail stays are short (52% of the women’s jail bookings resulted in stays fewer than six days), that year, thirty-five of the pregnant individuals gave birth while in LA County Sheriff’s Department custody.

Of the resulting 35 kids, 16 were transferred directly into their maternal grandmother’s care, and 13 were given to other family members. Six were taken into the child welfare system.

Since the Maternal Health Diversion Program’s 2018 inception, 189 pregnant people have been able to return to their children and their communities, rather than remain behind bars, according to the latest count in a recent ODR progress report.

A total of 110 of those people were still officially receiving ODR services, as of July 2021.

Diversion participation numbers as of July 2021.

The maternal health program is modeled on ODR’s successful Mental Health Diversion Program, but obviously the newer program has somewhat different goals.

The focus, said ODR Director Judge Peter Espinoza, is on ensuring that the women receive prenatal care and specialized services that help them remain drug free, and help them deliver healthy babies.

“This population, unlike other populations that we deal with, aren’t exclusively people suffering from a serious mental illness,” Judge Espinoza told WitnessLA. Instead, they are usually in lockup because of “some other sort of unmet behavioral health needs,” like substance use disorder, “or they are engaged in some sort of criminal behavior as a way to escape intimate partner violence,” Espinoza said.

ODR works to meet those unique needs through a harm reduction approach that starts with getting people into housing.

It helps that mothers in the program are permitted to mess up. Sometimes, they are re-incarcerated. Yet, the diversion court and ODR will often allow mothers to return to the diversion program to try again.

“This approach asserts that many persons are in jail because of a systematic failure to adequately care for them,” Dr. Ochoa wrote in a 2019 report about ODR’s Mental Health Diversion.

“It is an approach that re-creates systems to provide permanent care,” without limits, “for the lifetime of the patient.”

To accomplish this, she wrote, “the new system must say, ‘Yes’ with the same veracity and availability of a jail bed, and with the same ease and routine of a jail booking.

“It has to be flexible and forgiving; it has to be a commitment to ‘care first, jail last.’”

This series by WitnessLA’s assistant editor, Taylor Walker, was produced as project for the USC Annenberg Center for Health Journalism’s 2021 California Fellowship.

[This article was originally published by WitnessLA.]