Alameda County zip codes with highest COVID-19 case rates struggle to have matching testing

This story is part of a larger joint project led by Annika Hom and Lydia Chavez, participants in the 2020 Data Fellowship whose reporting has focused on whether resources are ending up in the hands of those most affected in San Francisco.

Other stories in this project include:

Covid-19: San Francisco’s Latinxs are infected at higher rates than Latinxs in harder-hit cities

Early 24th St. rapid test results show 9 percent positivity, 10 percent for Latinx

UCSF/Latino Task Force BART Covid-19 testing site appears to be the most effective in San Francisco

Jane Garcia, the CEO of La Clinica de la Raza, spoke at a presser detailing the effects of Covid-19 in the Fruitvale on Oct. 16.

Photo by Annika Hom.

For months, epidemiologists and medical experts have argued that key to controlling the pandemic is to bring testing to the places where Covid-19 is spreading the fastest.

Nevertheless, by early December, testing was not even close to keeping up with the virus in three Oakland neighborhoods that consistently top Alameda County’s list for fastest viral transmission.

The Alameda County data resembled an almost inverse relationship between cases and testing: More-affluent zip codes reported plenty of testing, but high-risk neighborhoods overrun with Covid-19 all reported low rates.

“Despite [local testing] efforts, the discrepancy persists. It’s unclear to me why this is still the case,” said Dr. Kim Rhoads, a UCSF doctor and the director of UCSF’s cancer center, who helped launch a mass Black testing campaign in Oakland this fall. She added in an email to Mission Local that while the county is trying to boost testing in affected zip codes, “I don’t think the Alameda County strategy is particularly strategic.”

The same is true in San Francisco. But the difference in Alameda County is that its health department appears to have meted out its testing resources relatively equally, if not more to underserved areas where the virus is most prevalent.

“I think we recognize that we need to get more testing to the area that you’re talking about,” said UCSF doctor Kirsten Bibbins-Domingo. “A good question is, why hasn’t that happened?”

Where Covid-19 is spreading and where people are testing

The disparity in Alameda County appears to be created by a number of factors: private insurers being more prevalent in wealthier zip codes, fewer county-controlled tests than other counties like San Francisco, a suboptimal strategy by the Alameda County Health Department, and individual willingness to get tested.

Mission Local found the disparity by analyzing 42 Alameda County zip codes’ Covid-19 data through Dec. 1. Berkeley zip codes were excluded, because the city runs its own health department and had the highest testing rates in the county.

Elmhurst, Fruitvale and Stonehurst/Sobrante Park, however, the three central and East Oakland areas where Covid-19 has spread the quickest, were all testing at rates lower than at least a dozen other zip codes less likely to have Covid-19 cases.

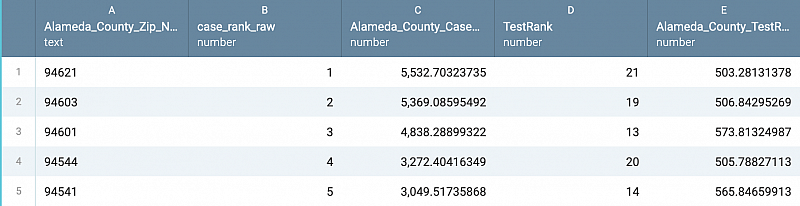

Just before the winter surge descended, Mission Local’s analysis found that the zip code encompassing Elmhurst placed 21st in testing rates out of 42 zip codes in Alameda county, Fruitvale’s zip code placed 19th, and Stonehurst/Sobrante Park’s 13th. They placed first, second and third, respectively, for highest case rates as of Dec. 1.

These are all historically working class or poor neighborhoods with high Latinx populations, Oakland Public Librarian Steven Lavoie said. Studies have shown that low-income Latinx residents are more at risk for Covid-19 because they are more likely to be essential or frontline workers who must leave the house to work. Many return to overcrowded housing where the virus can more easily spread.

Alameda County zip codes ranked by highest case rate. Data source: Alameda County Department of Public Health, Dec. 1, 2020. Analysis by Annika Hom.

These zip codes were also ranked extremely vulnerable according to the 2016 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Social Vulnerability Index, which is the center’s formula that uses factors like income, living situation, and ethnicity to determine “social vulnerability.” The center defines that as the “the potential negative effects on communities caused by external stresses on human health.”

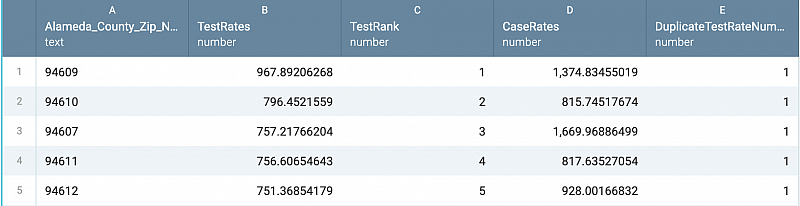

Meanwhile, zip codes encompassing North Oakland’s Temescal neighborhood, West Oakland and the city of Piedmont all ranked as the top three testing areas, despite ranking 20th, 33rd and 14th in covid case rates.

Alameda County zip code ranked by highest test rate. Data source: Alameda County Department of Public Health, Dec. 1, 2020. Analysis by Annika Hom.

These are areas known for wealth and luxury housing — and are where residents were testing the most. In a 2015 USA Today article, Piedmont ranked among the top 10 richest towns in the United States. Though West Oakland is historically Black, it has gone under increasing gentrification, causing less Black resident turnout during Rhoads’ prior testing campaign.

Alameda County is reporting more than 22.5 new cases per 100,000 people a day. In order to cross into the state’s most restrictive reopening tier, counties had to report more than seven new cases per 100,000 people a day. With thousands now dying daily across the nation, medical experts said figuring out how to close that testing and engagement gap will be critical.

A situation “more complicated than any of us can comprehend”

Alameda County’s nearly inverse relationship between covid case and testing rates surprised Jane Garcia, the CEO of La Clínica de La Raza, a health center in Fruitvale.

“I think I’m just learning that from you, because I know that we’re testing more and Native American Health Center is testing more,” Garcia said.

Testing demand at La Clinica increased post-Thanksgiving. Garcia said the clinic was testing double its normal amount at 200 per day, largely thanks to county support. The covid positivity on its tests after Thanksgiving was between 25 to 30 percent. At the time, the citywide positivity rate was hovering around 4.5 percent.

Staffers at other clinics concur with Garcia, saying that the Alameda Public Health Department has put in mobile and pop-up testing sites in underserved neighborhoods like the Fruitvale when these covid health disparities became apparent.

It also financially supported local clinics that test these communities and increased overall testing by 25 to 50 percent by December, the department said in a statement, and doubled test capacity at most sites.

During the beginning of the pre-Thanksgiving surge, roughly 3,122 tests were controlled by Alameda County. The department did not tell Mission Local the exact number of tests administered at each of its sites, but it did state at least 1,400 were used at the underserved and highly impacted neighborhoods each day — which amounts to almost 49 percent of its controlled tests at the time.

Alameda County has about 1.67 million residents and department-controlled testing accounts for only 40 percent of all reported tests. There doesn’t appear to be, and the department did not identify any fixed sites as substantial in output as San Francisco’s Color sites, though Alameda County’s controlled testing peak in December averaged nearly 5,000 tests. In contrast, San Francisco has roughly 5,000 tests a day at its disposal and a population of 881,000.

But, unlike the situation in San Francisco, in which neighborhood groups and clinics complain about getting too few tests, clinics in Alameda County view the health department as an ally.

The Health Department has been “fantastic” and “has done all they can do,” said Aaron Ortiz, the CEO of the Latinx nonprofit La Familia Counseling Service that runs testing sites in Hayward and Alameda County’s unincorporated areas of Cherryland. This area has over a 40 percent Latinx population and the county’s next highest covid case rates.

But just putting up a testing site doesn’t mean people will come. “I think that the additional challenge is making it available, and then ensuring that we reduce the barriers and increase the opportunity for the people who need it most,” Bibbins-Domingo said.

Gary Fanger, the chief operating officer of HR Support Pros, which conducts Alameda testing, agreed. Fanger said at first he thought the affluent — those that some officials deem the “worried wealthy” — would test more than underserved areas because of barriers like drive-through testing.

While Fanger said in his experience that’s no longer the case, it is hard to say definitively. In fact, white testers have outpaced Latinx testers in Fruitvale and East Oakland despite higher Latinx populations and more Latinx covid cases, according to November Alameda County data obtained by Mission Local from the Alameda County Health Department.

Also, higher testing in Piedmont and North Oakland could be potentially explained because of their proximity to Berkeley, which churns out lots of tests. During the period from Nov. 1 through Dec 15, 1,907 tests went to Oakland residents, according to the Berkeley Health Department.

Fanger said testing rates also fluctuate depending on an individual’s desire to be tested. Generally, that’s a different story between the well-to-do and underserved minority groups or during covid lulls or surges.

As several studies found, Black and immigrant communities can be distrustful of government and health institutions, in part due mistreatment in the past. A way to mitigate that is by boosting community engagement and rebuilding trust.

Rhoads learned in the Black Oakland testing effort that even historically Black health clinics were catching few Black residents for covid testing; holding a campaign distant from healthcare aesthetic and that centered more on community provided better results in her campaign.

“Mobilization of community by community members to test at a location lacking institutional labels can successfully engage the so-called hard to reach communities at high rates,” Rhoads said. “It is unclear if just popping up testing sites in strategic locations without community participation in the delivery process will have similar effects.”

The Health Department acknowledged that “differences in testing rates are also likely linked to existing inequities that haven’t been and won’t be fully addressed in the limited span of this pandemic.”

More testing could possibly occur with more funding, Fanger said. When Mission Local asked whether lack of funding would affect testing expansion, the Alameda Public Health Department emphasized in a statement that resources were being allocated to underserved areas. More mobile testing is planned, too, as “we transition to a testing model that leverages state and local resources and partnerships, rather than CARES dollars.”

With so many social and health elements to consider, solving these inequities won’t occur overnight, Fanger said. “It’s more complicated than any of us can comprehend.”

And, since early December, Alameda County has improved in testing; unfortunately, case rates in Elmhurst and Fruitvale still soar. But, while the pandemic rages, case and test disparities continue, and especially impact the Latinx population, which accounts for 41 percent of total cases in Alameda County, but only 22 percent of the population. Rhoads and other Oakland clinics and activists have conversed with Black residents to try to dispel fears of vaccines as Black communities confront a disproportionate death rate.

Bibbins-Domingo said that the patchwork of testing and the hurdles public health and healthcare have had to face in the pandemic is frustrating. However, the “absolute goal” should be to increase testing to those who need it most.

“It requires coordination,” Bibbins-Domingo said, “but it’s not an excuse.”

This story was supported in part by the USC Annenberg and the 2020 Center for Health Journalism Data Fellowship.

[This story was originally published by Mission Local.]

Did you like this story? Your support means a lot! Your tax-deductible donation will advance our mission of supporting journalism as a catalyst for change.