COVID-19: San Francisco’s Latinxs are infected at higher rates than Latinxs in harder-hit cities

This story is part of a larger joint project led by Annika Hom and Lydia Chavez, participants in the 2020 Data Fellowship whose reporting has focused on whether resources are ending up in the hands of those most affected in San Francisco.

Other stories in this project include:

Alameda County zip codes with highest COVID-19 case rates struggle to have matching testing

Early 24th St. rapid test results show 9 percent positivity, 10 percent for Latinx

UCSF/Latino Task Force BART Covid-19 testing site appears to be the most effective in San Francisco

Bay Area Phlebotomy Laboratory Services, a company that grew from a just a handful to 80 employees during the pandemic, collected samples during the 24th Street UCSF/Latino Task Force pop-up around Thanksgiving.

Photo by Mike Kai Chen

San Francisco loves to compare itself to other cities, especially when it is doing spectacularly better. We expect city officials to do this and they rarely disappoint.

Two favorite Covid-19 statistics that elicit frequent backslapping among SF officials include San Francisco’s testing rates — we do more than anywhere else in the country — and the city’s lower covid mortality rate. The latter is a marvel. The former, not so much, as testing is only now moving to the high-risk communities.

The San Francisco Chronicle jumped on the cheerleading bandwagon earlier this week, looking at how the city’s recent case rate compares to other large metro areas.

“California is now the epicenter of the nation’s latest coronavirus surge,” the piece began, but quickly moved from the bleak to the upbeat. Lo and behold, San Francisco has a lower new case rate than other major cities; only Seattle fared better. “Others are two, sometimes even three times higher, including big cities in Texas and several Southern California counties.”

Another reason to cheer? Probably not. Generalized case rates, as epidemiologists have pointed out throughout the crisis, minimize the importance of who is getting sick. In this pandemic, the most impacted, depending on the city, are either low-income Black residents or low-income Latinx residents.

Looking at overall case rates, said Peter Khoury, a data scientist who lives in the Mission District, “builds a sense of complacency, and you don’t see your weak spots — and the virus exploits the weak spots. In San Francisco, that [weak spot] is the Latino population.”

But, the Chronicle piece made us wonder – maybe San Francisco is doing much better in the Latinx community compared to the other major cities.

Alas, no. San Francisco may be richer and hillier, but some of its Texas counterparts with a lot more poverty and Trump voters have lower case rates in their most-impacted Latinx communities.

The Chronicle’s look at case rates in 20 counties that include Houston, Dallas, Seattle, Indianapolis and Denver showed San Francisco’s with the second-lowest recent case rate after Kings County, which includes Seattle.

But, looking at the most impacted communities in those cities tells a wholly different story.

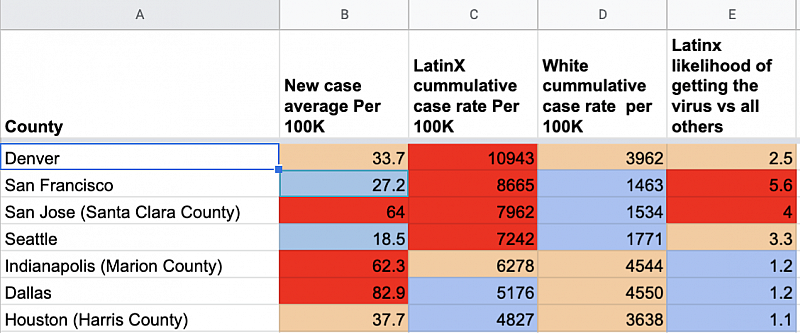

San Francisco has among the highest case rates in its Latinx population. At an adjusted rate of 8,664 per 100,000 residents, San Francisco ran well ahead of Houston at 4,827, Indianapolis at 6,278 and Seattle at 7,962. Only Denver’s rate was worse — 10,943 per 100,000 residents.

San Francisco did top out in two categories: it is the worst place for a Latinx resident to live, in terms of their chances of getting Covid-19. Much worse. A Latinx resident in San Francisco is five times more likely to get covid than other San Francisco residents.

And, it’s a swell place to be white: San Francisco has the lowest overall case rate for whites — 1,463 per 100,000 compared to those living in Marion County, which includes Indianapolis, Indiana, with 4,544 cases per 100,000 in the white population. Whites are also more than two times less likely to get infected with covid in San Francisco, according to Mission Local’s analysis.

This appears to speak more to disparities than to the size of the Latinx population. The Latinx community makes up 15 percent of San Francisco’s population. On the contrary, Latinx residents make up the biggest population in Dallas County, but the probability that a Latinx resident will get sick in Dallas is only slightly higher than that of a white resident.

Khoury said the ratios point to greater income disparities. San Francisco’s Latinx residents are predominantly low-income and more likely to live in crowded housing.

Here and elsewhere, poverty can lead to overcrowded housing, low-paying frontline jobs and an inability to access medical affordable medical care. For example, in two Indianapolis areas where covid has spread the fastest, between 15 and 20 percent of residents live below the poverty line, and most residents are white.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention acknowledged these effects, and created a formula that uses factors like income, living situation, and ethnicity to determine “social vulnerability. ”

The center defines that as the “the potential negative effects on communities caused by external stresses on human health.” It’s unsurprising to find that many of the areas where covid is rampant across the country also score as “highly vulnerable” on this metric — for example, neighborhoods in Tarrant County, Texas and Indianapolis — meaning that lack of resources and extra stresses could potentially exacerbate effects of the pandemic.

Though the city is moving to address inequities now with more testing and better outreach, it’s also been no secret that the hardest-hit neighborhoods have long been underserved and “highly vulnerable.”

“We have communities where there has been systemic underinvestment hit hardest by the pandemic,” Dr. Kirsten Bibbins-Domingo, the vice dean of population health and health equity at UC San Francisco said earlier this month. “We need to make sure that people have the resources to be able to take the steps to protect themselves and their family. And collectively, we as a city have to be able to do that to protect the city.”

In other words, the metric that will matter at the end of all of this is how San Francisco measured up in treating its most vulnerable and impacted populations.

Arnold Perkins, the former director of the Alameda County Public Health Department, told Mission Local back in fall that “If [Covid-19] was a war, you have poor people on the front line, and you have rich people in back.”

It’s no secret that’s what’s happening in San Francisco, too. The Bayview, the Mission, and the Tenderloin have been leading the way for covid spread and positivity.

Singing San Francisco’s praises requires one to overlook that.

This article was supported in part by University of Southern California Annenberg and the USC Center of Health Data Fellowship.

[This article was originally published by Mission Local.]

Did you like this story? Your support means a lot! Your tax-deductible donation will advance our mission of supporting journalism as a catalyst for change.