In Arkansas, youth offenders get very different treatment depending on the judge

Chad Day reported these stories for the Arkansas Democrat-Gazette with the support of the Fund for Journalism on Child Well-Being and the National Health Journalism Fellowship, programs of the Center for Health Journalism at the University of Southern California's Annenberg School of Journalism.

Other stories in the series include:

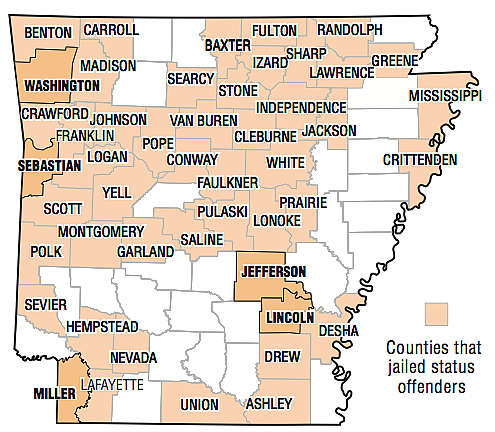

Photo by Arkansas Democrat-Gazette. A map and information about status offenders.

In roughly two-thirds of Arkansas counties last year, children went to youth lockups for skipping school, disobeying their parents or running away from home.

In the other 27 counties, children who did the same things remained free.

The youths are known as status offenders because they’ve violated laws that apply only to children. Federal and state laws give the courts the power to detain them if they violate court orders.

But in Arkansas, whether the youths go to jail depends largely on the philosophies of their judges and the ability of their counties to pay for them to be locked up.

This disparity is a little known truth about the juvenile justice system in Arkansas, where court proceedings are confidential, data on status offenders are limited, and the focus of state officials and lawmakers has centered on juveniles who commit serious crimes and cost thousands of dollars to detain.

Child welfare law professor Jerald Sharum says status offenders are being treated differently because of things that are out of their control — a situation that undermines the fairness and equality that are supposed to be guaranteed by the courts.

“It is a problem because you’re not really getting the same shake,” said Sharum, an adjunct professor at the University of Arkansas School of Law in Fayetteville.

Marcus Devine, director of the Arkansas Division of Youth Services and chairman of the Youth Justice Reform Board, said the pattern of inequality is “troubling.”

“We need to look at why that is and how that could be because the truancy in Chicot County shouldn’t be treated differently from the same truancy in Benton County,” Devine said.

Arkansas Supreme Court Justice Rhonda Wood, who was a juvenile court judge from 2007-12, said money and proximity to youth lockups account for some of the disparity.

“Geographically, I would really look at where they’re at with the detention center because that makes all the difference in the world,” Wood said.

Arkansas has 14 juvenile detention centers spaced out around the state. Each is county-operated. For judges in counties with juvenile detention centers, much of the cost is contained in the county’s budget.

But judges who don’t have such centers have to weigh whether it’s worth the $85 per day that some lockups charge to house out-of-county kids.

Eighth South Judicial Circuit Judge Brent Haltom, one of three juvenile court judges presiding in Miller and Lafayette counties, said cost explains figures from the Youth Services Division that show a big difference between his two counties.

In 2014, status offenders from Miller County were booked into the juvenile detention center at least 33 times for contempt of court. But in Lafayette County, no status offenders were sent to the Miller County lockup for contempt last year, according to the state agency’s data.

Haltom said he’s locked up only one Lafayette County status offender this year, the first one he can remember from that county since he took the bench in 2011.

“If Lafayette County sends one to Miller County, it costs them so much per day to house them, and it’s pretty steep,” Haltom said, “whereas in Miller County it’s part of our budget.”

But tight budgets and proximity to lockups don’t explain all of the disparities in how status offenders are treated.

Last year, Circuit Judge Earnest Brown, who presides in Jefferson and Lincoln counties, ordered status offenders to juvenile lockups 193 times for violating his orders.

Less than an hour away in Little Rock, Pulaski Circuit Judge Wiley Branton didn’t order any status offenders jailed last year.

Statewide, status offenders from 48 counties were detained in juvenile detention centers last year, according to booking sheets obtained under the Arkansas Freedom of Information Act.

In 27 other counties, no status offenders went to lockups, the records show.

Pulaski County accounted for one status offender spending time in lockup, a decision that was not made by Branton.

For Branton, locking up youths is a matter of judicial philosophy.

Pulaski County’s juvenile detention center is just a few miles from Branton’s court. But he doesn’t see it as an option for children who haven’t committed delinquent acts.

Branton sees his role in status-offender cases as a facilitator of services — assessing the needs of the children and connecting them with counseling, mentoring, substance abuse treatment or other things that will help them succeed in school or control their behaviors.

Branton acknowledges that his system isn’t perfect.

“I do think that I’m a little bit less effective in getting some kids to go to school because I no longer have the threat or have the response of a contempt proceeding,” Branton said.

“On the other hand, I think I’m doing less harm.”

Brown said he believes his lockup approach has helped many youths. He uses detention only after he’s exhausted all other options, he said.

But Brown said he wasn’t aware of the scale of the geographic disparity in how status offenders are treated in the state until he was approached by the Arkansas Democrat-Gazette about his detention numbers this fall.

In late November, he said he was considering cutting down on the number of status offenders he locks up.

“We really do need to try to be uniform across the state,” Brown said.

[This story was originally published by the Arkansas Democrat-Gazette.]

Photo by Arkansas Democrat-Gazette.