Asylum Seekers from Myanmar in NorCal Live Uninsured in Poverty Despite Medi-Cal Expansion

The story was co-published with AsAmNews as part of the 2024 Ethnic Media Collaborative, Healing California.

Hazel Su, an asylum seeker from Myanmar, lived without medical insurance until she found out that she was eligible to apply for Medi-Cal.

Photo by Jia H. Jung

Inside a little house in Daly City, California, Hazel Su and her friend fit twin-sized mattresses onto the floors of rooms already occupied by strangers.

The women from Myanmar, in their early 20s, found a broker through the Burmese Facebook community who located eight residents in a three-bedroom house. The tenants gladly made space for additional tenants to reduce rent to $625 per month per person.

Su is one of several hundreds who have migrated from Myanmar to the Bay Area of California with student visas after the Burmese military’s 2021 coup and are seeking political asylum to resettle in the U.S.

Asylum-seekers from Myanmar in Northern California, like Su, are so focused on paying rent and other living expenses in addition to helping family back home that they often don’t prioritize their own health. When they need medical care, their part-time and informal jobs don’t provide insurance, the state’s health insurance options are too confusing to navigate with too few community workers who can help.

Insurmountable cost of care

When civil warfare intensified in Myanmar after the coup, Hazel Su decided to leave the country. She came to the United States in December 2022 with money for one semester of student tuition and rent.

She enrolled at Skyline College in San Bruno, California, one of three institutions in the San Mateo Community College District.

The cost of attendance included health insurance but Su never put her student plan to use, not even for a physical or dental exam.

“I had no problems, then,” she said, referring to her health.

Besides, Su spent all of her time studying or working. Like so many others sharing her journey, she picked up under-the-table shifts at a Burmese-managed sushi shop at a mini-mall and night shifts at a trendy Korean restaurant in downtown San Francisco.

In May, Su developed abdominal pain so intense that she could not go to work. She sought emergency care and learned that she had an ovarian cyst.

The hospital gave her a number to call for a follow-up medical attention. But that practitioner was not taking new patients. Su reached out to other gynecologists near her but none of them was accepting new or uninsured patients, either.

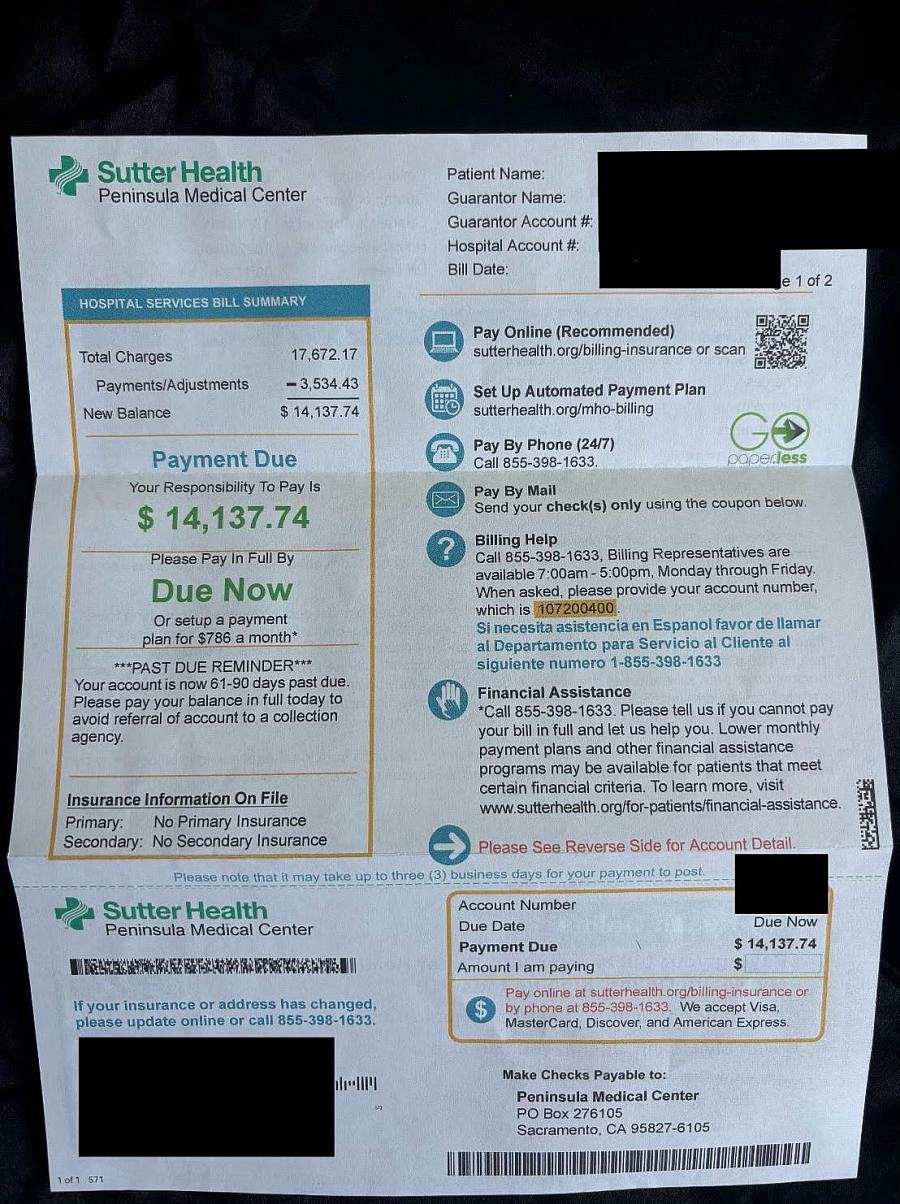

Meanwhile, Su began to receive bills, the largest of which amounted to $14,137.74 — double the college tuition for a semester.

Medical bill

Courtesy of Hazel Su

The traditional medicines her mother had packed for her when she left Myanmar were all used up now, so Su switched to Ibuprofen and chamomile tea to bear the pain.

Only then did she learn from housemates and other Burmese community members about Medi-Cal, California’s free health insurance coverage for qualifying low-income residents.

Uncovered California

On Jan. 1, 2024, California expanded eligibility for Medi-Cal, the state’s implementation of Medicare, so that all undocumented adults meeting income eligibility requirements can be eligible for free insurance. For an individual, the income must not exceed $1,731.92 a month to qualify for the program.

If Su is approved for Medi-Cal, the insurance will retroactively resolve her medical expenses dating back to three months from when she submitted her application.

Not every asylum seeker from Myanmar is accessing these benefits.

Min Thein is a Burmese community outreach worker and interpreter at the Center for Empowering Refugees and Immigrants (CERI) in Oakland who works with Alameda County.

He broke down why asylum seekers have less systemic access to American health care systems and other social services than refugees do.

Refugees enter the U.S. with protection by a United Nations agency. They receive mandatory physical and mental health screenings, vaccinations, and treatments upon arrival. And United States Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS) provides them with social security numbers and work authorization permits within 90 days.

Political asylum, on the other hand, is for people not classified as refugees but want to resettle outside of Myanmar because of the dangers and threats there. They must wait nearly 6 months after arriving in the U.S. to file an application for asylum, paying thousands of dollars in fees for an attorney and interpreter.

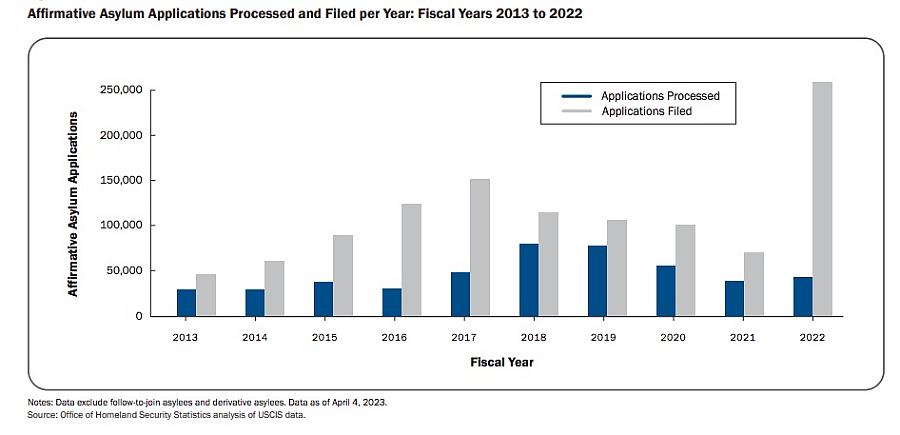

Issuance of a social security number and work permit can take up to two years, after which the cases disappear into the American immigration system’s overwhelming backlog for evaluations. According to UNHCR data, 63 out of 2,734 applications for asylum in 2023 received a final decision. The U.S. Department of Justice reported 97 decisions in fiscal year 2023 but did not post the number of applications.

USCIS data for affirmative asylum applications in 2023

It's a complicated situation where people can barely stay housed, even if they manage to earn beyond the income threshold eligibility for Medi-Cal. “You are too poor to buy insurance but you are too rich to be eligible for Medi-Cal,” Thein remarked.

Survival over preventative health

Individuals earning less than $47,520 a year can purchase their own insurance through the Covered California health insurance marketplace. But even if asylum seekers become aware of these services, they might go without.

The state of California is one of four states that levies penalties for lack of health coverage — 2.5% of the household’s annual income or $800, whichever is greater. But this threat is not enough of an incentive to make pinched asylum seekers pay out of pocket for coverage.

Asylum seekers from Myanmar are not alone in putting preventative health care last.

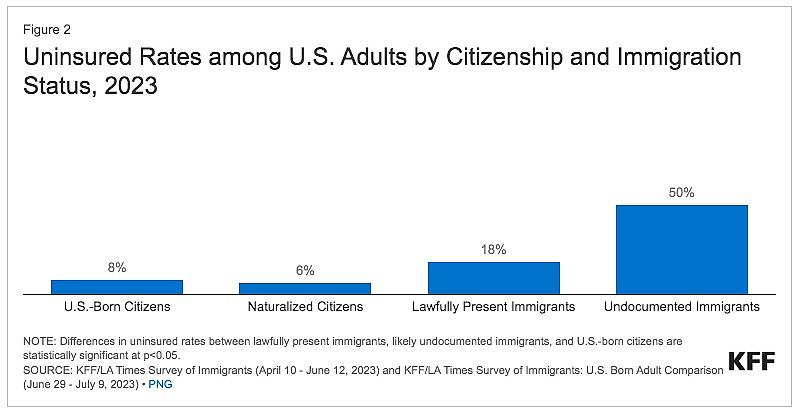

In 2023, Kaiser Family Foundation reported that 50% of all undocumented immigrants and 18% of lawfully present immigrants were uninsured, compared to 6% of naturalized citizens and 8% of U.S.-born citizens.

“It’s, ‘I need to get a job first, I need to get a room first,’ Also, they feel very healthy,” Thein explained.

He added that, the limited specialized, especially dental, coverage offered by low-income health plans further encourages people to take their chances. Why pay for so little in return?

Kaiser Family Foundation data on uninsured rates status

Zaw Phan, a member of the Kachin Indigenous minority in Myanmar, came to the U.S. with a student visa in 2008.

He worked at an immigrant health clinic serving new arrivals for the city and county of San Francisco for 15 years before moving to Sacramento to be able to purchase a house for his family.

In his work today as a medical assistant at a primary health care clinic for refugees, he observes that working refugees could scrape together the funds to invest in health services but simply do not do so.

“It’s necessary but it’s not mandatory — if it’s mandatory, the government will provide it for free,” he said.

He said that his clinic often loses contact with immigrants from Myanmar who receive work permits and gain the ability to make money.

“We don’t like chasing people — we only have certain attempts. First, a phone call. Then, a letter. Then, a home visit. Then, we close the case,” said Phan. These lost causes are a testament to the unmet health care needs in the community.

Under the bridge, under the radar

The Rev. Naw San of San Francisco Kachin Baptist Church said that most refugees from Myanmar who landed in Northern California left for more livable places like Indiana, Texas, Nebraska, or Florida. But asylum seekers keep coming.

As someone who helps immigrants, refugees, and asylum seekers get work and room shares, Thein has seen it all.

“Some kids are sleeping under the bridges now in Pacifica, and they would never tell their parents,” he said. “I did that, too, you know,” he added.

Thein came to the U.S. in 2011 as a refugee via Malaysia at age 25, right after release from compulsory military training in Myanmar. Most of the migrants sharing his journey had little education and had never dealt with financial institutions.

But he said he also arrived to “a different Oakland” 13 years ago, and that the housing market is far nastier today, presenting the greatest obstacle to survival.

From left to right: Zaw Rain, 26, Lawt Naw, 23, and Thae Su , 23 (no relation to Hazel Su), asylum seekers in Daly City. Only Su has limited medical insurance through a part-time job taking tickets at San Francisco International Airport. These are the faces of the current exodus from a country in turmoil.

Photo by Jia H. Jung

As refugees have left the Bay Area for wherever they can survive, their networks have become fractured and Bay Area organizations that used to serve them have changed their focus to other groups.

Jodi de la Peña VanderPol, board chair of Burma Refugee Families & Newcomers (BRFN), told AsAmNews that lack of funding is a significant barrier to continuing to serve asylum seekers from Myanmar or anywhere else.

“Most organizations rely on government funding and neither the feds, the state, nor the county fund the same type of support to asylum seekers,” she wrote.

While BRFN does not turn anyone down, the organization has publicly shifted toward serving refugees from Afghanistan and Eritrea, and is in formal proceedings to change its name to Bay Area Resource For Newcomers.

What are schools doing for student asylum seekers?

Su has dropped out of school since she could not afford another semester of international tuition and expenses.

Asylum seekers enter the U.S. after giving assurance that they can pay their way, and cannot identify themselves as refugees. Therefore, they miss out on support from the country, state, and county.

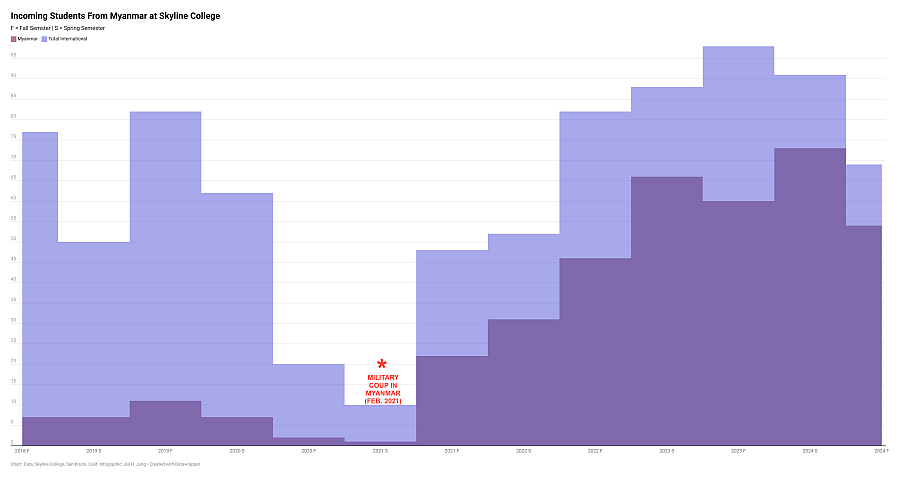

Cherie Colin, the Skyline’s director of community relations and marketing, shared that, since fall of 2021, 352 students from Myanmar have enrolled. Of that number, 274 are on record as having entered with a visa issued by Skyline College, seeking political asylum. Only 208 reported to campus.

The college declined to respond with data about retention rates for these students.

Incoming students from Myanmar at Skyline College

Colin said that in her 12 years at the college, she had never seen such an influx of a specific population of international students, much less one that is conflict-driven.

The school has responded with on-campus jobs that allow students from Myanmar to work 30 hours instead of the normal cap of 20. Students having trouble affording basics can get help buying groceries. The college also tries to help students find affordable housing and mental health resources.

“We realize that they need to make money and survive here somehow, right? And we want them to thrive, not just survive,” said Colin.

She said that students who were able to stay enrolled were motivated and active members of the school’s community.

Even when health care is a priority

Aye (Aylin) Myat Thu, 26, arrived in the Bay Area on July 29, 2023, and initiated her asylum application the next month.

She entered on a visitor's visa as a working adult with one week’s worth of clothing in her luggage while participating in a program as an international coordinator for Volunteers in Asia (VIA), a cross-cultural learning organization based in Palo Alto.

But while she was on a side trip to see distant relatives down in Los Angeles, she received notice that the company she worked for in Vietnam was dropping her after five years because it was closing its operations in her volatile home country of Myanmar.

As an award-winning activist and educator of students refusing to attend military-ruled schools in Myanmar, Thu felt afraid to go home even if she knew she could no longer live in Vietnam without her job. She decided to stay in the U.S.

With housing settled, but no steady income, she applied for Medi-Cal in July and recently got it.

“But I don’t know how to use it. I don’t know who to call or where to go,” she said. She wants to test her vision to see if she has to update her eyeglasses prescription and is unsure whether she can make a claim for the visit.

Thu tried to use California’s online health care interfaces when applying for insurance. While highly skilled in English and able to comprehend the health department’s online literature, she still had questions.

“There are so many resources here but we can’t know which one is best for us. Of course I go to those websites and they give the numbers. And I call the numbers and they don’t answer. It’s so frustrating. I get confused again, like, am I doing the right thing?” Thu said.

Thu had to take time off to walk into a health services office for help so she could complete the process correctly.

Responding to disaggregated needs

Thein works with asylum seekers like Thu who are aware of medical benefits and ask for his help to sign up.

He has to prioritize Alameda County inquiries. Hazel Su in Daly City and the bridge sleepers of Pacifica are across the bay in San Mateo County and not within his jurisdiction.

Thein, who works to inform Alameda County about the Burmese-speaking community, said that counties are often unsure whom to serve because they categorize migrants from Myanmar as “Burmese” if they disaggregate them from the greater “AANHPI” bloc at all.

Kachin refugees remaining in the Bay Area gather at an Oakland baptist church every Sunday afternoon.

Photo by Jia H. Jung

Thein pointed out that the group known as “Burmese” is further divided into a kaleidoscope of distinct ethnicities such as the Karen, and the less numerous Rohingya and Kachin. The Burmese ethnicity is just one of these groups, which all differ from one another in culture and language, with further intra-ethnic variance in class, education, faiths, and experiences.

Being himself of Rakhine ethnicity, Thein made it clear that “Burmese” refugees are hardly all ethnically Burmese, though all speak Burmese because of the dominance of the language in Myanmar.

“Like Ukrainian Russian-speakers, they don’t want to be called Russian,” Thein said, explaining how lack of seeing separate communities results in broadband neglect of the whole group classified as Burmese, adding that that since “the system doesn’t recognize them,” the problems of asylum seekers become invisible.

Little relief for psychological distress

Just as being unable to get by relegates physical health to the back burner, facing health problems while uninsured and dealing with competing stressors has a dramatic worsening impact on mental health, leading to a feedback loop of mind-body sickness.

A study published by the UCLA Center for Health Policy Research this year found that 45% of people facing housing insecurity experienced moderate to serious psychological distress.

Additionally, the American Psychiatric Association (APA) established that an average of one-third of refugees and asylum seekers attempting to resettle in high-income countries like the U.S. exhibit high rates of depression, anxiety, and post-traumatic stress disorders (PTSD), but that these rates can be up to 80% for some groups.

The APA recommended that mental health should be provided in partnership with social, cultural, and family support, and that clinicians could serve as advocates by linking refugees with avenues for housing, legal aid, health care access, education, and employment.

Hazel Su wasn’t aware of the mental health resources that might have been available to her. When her cohabitants urged her to seek help, she fortunately found someone in Yangon, Myanmar who offered video sessions from overseas.

Does the remote therapy help?

“A little,” she said.

No going back

Returning to Myanmar is not an option for asylum seekers because of the worsening civil warfare under oppression by the military junta government. And the ultimate priority for all asylum seekers is sending remittances to family, whom they sometimes solely support.

Thu’s parents, who oppose the military government, are in danger of persecution. Their small home restaurant business also flailed when the value of the kyat plummeted and inflation tripled.

“I just told them to stop everything, and that my brothers and I will support the family,” she said. Her plan is to reunite in the U.S. or Vietnam. “But it’s going to take a long time, I guess,” she said. While she waits, she volunteers her graphic design and marketing skills toward good causes while hoping she can parlay her talents toward consistent employment.

Hazel Su, who could be banned from returning to the U.S. for three years if she leaves the country because she overstayed her 180 grace period after losing her F-1 student status, is hanging on.

“When I’m not at work, I think of work. And when I come home from work, I think of work,” she told AsAmNews. “And the difficulty that I’m living with every day is that I’m the only one who can take care of my family,” she said.

Her brother needs the equivalent of $4,500 to flee to Thailand to avoid military conscription, which Thein says is a “death sentence” in the middle of the warfare in Myanmar.

She is waiting for her social security number and work permit could come through. “I can get paid like everybody’s getting paid,” she said.