Elevator Breakdowns in Cathay Manor — Chinatown's Senior Housing Project in LA — Is a Growing Safety Concern for Elderly Residents

The story was co-published with World Journal as part of the 2024 Ethnic Media Collaborative, Healing California.

A protest held in front of Cathay Manor in 2022.

Courtesy CCED

In 1988, on the streets of Chinatown in Los Angeles, about 200 Chinese seniors gathered in front of a 16-story modern building, holding up signs and protesting their living conditions. One of their primary concerns was the chronic failure of the two elevators in the building.

The protest was for Cathay Manor, a senior apartment complex with 270 units at the entrance of Chinatown, completed just five years prior. One protester interviewed at the time said that in her 50 years of living in Chinatown, this was the first time such a protest had occurred. "Chinese do not do this," she said.

Yet 36 years later, the seniors of this apartment continue to protest and lodge complaints.

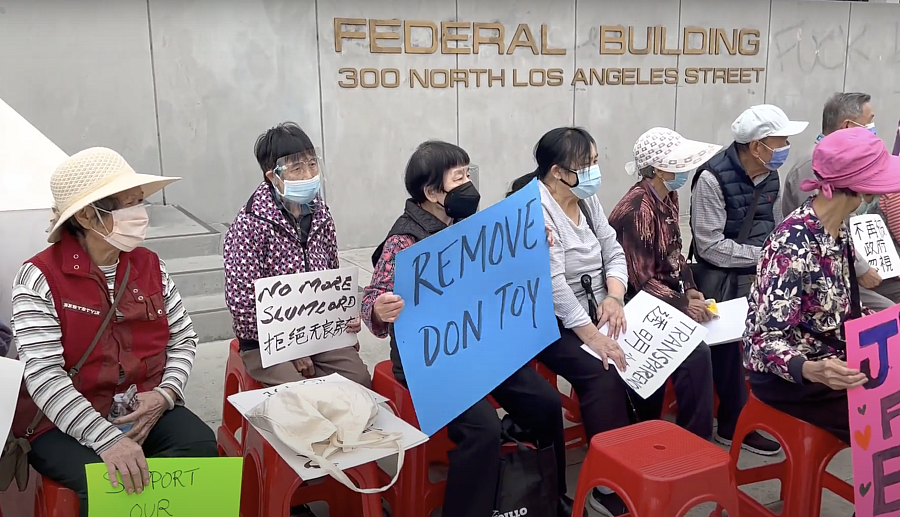

On October 27, 2022, over 30 residents marched to the Federal Building in Los Angeles.

Courtesy CCED

Although the faces and numbers of people have changed over the years, the issues plaguing the residents of Cathay Manor remain the same, including the malfunctioning of elevators.

The building is well-known in the Chinese community here. Once hailed as a “cultural beacon,” it is Chinatown’s first federally subsidized senior housing project. Funded primarily by the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, it caters to low-income elderly residents who, under the federal Section 8 program, pay only a third of their income in rent and utilities once they move in. During major Chinese festivals, officials and non-profit organizations visit here with food and essential living items to show care for the isolated elderly residents.

Yet, the two elevators have never functioned properly.

Cathay Manor, a senior apartment complex with 270 units at the entrance of Chinatown,

Jian Zhao, World Journal

Double Tragedy

Those elevators are one reason why C. Wu, 77, had to say goodbye to her husband of over 50 years at midnight on June 25, 2021.

Her husband, who had always been a sports lover and in good health, suddenly felt discomfort in his heart that night a little after 11p.m., Wu said. She immediately contacted their daughter who lived nearby and dialed 911. Within minutes, an ambulance arrived at Cathay Manor.

However, it wasn't until more than 20 minutes later that the medical personnel arrived at Wu's 12th-floor apartment. She recalls the time as "nearly 12 a.m."

During those 20 minutes, Wu felt her husband's heartbeat gradually weakening while she kept reassuring him that help was on the way. But it was too late. "He passed away in my arms," Wu said.

The barriers faced by the paramedics went beyond the elevators. Wu learned later that the iron gate at the entrance blocked the ambulance and their daughter from entering. Emergency responders had to climb over the gates and break the locks to allow the rescue team inside. Upon entering, they found the entrance door on the ground floor also tightly shut. No one responded to the call box. They tried to force it open but failed until a resident heard the commotion and came to open the door.

Once inside, the two elevators in the building were out of service.

Outside the iron gates of Cathay Manor

Jian Zhao, World Journal

The sudden death of Wu’s husband represented the second tragedy stemming from the building to befall her. A year earlier, she suffered a spinal fracture caused by an elevator malfunction—it had taken her from the 12th floor to the 16th floor, then rapidly plummeted to the first floor. "My teeth were loose and there was blood in the elevator," she recalled.

Wu immediately called her husband for help. He then pried open the elevator door and rescued her. However, since the elevators were out of service, her nearly 80-year-old husband had to carry Wu on his back to their 12th-floor apartment.

Since then, Wu has relied on painkillers to get through the day, but sometimes her back pain is so severe that she cannot move, and now her daughter is the only one who can take care of her. However, often, she chooses to suffer in silence. "My daughter also faces challenges in her own life," she said.

Isolated From the World

When she thinks about what happened to her, Wu cannot sleep. She doesn't know where to go for help or justice. She tried contacting the building’s owner (who is now the previous owner) but has yet to receive a response. " I’m old and I don’t understand English, who else can I ask?" she asked.

Wu says that her only hope now is Chinatown Community for Equitable Development (CCED), a local nonprofit established in 2016. CCED provides support to Chinatown residents in areas such as housing, employment, and culture. Since learning about the conditions in Cathay Manor in 2021, CCED has been advocating for the elderly residents and connecting them with public resources, becoming a lifeline for some residents.

"At first, residents didn't trust us and were unwilling to speak up," said King Cheung, one of CCED's founders. He explained that the residents are mostly low-income earners who cannot afford cars, and have lived in Chinatown for decades. They worked in restaurants and factories. Many do not speak English, and some do not even speak Mandarin, only dialects, making communication among themselves difficult. They also need help understanding the relevant laws and their rights as tenants.

According to a study and 5-year survey conducted by UCLA Asian American Studies Center, the median household income as reported for Chinatown is 2.87 times lower than Los Angeles county average level. Since the 2010s, a number of large mixed-use and multifamily residential developments have been completed, attracting mid- to high-income residents to Chinatown and its surrounding areas, mirroring trends seen in other neighborhoods near downtown Los Angeles. Even as the median household income increases, lower-income residents remain in the area.

Cheung also mentioned that many children of the residents have moved away from Chinatown. They occasionally return to visit during festivals and holidays or sometimes do not return at all. Due to cultural and educational differences, some older adults are not close to their children.

Protesting While Fighting Cancer

"But when the situation becomes intolerable, people can't take it anymore," Cheung said.

Both of the building’s two elevators were out of service for 22 days from Aug. 17 to Sept. 8, 2021. Less than a month later, from Oct. 14 to Nov. 6, they were inoperable for 23 days.

At the end of 2020, 85-year-old Wu Huirong, a resident of Cathy Manor, was diagnosed with a pancreatic tumor.; By the second half of 2021, it had doubled in size.

"When the elevator was out of order, it was very difficult to go for medical appointments, get medication, or buy groceries,” he said “Once, after climbing the stairs, my legs were weak, and I had to kneel directly on the stairs."

A resident living on the 10th floor mentioned that during elevator breakdowns, it took over an hour for some residents with limited mobility to go up or down the stairs once. Some elderly people, who had to use both hands to hold onto the railings, tied their personal belongings and groceries to their bodies by ropes while climbing the stairs.

These desperate situations have persisted for more than three decades.

On June 16, during my last interview with the residents, one elevator had just become operational again after a breakdown. Six senior residents had been trapped in the elevator for about 40 minutes. According to residents, elevator breakdowns occur approximately once or twice a month.

As one of the few residents with a university education in Cathay Manor, Huirong has become a prominent voice in the protests and demonstrations. Even after his tumor diagnosis, he has continued to participate. Despite undergoing a splenectomy related to his cancer, Wu Huirong still helps organize materials and writings. "I feel it's a responsibility, but I don’t expect everyone to do the same," he said. Some residents are deeply concerned about being evicted. Huirong waited six years on the Section 8 waiting list to move into Cathay Manor.

According to data from the real estate website Apartments.com, commercial apartments near Cathay Manor, studio apartments typically rent for over $2,200 per month. One-bedroom apartments in the area rent for around $2,700 per month.

Protesting, Marching and Speaking Out

On June 24, 2024, the residents voted for sending a “Request for Action” letter to City Attorney Hyde Feldstein Soto urging the acceleration of the criminal case against Don Toy and C.C.O.A..

Courtesy CCED

"People get tired because there's no results," Cheung said, referring to the lack of fixes and improvements in the building.

CCED tried to make change. They contacted the city, the department of Housing and Urban Development, Los Angeles County Department of Public Health, the FBI, and the police. Cheung said a city inspection once found 360 violations, including cockroach infestations, broken stoves, pipe burst, and more

Senior residents returned to the streets of Chinatown again, protesting, marching, and speaking out. On Oct. 27, 2022, over 30 residents aged in their 80s and 90s braved high temperatures to hold a march and press conference in front of the Federal Building in Los Angeles. Many of them even carried canes, sat in wheelchairs, or carried pill bottles. Given the limited mobility of many elderly protesters, volunteers prepared chairs and medical supplies in advance.

Many residents firmly believe that the previous owner Don Toy, the chief executive of the Chinese Committee on Aging (C.C.O.A.) Housing Corporation, a nonprofit that developed Cathay Manor with HUD's supportive housing program and Section 8 rental assistance, is the main culprit.

A sign in front of Cathay Manor

Jian Zhao, World Journal

Fred Nakamura, a tenant rights lawyer with over 40 years of experience who previously worked at Neighborhood Legal Services, provided legal assistance to the residents. On September 7, 2021, approximately 180 residents filed a lawsuit against C.C.O.A. alleging its failure to comply with the duty of maintaining operable elevators and other facilities. Additionally, there have been at least two criminal indictments against Don Toy.

On Aug. 12, 2024, another hearing on the motion of the case will be held in Los Angeles County Superior Court.

But over the past three years, several plaintiffs named in the lawsuit have passed away, and Nakamura also died a few months ago.

"Residents passed away or moved out. New residents keep moving in. Only the issues stay," Cheung remarked.

Dawn Breaks

The repeated protests and dangerous living conditions at Cathay Manor caught the attention of government officials. In October 2021, Los Angeles City Attorney Mike Feuer announced that his office had filed 16 misdemeanor charges against the building's owners, including Don Toy and C.C.O.A. Housing Corporation, for failing to maintain working elevators and other issues.

Since November 2021, U.S. Rep. Jimmy Gomez has been assisting residents by urging the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) to take action to address the housing conditions at the building. In 2022, residents also brought their concerns to Karen Bass, the city’s current mayor who was running for office at the time.

This year, some residents hold regular monthly meetings to collectively discuss solutions to address living condition issues, including problems with elevators and others.

There was a turning point last year when Cathay Manor was sold for $97 million. The new owner, privately held Capital Realty Group, operates approximately 17,130 affordable housing units across 27 states, according to CoStar. The residents are hoping for better management of the building.

Inside Cathay Manor. The building is undergoing renovations.

Jian Zhao, World Journal

The building is undergoing renovations, with old cabinets, appliances, and bathrooms being refurbished. Some residents have already moved into upgraded rooms. While some residents are encouraged, others point out new issues, such as the removal of the centralized alarm system at the bedside and inconvenient bathroom facilities.

Even so, the elevators still break down from time to time, leaving the older residents unable to move out of their apartments easily.

"This place isn't good enough; you're free to leave." Wu was once told. She then continued, "I don’t have the ability to buy a place to live. I have only myself to blame. "

This project is supported by the USC Annenberg Center for Health Journalism, and is part of “Healing California,” a yearlong reporting Ethnic Media Collaborative venture with print, online and broadcast outlets across California.