To Bakersfield cops, concern for opioids grows — but meth is still king

This story was produced as part of a larger project led by Kerry Klein, a participant in the USC Center for Health Journalism's 2018 Data Fellowship.

Other stories in this series include:

Kern County’s Opioid Users Lack Access To Much Needed Treatment

Four Years Sober, Recovering Heroin User Shifts Focus To Saving Other Lives

To Bakersfield Cops, Concern For Opioids Grows - But Meth Is Still King

Bakersfield police officers scour a motel room where they found a small amount of methamphetamine on a dresser.

KERRY KLEIN / VALLEY PUBLIC RADIO

Bakersfield Police Officer Jaime Orozco doesn’t have to venture far to find criminal activity—less than two miles from the police station, in fact, at the Plaza Motel on Union Ave. “These little hotels here, this is all infiltrated with a lot of drug use,” he says as he and his partner cruise past the bleached-white, single-story complex in their patrol car.

A group of people sit on folding chairs outside one of the rooms in the central parking lot. Orozco recognizes one of the men—he’s on parole—and as they drive past, one of the man’s buddies sees the patrol car and then gets up to put something inside the room. “I'm just going to talk to this kid. He's drinking a beer,” Orozco says, stopping the car and getting out.

He and his partner determine that one man was indeed drinking in public, and the guy on parole is the one renting the room—which means the officers can search it without a warrant. A few other men with them are on probation. Orozco radios for backup and four more officers arrive in minutes.

Among those is Officer Nathan Poteete, who pulls on sterile black gloves and scours the room with his partner, lifting the television and flipping the mattress. They find nothing out of the ordinary, until one of them picks up a cell phone case on a dresser to reveal a narrow line of white crystals. It’s almost like sugar. “There's some dope right there,” Poteete says. “That’s crystal” – as in methamphetamine.

While Poteete’s partner scrapes the crystals into an evidence bag, Poteete walks outside to the man on parole, who’s sitting on the curb with his buddies. Poteete reads him his rights, then starts grilling him. The man uses meth once a week and prefers to snort it, says he’s 30 years old but started using when he was 12.

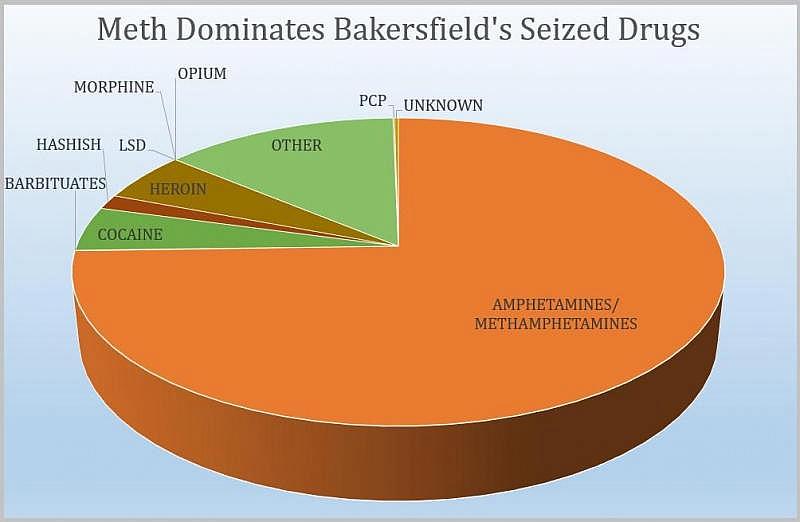

“If there were 100 people, how many would you think use meth, staying at this hotel?” Poteete asks. Probably 70, the man responds. Maybe 80. And that’s not a surprisingly high number to these cops. Meth’s a factor in around four of every 10 drug incidents in Bakersfield. It’s the most common reason patients seek drug treatment from the county.

The thing is, Poteete, Orozco and their partners aren’t narcotics officers—they’re in Bakersfield’s gang unit, looking to snuff out activity associated with the city’s Crips, Bakers and other criminal groups. And yet, during the day that I spend with their unit, one officer tells me he encounters drugs at least once every shift. Another jokingly claims he can throw a rock anywhere in the city and hit someone carrying drugs. “It's an origin,” Orozco says. “It almost all starts with narcotics.” And despite the chokehold heroin and pain pills have had on public health for years, Bakersfield cops are dealing with far more than opioids.

All drugs, excluding marijuana, seized by Bakersfield police from 2015 to 2018. Excludes drugs in liquid form, as pills or in other units other than solids measured by weight. (BAKERSFIELD POLICE DEPARTMENT)

After taking stock of the scene at the Plaza Motel, the officers handcuff the man on parole and take him to jail. But Jaime Orozco tells me he won’t be there for long, because he was only carrying the meth—not selling it. “That's the only time it ever becomes a felony anymore,” Orozco says.

Orozco has seen drug policing shift over time. He and his partner Christian Hernandez graduated from the academy together in late 2013, the year before Proposition 47 downgraded drug possession in most circumstances from a felony to a misdemeanor. Cops tell me this has led to more drugs on the street, which is difficult to confirm using drug seizure data from the Bakersfield Police Department, but is generally supported by data from the county sheriff’s office.

At the same time, Orozco says Prop 47 has had another surprising effect: Calmer interactions with suspects. When he first began patrolling in 2013, suspects would run, leading to pursuits and car chases. “It was crazy,” Orozco says. Now, however, “there's no real reason to run anymore. They know they're going to get out in a few hours. It'll just be like a 16-hour hold at the jail and then they'll be right back out.”

While the other officers book the suspect, Orozco and Hernandez head to the police property room and lab with his backpack. Orozco dumps out the candy and spare change from inside, catalogues it and secures it in a locker. “Because it's his personal property it gets booked in here,” he says. “When he gets released, it'll be in here for him.”

Meanwhile, Hernandez runs a test to identify the contraband. He scoops a minuscule sample of the crystals into a glass vial, stirs, and watches them turn orange. It’s officially methamphetamine. Hernandez seals the bag and hands it over as evidence. Eventually it’ll be destroyed.

Central California is a conduit for meth, a waypoint between producers in Mexico and their customers throughout the U.S. The drug is cheaper than it used to be, especially in California, and seizures at the border have been creeping up for years. That goes even for states in which drug possession hasn't been decriminalized.

But meth isn’t the only drug worrying law enforcement: There’s also fentanyl, a synthetic opioid some 50 times as potent as heroin. It’s so new to Bakersfield, cops there categorize it as “other” when logging it into police reports. “I think we’ve seen it only during search warrants,” says Orozco. Hernandez says he never has.

Fentanyl hasn’t yet devastated California the way it has the East Coast, but feds with the DEA and Customs and Border Patrol are seizing more and more of it throughout the country—much of it in deadly combination with other drugs.

But even if these officers had come across fentanyl, he’d have likely called in the narcotics team, which is trained to handle fentanyl carefully—sometimes in full-body hazmat suits. “A small dose, if we were to get into contact with that with no gloves or anything, it could be very lethal,” Hernandez says.

Thanks to opioids, some officers have even become impromptu health providers, administering the life-saving recovery drug Naloxone to users who’ve overdosed. Most Bakersfield cops don’t yet carry the drug, but the county sheriff’s office has used it at least 11 times since 2016.

Toward the end of the evening, I switch cars and ride with Officer Nathan Poteete and his partner, who go through the same rigmarole of booking suspects for dubious behavior while on parole. I ask Poteete if he feels at all like Sisyphus, the disgraced king of Greek mythology who gets sentenced to rolling a boulder uphill, again and again, for eternity. “Absolutely, you run into the same person who’s a problem over and over and over again,” Poteete says. “And unless they do something very serious, they’re not going to go to jail for their drug use, but they’re constantly causing issues.”

Then again, Poteete says, most people don’t last long using heavy drugs. Eventually they do disappear. And the cycle starts again.

[This story was originally published by Valley Public Radio.]