BL Special Report: HSD struggles with high suspension rates

This story was produced as part of a larger project led by Noe Magaña, a participant in the 2020 California Fellowship, investigating the social-emotional health of students in Hollister.

Read the other parts of this series here:

Part Three: BL Special Report: Students falling through the cracks

Marguerite Maze Middle School.

Photo by Noe Magaña.

This is the first in a three-part series about the social-emotional health of students in Hollister. This article was produced as a project for the USC Annenberg Center for Health Journalism’s 2020 California Fellowship.

Hollister School District’s special education department has earned a reputation in recent years for being dysfunctional and lacking qualified staff. And with COVID-19 distance learning now the norm for the foreseeable future, the challenges to serving this vulnerable population keep stacking up.

Suspension statistics for the district in the 2018-19 school year show schools grappling with the demands of special education, behavioral issues and timely and accurate assessments.

Independent consultant Marilyn Shepherd told BenitoLink on Sept. 8 that when she analyzed HSD special education referral data from the 2018 fall semester, students in general education with behavioral issues were referred without first receiving any interventions, violating special education law and adding workload to the already overwhelmed department.

“In looking at the information and data, there was no evidence that the general ed. staff were utilizing research-based strategies to address behavioral issues before referring to special ed.,” Shepherd said. “There are just so many that were being referred with little or no interventions before referring.”

Shepherd’s report said this was happening in part because of a lack of qualified staff such as board-certified behavior analysts, and a lack of staff trained to deal with behavioral issues and special education students.

HSD Superintendent Diego Ochoa, who was hired in January 2019, surely has his hands full. He told BenitoLink that when he came to the district, 90 students had not been evaluated or assigned an individual education plan. Over the last year and a half, Ochoa has hired more qualified and more Spanish-speaking staff in special education, and community relations have improved. But judging by suspension rates, Ochoa has some big challenges ahead.

- Hollister School District suspension rates continue to be high at 4.8%, compared to the state average at 3.6%.

- In the 2018-19 school year, almost one in every six Marguerite Maze Middle School students in Hollister was suspended at least once, according to the California Department of Education.

- About 75% of the HSD suspensions were associated with violent behavior or weapons.

Statewide, suspension rates in public schools are being examined more closely as district boards work to tackle low student performance and disrupt what is known as the “school-to-prison pipeline.” This refers to statistics that show students who are suspended have higher dropout rates and are significantly more likely to be involved in the juvenile and adult justice systems.

Local nonprofit Youth Alliance, in partnership with the San Benito County Office of Education, held a workshop on the pipeline in 2019 that focused on how relationships and positive feedback can help students stay in school.

Also in 2019, laws were passed aiming to reduce suspensions, based on studies showing that the overuse of suspensions can contribute to the state’s achievement gap. In September 2019 Gov. Gavin Newsom signed SB 419, which prohibits elementary and middle school teachers from suspending students for disrupting school activities or defying school authorities. The bill went into effect in July.

Now, only principals and superintendents have the authority to suspend students for violations such as causing, attempting to cause, or threatening to cause physical injury to another person; possession of weapons, alcohol or drugs; or committing an obscene act or sexual assault.

Shepherd said the law forces districts to be proactive with respect to training teachers and staff on how to deal with student misbehavior. Because most of the misbehavior occurs on playgrounds, she said all staff need to be trained.

“It’s a hard conversation, it’s a hard subject sometimes for people to grasp and/or want to deal with,” Shepherd said. “Nobody wants to deal with a challenging child or student.”

More recently, HSD, citing budget cuts, put more distance between its students and law enforcement by cutting its school resource officer program. The program was implemented in the 2018-19 school year.

Data also shows referring students to special education is not improving school as a learning environment. According to the California Department of Education, 24% of students suspended in the 2018-19 school year were diagnosed with a disability, even though disabled students make up only 13% of the student population. However, not all students diagnosed with a disability are receiving special education services.

Ochoa said in the 2018-19 school year, 9.2% of special education students were suspended. That’s more than double the suspension rate of students with no disabilities (4.3%).

In the same year, special education students comprised 11.4% of the enrollment, but they comprised 21.9% of all suspended students.

Statewide, not only do suspensions disproportionately affect students with disabilities, but according to studies, students in minority groups, particularly Black students, are more likely to be suspended than white students for the same recurring violations.

And while data shows that is not the case in HSD, whose enrollment has increased from 75% to 80% Hispanic students since the 2011-12 school year, there are cases in which parents see unequal treatment for students in minority groups.

Nora Vazquez recalls her youngest son, Alejandro, 11, being bullied by white students when he was in second and third grade at Hollister Dual Language Academy. She said the school didn’t discipline the other students through suspensions.

“Fue mordida, hubo sangre, hubo todo,” Vazquez said. “Y no hicieron nada en la escuela.” (“There was biting, there was blood, there was everything. And the school didn’t do anything.”)

For less serious misbehavior, Vazquez said her eldest son, Jose De Jesus, 16, was suspended from Hollister Dual Language Academy for three days when he was in fifth grade for being a distraction to the classroom by loudly striking his pencil to his desk.

Jose De Jesus and Nora Vazquez. Photo by Noe Magaña.

At the time De Jesus was not in special education, despite a years-long effort by Vazquez to put him there. Vazquez said De Jesus was diagnosed with agenesis of the corpus callosum, which occurs when nerve fibers of the two cerebral hemispheres do not develop properly. Vazquez said her son sometimes experiences anxiety.

“Considero que fue muy excesivo el castigo para mi hijo,” Vazquez said. (“I believe my son’s punishment was too excessive.”)

Although Spanish is spoken in 46% of Hollister’s households, the district has historically not employed enough Spanish-speaking teachers and staff.

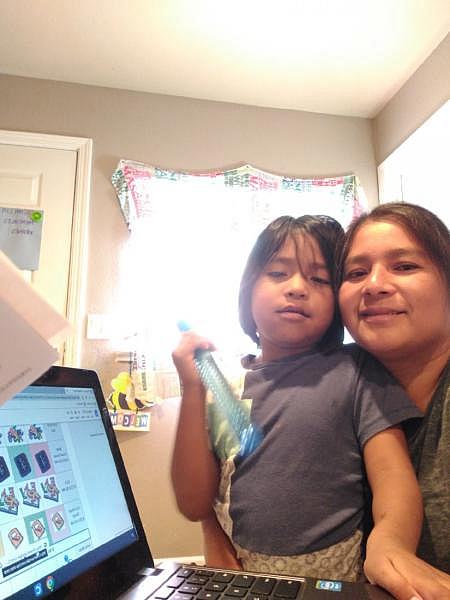

Belen Gonzalez, mother of five-year-old Henry, said her problems with the district have not been in attaining services for her autistic son, but in dealing with district office staff. She said when she asked for guidance on how to obtain affordable internet access for distance learning when school sites were closed last year, there were only a few staff who spoke Spanish. She said those who did speak it were unwilling to help with her requests.

Belen Gonazalez with her son Henry. Photo courtesy of Belen Gonzalez.

Gonzalez said Timi King, Henry’s former teacher who only speaks English, went above and beyond to support her and her son. She said King dropped off Henry’s schoolwork during shelter-in-place and communicated with her in Spanish through texts asking how else she could be of service.

King also sent Gonzalez pictures of Henry during school trips to reassure her he was having fun.

Gonzalez describes herself as a mother who struggles to let Henry be without her supervision—to the point that if she could not chaperone him during field trips, Henry would not be allowed to go. King’s pictures gave her peace of mind.

“Es algo que no lo hace cualquiera y yo valoro mucho lo que ella ha hecho,” Gonzalez said. (“Not just anybody does this and I value what she has done a lot.”)

Ochoa has doubled the number of district psychologists working for HSD, including four who are bilingual. He also hired more Spanish-speaking staff, which has benefited both student and parent communication. But he and HSD have not been able to reduce suspensions. The suspension rate has increased over the past two years and is now up to almost 5%.

Surrounding districts are also struggling with suspension rates, including Morgan Hill Unified and Pajaro Valley Unified. They have seen suspensions rise in the last two years to 5% and 4.7%, respectively. Though Gilroy Unified decreased its suspension rate by 0.4% to 5.1% compared to the 2017-18 school year, it’s still higher than the state average of 3.5%.

For Vazquez, who feels her son De Jesus lost learning opportunities with previous administrations, the most important change Ochoa has made was including parents in the conversations.

“Me ha gustado mucho sus propuestas y todo lo que él trae para todo el distrito,” Vazquez said. (“I really like his proposals and everything he brings to the district.”)

She said Ochoa has also asked for input from parents on how they would like to see the budget utilized and what services are most needed.

Assistant Superintendent of Human Resources Erika Sanchez said the district hired 11 Spanish-speaking special education staff and four in the general education departments for the 2019-20 school year.

“Lo principal es que él está abierto,” Vazquez said. “Nos ha escuchado, ha tratado de resolver algunos de los conflictos que se tienen.” (“The main thing is that he is open. He listens to us, he tries to resolve some of the conflicts that come up.”)

[This story was originally published by BenitoLink.]