Black children die at alarming rate in Sacramento County, and here’s why

This article was produced as a project for the 2015 California Data Fellowship, a program of the USC Center for Health Journalism.

Other stories in the series include:

City of Sacramento joins efforts to prevent black children’s deaths

Debra Cummings is a vocal advocate for expanding youth activities in Del Paso Heights. She and other neighborhood leaders are integral to Sacramento County’s new effort to reduce black child deaths. “I will not sit here another day and comfort another husband or mother who has lost their child when there’s something I could have done,” she said. Lezlie Sterling lsterling@sacbee.com

Paris Dye teared up, thinking back on how many Sundays she has spent consoling grieving mothers at Liberty Towers Church, a Christian ministry in an industrial section north of downtown Sacramento.

Dye is programs director at the church, a role that involves reaching out to families and helping them integrate into the congregation. Not infrequently, that means sitting with women who have lost children, sometimes related to violence or drugs, more often to illness or complications at birth.

She can still feel the cries of Donna Green, whose teenaged son Jacob was gunned down four years ago in Foothill Farms, just blocks from the church. He was shot in the stomach on the night of his 18th birthday after he got into a fight with another young man in the neighborhood.

“The worst scream I ever heard was his mother,” said Dye, who raised three boys of her own in the Foothill Farms neighborhood. “When they closed the coffin on that kid, it was the most painful cry. I can’t shake it. I don’t ever want to hear it again.”

Early death is a fact of life in Sacramento County’s poorest, most isolated neighborhoods. It snares teenagers driving home with friends from high school football games. It takes newborns sharing a bed with parents and siblings. It silences heartbeats in stillborn babies who never see light. And with greater frequency than any other racial group, it takes African American children.

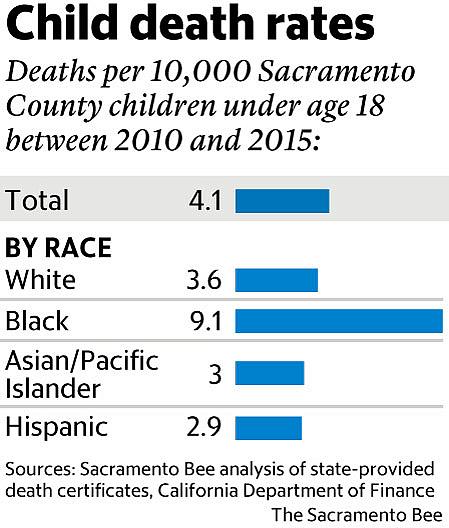

Between 2010 and 2015, African American children died at well above the rates of any other racial or ethnic group in Sacramento County: Nearly one-quarter of the 873 children under age 18 who died in the county during that six-year time frame were black, even as black youths made up just 11 percent of the population in that age group.

During that time period, the death rate among black children was more than twice the rate of white children and about three times the rate for Latino and Asian children, according to a Sacramento Bee review of state death certificates. A similar death rate for black children exists at a nationwide level, but Sacramento County’s rate is significantly higher than California’s.

“I’ve yet to be presented with another challenge in front of us as a local government that deserves our attention more than this,” said Phil Serna, a Sacramento County supervisor whose district includes several high-risk neighborhoods for black youth, including Del Paso Heights and Oak Park.

“When the thing you are measuring is whether or not a certain group of your constituents is less likely to see their 10th birthday than another group because of their ethnicity or their ZIP code, it’s so unacceptable, it feels silly to even have to say it,” he said.

The issue is long-standing in Sacramento County and was highlighted in a 2012 report from the county’s Child Death Review Team. That report, based on an array of public documents, found that the black child mortality rate persistently outpaced that of other racial and ethnic groups from 1990 to 2009, and it cited four primary causes: perinatal conditions, including low birth weight, congenital infections and premature birth; infant sleep-related incidents, including sudden infant death syndrome; death from child abuse and neglect committed by parents or other caregivers; and violence committed by people other than the primary caregivers.

The Bee’s review found that pattern has continued: Of the 207 black children who died between 2010 and 2015, 38 percent of the deaths were linked to perinatal conditions; 18 percent died from sudden infant death syndrome and other sleep-related episodes; and homicides accounted for 8 percent of deaths. The remaining deaths were tied to accidents, suicides or natural causes.

The review also found ZIP code did indeed make a difference. The highest death rate for black children in the county was centered in the 95841 ZIP code, a neighborhood adjacent to Interstate 80, sandwiched between Carmichael and Foothill Farms. African American children there died at a rate six times higher than the countywide average for all children between 2010 and 2015.

Next in line were the communities of Foothill Farms, Del Paso Heights and the 95821 ZIP code in northern Arden Arcade.

Last month, after lengthy debate and analysis, county officials launched a massive and novel effort that aims to bring down those numbers. The plan is to spend $26 million in county funds and grants over the next five years to bolster the ranks of social workers, law enforcement, health providers, community organizers and others working with at-risk children in selected neighborhoods across the city.

Dubbed the Steering Committee on Reduction of African American Child Deaths, the idea is to expand existing programs and also involve neighborhood leaders, who will fan out through the community connecting people to services. The goal is to reduce black child mortality by somewhere from 10 percent to 20 percent by 2020.

The effort will rely on people such as Debra Cummings, a Del Paso Heights mother who has been a vocal advocate for expanding youth activities in her community. Cummings is part of a cadre of activists on the steering committee who will work directly with county representatives to identify specific neighborhood needs and get them addressed.

“It’s my duty to protect my babies,” Cummings told Sacramento City Council members during a meeting at which they voted to contribute $750,000 to the countywide project. “I will not sit here another day and comfort another husband or mother who has lost their child when there’s something I could have done.”

When the bear comes home

For many of those involved in the project, one of the more surprising aspects of the crisis are the sheer numbers of African American children in Sacramento County who are dying in the womb or in their first weeks of life. Between 2010 and 2015, more than a third of black child deaths in the county were attributed to perinatal conditions.

Berry Accius, a black youth mentor at the South Sacramento Christian Center Church, said he has been so focused on gun violence for the last two decades that he did not realize how many babies his community was losing.

“That was literally the most shocking one,” he said. “You assume people know how to take care of their babies at that stage ... but then you kind of realize that with the conditions we have in our neighborhood, we should expect things like this to happen.

“When you have poverty-stricken communities, and those people that don’t have the information, the knowledge, or the resources, how do you expect individuals to know how to take care of themselves or a baby?”

Experts cite a range of factors related to infant mortality that could affect African Americans disproportionately compared with other racial and ethnic groups. These include medical issues, such as relatively high rates of diabetes and obesity, as well as risk factors such as drug or alcohol use during pregnancy. But they also cite less tangible influences involving broken families, missing support networks, the everyday stresses of living amid poverty and violence and other legacies of discrimination.

About 29 percent of Sacramento County’s black residents lived in poverty during 2014, much higher than the 17 percent poverty rate for all other racial groups, census figures show.

Monique Jordan can speak to some of those stresses. Now 30, Jordan said she came from a troubled family and spent much of her childhood in foster care. She never felt loved, she said, and ached to start her own family so she would not feel so alone.

She had her first child at 19, but that stable family she craved never quite took shape. Her boyfriend, she said, was in and out of jail for drug trafficking and other crimes. During her first pregnancy, she was jobless, carless and had no parents to help out financially or school her on being a mother. She didn’t start receiving prenatal care until more than five months into her pregnancy, as opposed to the recommended first trimester.

In the ensuing years, the boyfriend came and went, often amid ugly arguments. Still, she found it hard to completely cut him loose. Over time, they married and had four more children. She raised them largely with the help of food stamps and other government assistance.

That meant living in a mold-infested home in Citrus Heights and then a Foothill Farms apartment where sleep frequently was interrupted by the cries of her children and the echo of gunshots outside. She kept her babies in bed with her, which she didn’t consider dangerous at the time.

Looking back, she thinks those stresses had an impact. Her sixth pregnancy ended in a stillbirth. Over the next two years, she lost another boy and a set of twins to premature delivery.

“I can’t buy them shoes. I can’t hold them. But I still celebrate their birthdays,” Jordan said, cradling her youngest son, 5-month-old Matthias. “It had something to do with stress, and my lack of knowledge of knowing the signs to look out for. That’s why I lost my children. ... I stressed instead of asking for help.”

Dr. Olivia Kasirye, Sacramento’s public health officer, is one of several experts interviewed who believe the black child death rates in Sacramento County are an outgrowth, in part, of stressful environments.

She cited a basic immune system response that is well documented: Fear – whether of violence, unemployment, hunger or eviction – puts mothers’ bodies into a “fight or flight” mode, she said. That moves blood to the muscles and away from the immune system, leaving a fetus susceptible to infection. Stress also causes blood vessels to constrict, including those in the placenta, depleting the supply of nutrients and oxygen to the fetus. That, in turn, can contribute to low birth weight and respiratory problems.

“When you see a bear, there is a reaction you get where the blood rushes to the muscles,” she said. “In those instances, it’s very useful. You get away from that situation, and everything comes down, and all the hormones go back to the level they’re supposed to be at. But what happens if that bear comes home every night?

“You’re being faced with this kind of stimulation on a day-to-day basis, and you can imagine, if it’s happening over a whole lifetime, that changes the whole balance of the body.”

A legacy of isolation

RoLanda Wilkins, who runs a south Sacramento nonprofit agency aimed at empowering young black women, sees broader cultural issues at work. Her nonprofit, Earth Mama Healing, offers field trips, workshops and other self-esteem-building activities to young black women across the area.

Many of the women she works with are dealing with unresolved mental stress brought on by traumatic childhoods, she said. Some feel alone and unsupported in their pregnancies.

She speaks from painful personal experience.

She and her partner conceived a child six years ago. Wilkins was 38 and working at The Birthing Project, a Sacramento group that connects women of color to pregnancy services. She knew that her diabetes, combined with her age, put her at risk. So did her intense workload – over 60 hours a week – which she maintained during her pregnancy so as not to place financial stress on her family or partner.

Five months into her pregnancy, she miscarried.

It wasn’t the first loss in Wilkins’ family. Her mother had two miscarriages, and her grandmother lost three babies before or shortly after birth, she said.

She sees a connection, rooted in the black American experience. Many black women think they have to be self-sufficient, that they can’t count on anyone else for help, Wilkins said. Friends and family don’t tell pregnant women to rest or may even criticize them for getting pregnant in the first place.

“It’s kind of long gone where somebody tells you to have a seat, or celebrate that you’re pregnant,” Wilkins said. “The first thing we think about is if we’re going to have money. A lot of these young girls are still trying to work when they’re six, seven months pregnant.

“When I was pregnant with my daughter I was working so hard – it was my culture. That’s how we do it in our family. You don’t want to be perceived as being lazy.”

Tyan Parker Dominguez, a University of Southern California researcher who studies racial disparities in infant mortality, agreed that cultural mores play a role. While poverty is a factor in infant deaths, she said, it’s clearly not the only one.

She noted that Latina mothers living in poverty have a far lower infant mortality rate than black women. She thinks that’s because many Latinas enjoy cross-border, tightknit families who see the arrival of a new child as a joyous event to be celebrated by the extended family.

Black women of all economic classes suffer higher infant mortality rates than women of other races and ethnicities at comparable income and education levels, Parker Dominguez said.

“If you grew up in a country where everybody looks like you – the people in power, the people who are rich – that’s a different way to think about yourself and your place in the world,” she said. “You don’t have the same concerns about your child being mistreated, of your son being shot outside your home. That’s not part of your reality.”

Black women, on the other hand, still suffer from a legacy of racism that has fractured American society, she said.

“Cultural messages, social policies, limited access to opportunities and mobility – all these things in your environment communicating to you that you’re not wanted, that you don’t have the same potential,” she said. “There’s also a sense that their babies are not as valued, that people don’t care about black kids.”

Trusted messengers

So what’s the answer? County services such as home health checkups, safe sleep workshops and family conflict counseling have been available for years, and yet the high black mortality rates persist. What is the county doing wrong?

That’s the question county leaders took to neighborhood groups in the months after releasing their 20-year review of child death rates. They were told the families and communities that need those county services the most often have no inkling they exist. County agencies operated in silos, disconnected from the nonprofit groups that know who needs help and how to deliver aid.

Under the new plan, grass-roots community groups will be able to add staff, expand capacity and fast-track struggling families into county programs that in the past would have taken months to reach.

“Before, we’d try to help people in the community, and our hands would be tied, and all we could do was offer a prayer,” said Dye, the programs director at Liberty Towers.

Kenya Franklin, a mentor with Black Mothers United, became a lifeline for Monique Jordan and her family, helping with medical visits, groceries and housing. Sacramento County is looking to expand on such programs as part of a broader effort to lower black child mortality rates. Lezlie Sterling lsterling@sacbee.com

“We’ve always been on the outside, doing what we can with our own resources to do our part. When they did the report, it was refreshing to know that people were actually watching. It gave us hope.”

Liberty Towers is one of seven community programs slated to get $120,000 annually over the next three years as part of the county outreach. Another is Sacramento Building Healthy Communities, a Sacramento nonprofit that partners with a range of programs, including Black Mothers United, which pairs black mothers in stress with a mentor and advocate.

Monique Jordan connected with the group after becoming pregnant with her youngest child, Matthias. Her mentor, 26-year-old Kenya Franklin, became a lifeline during and after Jordan’s pregnancy.

She took Jordan to her doctor’s appointments and out for groceries. She welcomed Jordan’s texts and phone calls when she needed to let off steam about some holdup in public services or the latest episode with the father of her children. She helped the family find a three-bedroom house in south Sacramento, which they moved into last month.

“Being a single mother, doing most of this by yourself, you don’t get many people, especially in 2016, asking what you need help with,” Jordan said. “Nobody does that.”

That personal touch is key to the county steering committee’s plan. Over the next year, it will send “trusted messengers” such as Franklin into people’s homes, schools and churches to help make moms feel safer and more supported, as well as connect families to the services they need.

“There are those people, the ‘grandmas’ of the housing complex – people everyone knows and trusts,” said committee member Gina Roberson, who worked for eight years at the county’s Child Abuse Prevention Center.

“If we can get those people talking about this, we can create that web and get the resources out. Imagine if we had a whole network of those people?”

[This story was originally published by The Sacramento Bee.]