Black Women Are Losing Access to Maternity Care. This Law Is Partly to Blame.

The story was originally published in CapitalB with support from the USC Annenberg Center for Health Journalism’s 2022 National Fellowship.

The health care system has disinvested in Georgia’s rural Black communities at disproportionately high rates. Since 1994, 41 labor and delivery units have shut down across the state.

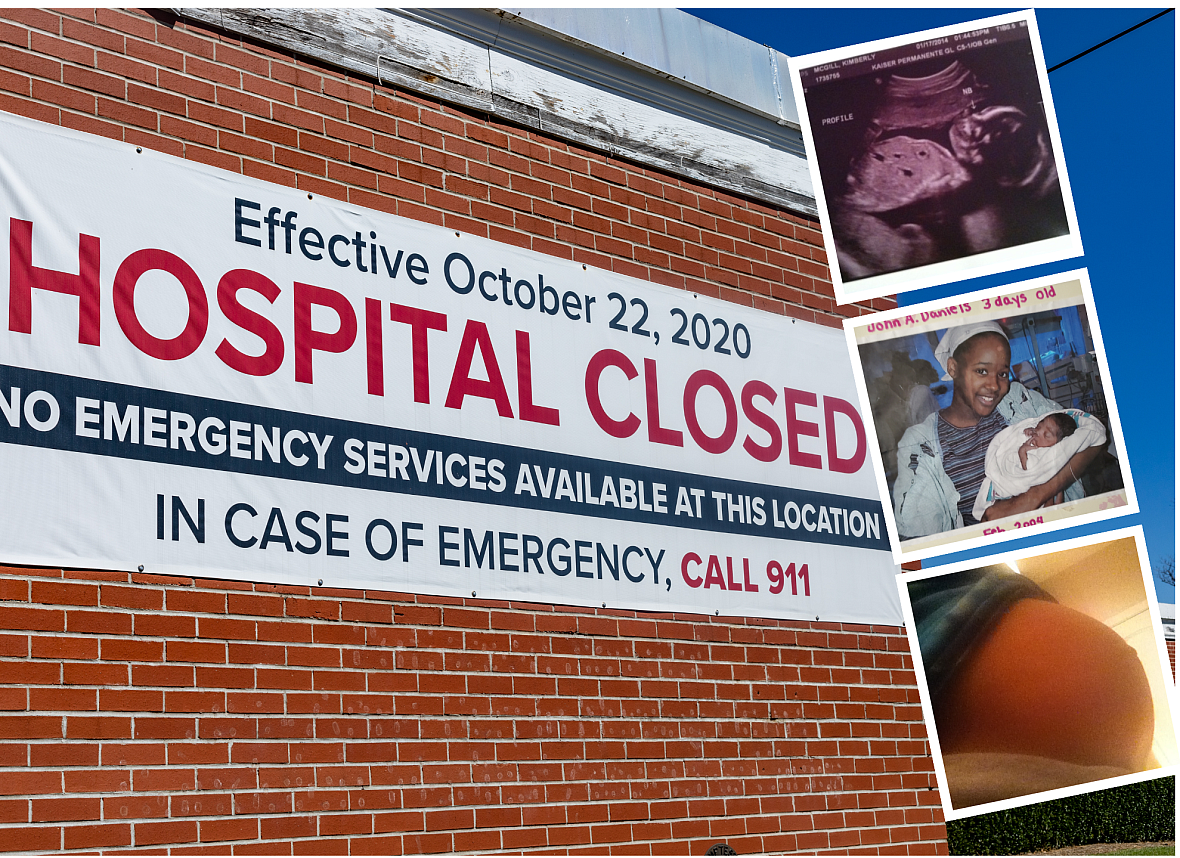

(Photo illustration/Eric Cash)

Capital B’s “Dangerous Deliveries” investigation examines the uneven distribution of maternal care deserts and poor birth outcomes in Georgia, one of the most dangerous states for childbirth. Read the full project here.

CUTHBERT, Ga. — Shayanna Alford called 911 when her water broke.

She lives in this quiet town of 3,000 people, tucked in the state’s southwest region. It has no hospital or obstetric care. The county’s ambulance service has also dwindled. The trucks are now dispatched from neighboring towns when the two they have are busy.

On that July morning, Alford waited while in labor for an ambulance that was 45 miles away. Once the driver hit the city limits, she waited another half hour for him to find the house. His confusion resonated through the phone.

“I’m not from down here,” he said. “It’s not my fault.”

Once they found her, it took another 45 minutes — cruising past the flower farms, Dollar Generals, Baptist churches and hand-painted “fresh peaches” signs that line Georgia’s country roads — to get to the nearest hospital, in Albany.

If her childbirth had come two decades prior, Alford likely would have welcomed her baby girl down the street at Southwest Georgia Regional Medical Center. But the facility, formerly known as Patterson Hospital, closed in the fall of 2020, even as the coronavirus pandemic thrived. Years earlier, its labor and delivery unit had shut down.

The hospital’s story is similar to many others. When they face financial hardship, labor and delivery units — which often do not bring in a lot of profit — are often first to be closed. Since 1994, 41 labor and delivery units have shut down across the state. And when they did, Black mothers often suffered most.

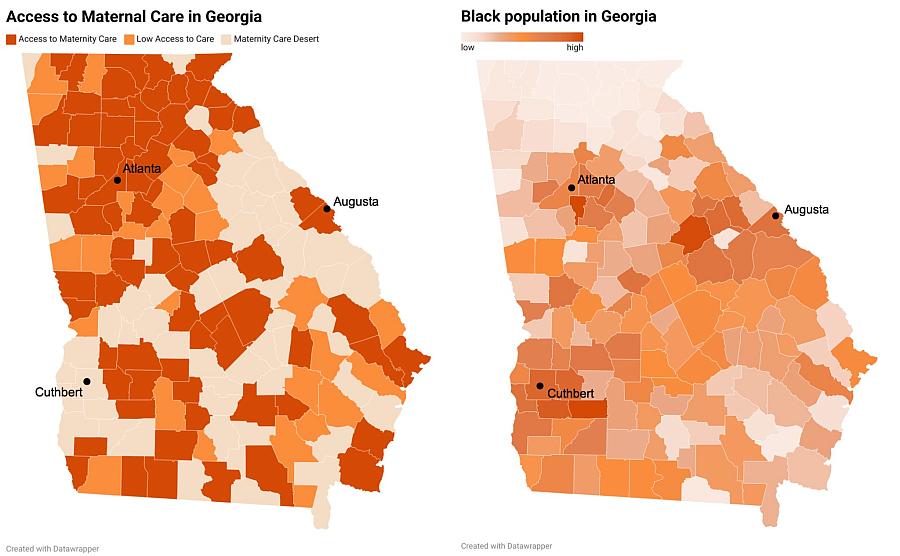

The health care system has disinvested in Georgia’s rural Black communities at disproportionately high rates, forcing families to travel dozens of miles and across state lines to receive critical care. Many of the state’s poorest regions battle the greatest barriers to health care, and face the worst outcomes.

A Capital B analysis of data from Georgia’s Obstetrical and Gynecological Society found that, since 1994, more labor and delivery units have been closed in Black counties than in white counties. Over the same period, twice the number of labor and delivery units have opened in white counties compared with Black rural counties.

Randolph County, where Cuthbert is located, sits in America’s Black Belt, a region known for its racist history and high poverty rates. The county, encompassing 430 square miles, has no birth centers, obstetric providers, or hospitals providing labor and delivery services. It’s a maternity care desert, a scarcity that bleeds into poor birth outcomes, including more emergency deliveries and preterm births. Randolph County’s birth outcomes are among the worst in Georgia.

The rate of preterm births and low birth-weight babies are higher in Georgia counties that have an above average share of Black residents (greater than 32%). Across the state, nearly half of those Black counties are maternity care deserts. By comparison, less than a third of majority white counties are maternity care deserts.

“Racism has always been pervasive in the state of Georgia,” said Natalie Hernandez, the executive director for the Morehouse School of Medicine’s Center for Maternal Health Equity. “We have significant Black populations in rural communities, and they’re suffering.”

Georgia’s maternity care deserts are mostly congregated in the state’s Black Belt, the largely rural, southern counties with high concentrations of Black residents. Source: March of Dimes (left) and the U.S. Census Bureau (right)

The prevalence of care deserts in Georgia is among the reasons the state is one of the most dangerous in which to give birth. The state’s maternal mortality rates are so high that they rank worst among other high-income countries.

Despite advancements in medicine and technology, racial disparities in who dies and who suffers the worst complications have persisted for decades. Black women make up most of Georgia’s maternal deaths. They are also nearly twice as likely as white women to experience life-threatening complications as a result of childbirth, such as hemorrhage, infection, and cardiac issues.

As providers attempt to fill the voids that produce poor birth outcomes in rural Georgia, they are having to fight against a bureaucratic state regulatory system that can work against them.

The state’s “certificate of need” system is at the center of the process that determines which communities get new health care resources. Proposed hospitals, labor and delivery units, or birth centers must prove to state regulators that the service is necessary through a certificate of need application, a process so burdensome that some providers drop out before completing it.

The certificate of need model has been criticized nationwide for creating hurdles that stifle newcomers to the market. Some states have repealed their certificate of need laws since the 1980s — but despite efforts to reform the model in Georgia, that state’s law remains.

Among the 35 states and Washington, D.C., that still have certificate of need programs, Georgia’s is one of the most restrictive. It allows existing hospitals to file objections to applications, giving the politically powerful industry tremendous influence in blocking potential competitors.

While a lengthy process regulates what medical facilities can open where, the state makes it much simpler to close them. With 30 days notice to the state, a provider can quickly shut a medical facility down, no government approval needed. Community need isn’t formally considered during closures. The decision to close hospital doors is often solely financial, putting rural and low-income communities at a severe disadvantage.

It is a failure in Georgia’s health care system: implement a demanding process to open new health care facilities, institute few regulations around when facilities shut down, and let Black communities suffer the most extreme consequences.

When Alford’s daughter was born prematurely, doctors failed to treat the newborn’s jaundice before releasing the family. After delivery, the new pediatrician said the baby should have been kept a few extra days for light treatments. Now, they would have to come into the doctor’s office, 30 minutes away and across state lines, each week for treatment.

Alford was confused and in tears. She had traveled all that way to deliver her daughter, yet wondered if the hospital’s delivery team had rushed their care. “Why didn’t they tell me that?” she said of her daughter’s jaundice diagnosis.

Alford’s voice grew hot, filled with anger, as she recounted the memory to a handful of community members who had gathered to talk about the community’s lack of medical care. As they sat around a platter of sandwiches, chocolate chip cookies, and a stack of potato chip bags, the neighbors lamented being abandoned when the town’s hospital shut down.

Alford’s premature birth could be related to the limited health care access in Cuthbert, experts said, given that comprehensive health evaluations and services require extensive travel. There’s a local clinic in town, but “the only thing they can provide for is about a cold,” Alford said.

“The system itself is doing what it’s intended to do,” said Brandie Bishop, an Atlanta-based birth and postpartum doula. “We built the system in a way in which Black women were always going to die.”

The fight for Augusta Birth Center

Katie Chubb curated an 821-page certificate of need application that detailed how a freestanding birth center would benefit the Augusta, Georgia, region. The application checked nearly all the boxes when she submitted it in the summer of 2021. She laid out the project’s costs and long-term finance strategy. She plotted the organization’s structure, staffed with nurses, midwives, and a physician. The center would serve 11 Georgia counties, with a focus on Richmond County, a majority-Black area bordering South Carolina.

Chubb projected that the Augusta Birth Center would deliver 240 babies in its first year. By year two, that number would nearly double.

She wants to be a care option for the increasing number of families looking to give birth outside of hospitals, where labor is often met with unnecessary medical interventions. Growing awareness of childbirth’s racial disparities has pushed some Black women to seek alternatives to hospital deliveries, including home births and birthing centers, though the centers have been known to exclude low-income patients due to high out-of-pocket costs.

Augusta’s three hospitals and many obstetricians prevent it from being a maternity care desert, but in a region known for its sharp racial divides, being poor and Black limits safe options for many pregnant residents there.

Nearly 60% of Richmond’s residents are Black. The median household income is just above $46,000, and more than 20% of its residents live in poverty. Its rate of low birth weight and preterm births outranks half of Georgia’s 159 counties. Next door, majority-white Columbia County has a median income nearly double that of Richmond, and it ranks among the 30 best counties in the state for birth outcomes.

Like all other certificate of need applications, Chubb’s was evaluated by two review analysts in the Georgia Office of Health Planning. Those analysts provide a recommendation on whether to approve or deny new projects. The office’s executive director and legal services officer make the final decision.

If denied, applicants can submit an appeal to a panel of four men, all lawyers appointed by Republican Gov. Brian Kemp.

The application requires detailed description of a project, including estimated costs, organizational structure, licenses and permits, construction plans, and zoning information. It also requires proof that the project is adequately financed. Providers can include maps of service areas, data on service utilization rates, and cite magazine articles and research papers that support their case for need. Applicants are charged with demonstrating that there are enough patients who will use the service without taking customers from existing facilities.

The projects must meet “minimum quality standards” related to basic accreditations and quality assurances, but the application process does not assess the qualifications of individual providers or physician safety records.

Chubb’s did all that in an application package that rivaled the length of War and Peace. But her facility would be a birth center — not a hospital — and those certificate of need applications had an additional, unique requirement: a transfer agreement. Several states, including Georgia, require birth centers to secure an agreement with a local hospital stating that, in the event of an emergency, the hospital will admit its patients. Chubb couldn’t get any of Augusta’s three hospitals — her direct competitors — to sign.

“The Department [of Community Health] has determined there is a general need for the proposed project,” the evaluation decision read. Projections outlining the number of women of reproductive age in the region showed there would be enough births to support the venture, and the letters of support submitted by community members demonstrated how much they craved a birth center. But without a transfer agreement, the department still denied the birth center’s application in its decision. The area hospitals had effectively blocked the facility.

Chubb sued the state, arguing that the transfer agreement requirement is redundant. Federal law already mandates that hospitals accept all patients in an emergency.

Birth centers care for low-risk pregnancies. About 2% of deliveries at birth centers nationwide require an emergency hospital transfer. Only 15 states require birth centers to secure certificate of need approval, and even fewer require a transfer agreement. More than 90% of all birth centers nationwide are in states that do not require such an agreement.

When Chubb applied, the package included 150 letters of support. That number has since risen to more than 500, as she continues to fight to open the center. There are letters from women desperate for a care option that doesn’t require being admitted into a hospital, Black women fearful that having a baby outside of a birth center could risk their lives.

“I am a 25-year-old, African American woman petrified at the thought of having a child in Augusta, let alone Georgia,” one letter reads. “The only way I would feel comfortable having a child in Augusta is when they decide to build a local birth center.”

Another supporter wrote, “Black women should be able to feel comfortable giving birth without questioning if the providers value their lives.”

But gaining the backing of local politicians was more difficult. Chubb’s meeting with then-Mayor Hardie Davis Jr. was canceled, and the letter of support that was promised never came through. Chubb felt as though much of her communication with Richmond County commissioners went unanswered. She worried that the hospitals had more political power than she had realized. Then, new revelations appeared.

Brandon Garrett, one of the county commissioners, is a board member for Piedmont Augusta, formerly known as University Hospital. Garrett said he communicated with Chubb via email, but because he didn’t understand the certificate of need process, he reached out to the hospital for more information.

“Reading between the lines, of course, they’re not going to help somebody else that can potentially take business away from them,” he told Capital B. Representatives of Piedmont Augusta could not be reached ahead of publication.

Commissioner Catherine Smith Mcknight replied to Capital B’s initial request for comment but did not respond to requests to schedule a call. The eight other commissioners did not respond to multiple requests.

Chubb has been on a mission to expand access to birth centers in Georgia, a state where there are only three, all more than a two-hour drive from Augusta. She fought with the hospitals when the application was denied, she said, and ultimately sued the Georgia Department of Community Health’s commissioner, the interim executive director of the Office of Health Planning, and the chairman of the board of Community Health.

After Chubb filed her lawsuit, a federal district judge dismissed the case in late February, after each defendant filed motions to dismiss the complaint. She says she will appeal the ruling.

“All of the hospitals around here decided we were going to be a threat to them,” Chubb said. “Money is more important than the women.”

Cuthbert, Georgia, is a small town of 3,000 people tucked in the state’s southwest region. About 85% of its residents are Black. With no hospital or obstetric care, Cuthbert is located in a maternal health desert.

(Photos by Eric Rich)

Blocking the competition

How certificate of need policies are enforced, and which facilities are required to submit proposals, varies by state.

New York was the first to institute a certificate of need program in 1964. More than two dozen other states followed suit, implementing similar laws over the next 10 years. In the 1970s, the federal government began requiring states to enact the certificate-of-need laws, withholding funds from those that did not participate.

At the time, policymakers believed the programs would help make sure there was an adequate supply of health resources, particularly in rural communities. They were intended to improve the quality of care, control costs, and encourage the expansion of hospital alternatives, like ambulatory surgery centers. Reducing the cost of services for both patients and providers was the goal. With limited competition, health care facilities might be able to thrive in rural communities, policymakers thought.

But as evidence mounted that the laws were not controlling costs and improving outcomes, but instead, undermining the quality of care, the federal government revoked the mandate in 1986, and many states dropped their programs. A few years after the repeal, then-U.S. Rep. Roy Rowland, a Democrat and physician representing rural areas of Georgia, said the program ignored the needs of his community. He urged his colleagues to dissolve the laws.

“It’s now time to abolish it throughout the nation,” he said.

Still, in the late representative’s state, the law persists.

Research shows that certificate of need laws have negative effects on rural communities and communities of color. States with certificate of need programs have fewer rural hospitals, and the regulation is associated with longer travel distances to care. In 2021, research by the Mercatus Center at George Mason University found that repealing the laws would increase the number of hospitals in Georgia from 176 to 250, including a jump in the number of rural hospitals. Reforming the laws has also eliminated Black-white health access disparities. One study shows that, in New Jersey, expanding hospitals’ capacity to perform heart procedures through certificate of need reform reduced long-standing disparities in access. When access increased, so did the number of Black patients served.

But the laws have widespread support from hospitals because “they limit their competition,” said Matthew Mitchell, an adjunct professor of economics at George Mason.

The Georgia Hospital Association, a nonprofit trade group that represents 145 hospitals in the state, did not respond to requests for comment.

Hospital executives earn $90,000 more in certificate of need states, he said, and facility profits tend to fall in the few years following the law’s repeal. A 2017 research paper by the Mercatus Center, a free-market think tank, found that donations and political action committee contributions affect application approval. In Georgia, a 1% increase in contributions by an applicant firm increased the odds of approval by nearly 7%, the largest increase of all three states included in the study.

Hospitals’ political power creates a system that benefits their financial incentives over Georgians’ needs for care. For Black folks, the bleak effects of those decisions show up in intensifying racial disparities across myriad health outcomes. Maternal health is one gap among many.

“Most women are cluelessly excited to have a baby, and we don’t know things are lurking around the corner waiting to rob us of that joyous experience,” said Krystal Reese, a full spectrum doula in Jonesboro, Georgia.

“We’re not adding more hospitals and birth centers. We are removing them. We’re limiting access,” she said. “How can things get better with fewer care providers?”

The landscape of certificate of need laws across the country is shifting as legislators in different states reconsider how the policy should play out in their health care system. During the COVID-19 public health emergency, many governors suspended their state’s certificate of need requirements in order to meet the needs of their communities. The laws don’t allow for the rapid health infrastructure adjustments that were necessary to address the coronavirus outbreak.

Conservative lawmakers have championed certificate of need reform and elimination for decades as a means to achieve a more free-market economy where service providers are able to open up with few regulations and compete among one another. More liberal advocates say the current system of certificate of need is failing to adequately gauge the health needs of Georgia’s diverse communities.

In February, a Georgia Senate committee approved a bill by a single vote that would replace the certificate of need system with a less restrictive “special health-care service” license, getting rid of some of the current requirements across most health specialties. The original version of the legislation, Senate Bill 162, called for complete certificate of need repeal.

Another bill targeting the system, Senate Bill 99, was approved in the state Senate last month by a vote of 42-13. It aims to remove certificate of need requirements for hospitals in rural counties. It now heads to the House of Representatives.

In 2019, Georgia lawmakers passed legislation waiving the fee rural hospitals must pay when applying for certificate of need approval, but even so, hospitals are not seeking to expand to rural areas because of the low patient volume and high poverty rates.

“If a hospital can block a birth center from opening in Augusta, Georgia, then we should also be able to stop a hospital from closing and leaving a void in the community,” said Breana Lipscomb, senior advisor of maternal health and rights at the Center for Reproductive Rights. “If we are really talking about a certificate of need, that goes both ways.”

Vincent Gadson, a resident of Cuthbert, Georgia, says he is afraid of what having no emergency care nearby means for his community.

(Eric Cash)

‘We need a hospital’

Southwest Georgia Regional Medical Center shut down in Cuthbert as the pandemic’s national death toll approached 223,000. The morning of Oct. 22, 2020, dozens of community members gathered outdoors on its lawn. Shocked, they prayed. They grasped for a hint of security, asking for God to protect them.

For 70 years, the hospital brought a sense of safety to Cuthbert. Since its doors shut, patients have been flown to out-of-town hospitals for emergencies. Some to Macon, Georgia. Others to Atlanta or Columbus, Georgia. Tallahassee, Florida. Alabama.

You don’t miss your water until your well runs dry, said Kuanita Murphy, a Cuthbert native who leads Randolph County Family Connection Inc., a nonprofit that aids access to health and wellness services. It’s such a small town, she said, that residents’ needs are brushed under the rug.

Cuthbert resident Vincent Gadson, 61, has diabetes and suffered a stroke not long ago. Since then, he has focused more on eating whole foods with fewer chemicals and building an exercise routine. He enjoys hours-long bike rides and is more in tune with his mental health. But despite that effort, he is afraid of what having no emergency care nearby could mean.

“We need a hospital,” he said of his community.

Before the hospital’s closure, and before the coronavirus crisis, administrators had tried to secure $10 million in funding for critical upgrades and renovations. But once COVID-19 hit, “it simply pushed our hospital past the point of no return,” hospital CEO Kim Gilman told local news media at the time. Fifty employees lost their jobs at the hospital, although the medical system that owned the facility said it would try to place them in nearby facilities.

The pandemic thrust many American hospitals and health systems deep into financial difficulties. Some face bankruptcy, and analysis shows that about 30% of rural hospitals across the country are at risk of closing unless their finances improve. That is more than 600 facilities. Others have already closed, citing low insurance reimbursement rates, staffing shortages, and low patient volumes. As the cost of drugs, medical supplies, and equipment skyrocket, hospitals have found themselves facing historic challenges.

In Georgia, experts have pointed to the state’s decision not to expand Medicaid under the Affordable Care Act as a reason its hospitals and maternal care units are shutting down at a rapid pace. Still, provider reimbursement rates within Medicaid remain low, meaning extending that coverage may not be enough to keep facilities from shutting down.

When Cuthbert’s hospital closed, the community was stunned.

“It was a shock to a lot of us,” said Murphy. If they had known how close the hospital was to closing, residents said they would’ve done more to try to save it.

Randolph County ranks among the bottom in most health measures, including life expectancy, compared with other counties statewide. Those trends mirror its maternal and child health statistics, which experts say can be used as indicators of a community’s overall health. The lack of access to comprehensive health services explains, at least in part, why Randolph’s health outcomes are so dismal. Residents in its ZIP code, 39840, are over 40 miles from an obstetrician.

“We don’t have to be a victim in this series of hospital closures,” said Lipscomb with the Center for Reproductive Rights. “The state can be more proactive in keeping hospital doors open.”

‘Blood on their hands’

Childbirth is a complex process. Its outcomes are affected by many factors, including good medical insurance and quality prenatal care, which makes identifying who’s accountable for maternal deaths and complications challenging.

But expanding access to care is one way to improve Georgia’s bleak outcomes, experts say, and accountability for doing so lies with state regulators and lawmakers who hold the power to implement policies that encourage increasing services.

Georgia has some of the most restrictive laws in the country around midwifery care, advocates say, which further limits birthing alternatives, and health equity scholars say physicians tend to blame mothers for their health as opposed to examining the system within which they operate. For Black folks, racism infiltrates the system, further contributing to dismal racial disparities — from the systemic disinvestment in Black communities to individual providers’ racial biases.

The health that moms bring into pregnancy also influences labor and delivery, and the stress Black folks are forced to navigate when confronted with insults and discrimination over the course of their lifetime is linked to poor birth outcomes. It’s an effect experts refer to as “weathering,” where repeated exposure to racism breaks down a Black mother’s body prematurely.

Rural Black Georgians have found few successes in the fight against a system that, for generations, has caused mothers and their infants to suffer higher rates of negative outcomes. Instead, hospitals’ fierce lobby and strong political influence allows pockets of Georgia to be left with little to no maternal health care in one of the most dangerous states to give birth.

“The system either has to be dismantled or rebuilt,” said Bishop, the doula. “So many groups of people have blood on their hands.”

Correction: A previous version of this story incorrectly named the organization for which Breana Lipscomb works. It is the Center for Reproductive Rights.