Cambodian refugees cope with war trauma by reinforcing culture and community

This story was originally published in KVPR with support from the 2022 California Fellowship.

Danny Kim walking in his backyard garden on Sept. 15 in Fresno, Calif.

Soreath Hok / KVPR

CHJ · Cambodian Refugees Cope With War Trauma By Reinforcing Culture And Community

This story is part of the series Health and Healing for Cambodian Survivors.

FRESNO, Calif. — It’s a hot day in Fresno and Danny Kim’s backyard feels like an oasis. A glistening pool looks inviting in the sun and two dragon statues made at the Cambodian Buddhist Temple guard the entrance to a peaceful pond garden. For Kim, this space is a piece of heaven that he’s built for himself and his family.

“I feel very proud because all my family is doing really well and I think part of it is because we didn't forget where we came from,” he says.

The 47-year-old has lived through a painful part of history in his native Cambodia. In the 1970s, the communist Khmer Rouge takeover led to a brutal regime that killed millions.

Kim was just an infant in 1975, the start of the Khmer Rouge’s four-year regime. He describes some of his first memories as a toddler.

“I was awakened by the sound of shootings and people screaming.” He says the sound was something he soon became used to as a child. “We don't know what war is because you grew up in the middle of it so you thought that was normal.”

Across from him, under a shaded patio sits his sister, 54-year-old Chinda Kim.

“I was the oldest of my siblings. They took me from my family because I was the biggest one, 7-years-old,” she says.

Chinda Kim recalls some of her most painful memories of that time.

“I kept coughing up blood. I tried to walk. I wasn't worth anything to them dead or alive, no benefit to them. If I wasn't able to keep working, they would have killed me,” she says.

She was put into forced labor with other children her age, digging and hauling dirt.

“I missed my parents, I didn't know what to do, I was afraid they would kill me so I just stayed,” she says.

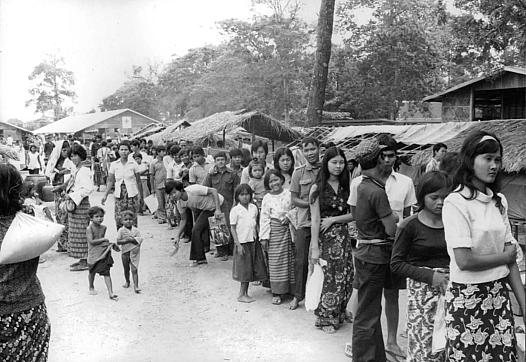

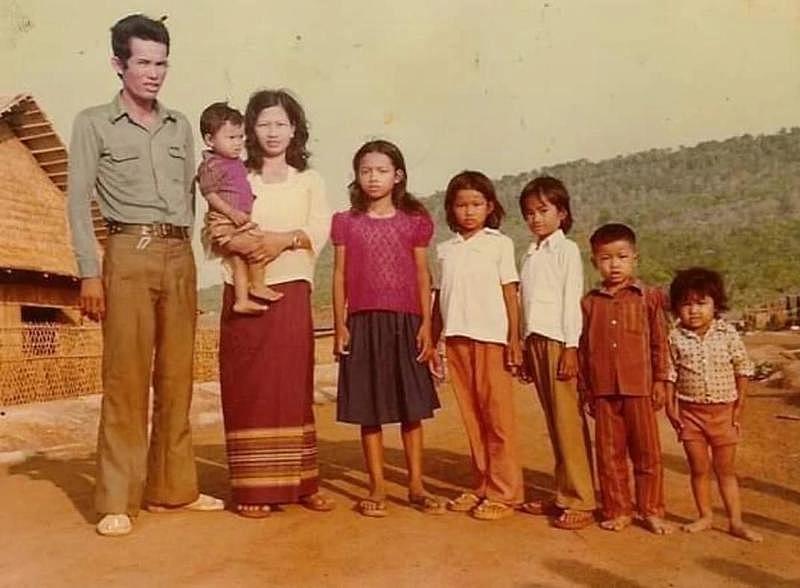

By 1979, when the regime fell, Chinda was reunited with her parents, Danny and two other siblings. The family set out toward the Thai border, hoping to find a refugee camp. Danny remembers walking non-stop for two days and two nights. “We started seeing bodies on the side of the road,” he recalls.

Chinda and Danny Kim are two of the tens of thousands of Cambodian refugees who fled to the United States after the genocide. Yet neither has ever sought therapy to cope with their trauma or received any other form of mental health treatment.

“We survive the death camps. We survive the starvation. We survive the war,” Danny Kim says.

Processing the Trauma of War and Genocide

A 2015 study in the journal Psychiatric Services examined how Cambodian refugees in the U.S. accessed mental health care. It found that language was a major challenge for them. The study showed 95 percent of Cambodian refugees who saw a psychiatrist needed to use an interpreter; as did nearly 80 percent of those who saw another type of mental health professional.

According to the American Psychiatric Association, trauma survivors are best treated through evidence-based therapy, the practice of applying research-based treatments tailored to a patient's individual needs and preferences.

But the lack of providers who speak Khmer is cited as one of the factors keeping more Cambodian refugees from receiving treatment.

At the Center for Empowering Refugees and Immigrants, that isn’t an issue. The non-profit in Oakland has many Cambodians on staff who speak fluent Khmer. Most of their clients seeking mental healthcare are Cambodian refugees.

Kate Wadsworth specializes in trauma therapy and is the center’s clinical director. She’s worked with Cambodian refugee clients here for over a decade.

“Can you imagine, for four years thinking you're going to die every single day and watching people die in front of you and being forced to work. Tell me, is that going to go away for you? You really think it's going to go away from you? No it doesn't go away,” she says.

At CERI, Wadsworth oversees a program that isn’t just focused on therapy. “Therapy is an important part of it, but I don't know if I'd say it's the primary part of it. I think the community part of it is the primary part of it,” she says.

It was this community that drew Wadsworth to continue working at CERI. “This population spoke to me because of the resiliency and the beauty of all the clients,” she says. “There's just this beautiful nature with all the clients that I work with, that I feel like in the healing that I help them do, I do my own healing because our relationship is so deep.”

Wadsworth says she can be her authentic self with her clients, which also encourages their openness and relationship-building. “Just the fact that I hug my clients - that my clients, participants, whatever words you want to use - we hug each other. We tell each other we love each other. I share things with them,” she says.

Part of the trauma is the feeling of being alone, which is why Wadsworth says just having someone who can listen can be an important part of healing. “Just to be able to share it and to be able to talk about it and not be alone and to say, 'Yes, many people feel this way.’ Many people feel a lot of shame that they had to walk by people who were getting hurt and they had no choice, you had no choice,’” she says.

Some longterm impacts that Wadsworth has observed with genocide trauma survivors include physical symptoms such as diabetes, high cholesterol, arthritis and chronic pain. These physical manifestations were just part of the problem, she says.

The treatment plans include group outings and other activities that help build a sense of community, she says.

“I think we realized pretty early on that individual therapy wasn't going to work, that we really needed groups, that we really needed activity-based stuff,” Wadsworth says

This is part two of KVPR’s five-part series, “Health and Healing for Cambodian Survivors.” In the next story, we learn more about how CERI is meeting the mental health needs of the community.