Purpose in the pain: Cambodian refugees pave a path forward, decades after resettlement

This story was originally published in KVPR with support from the 2022 California Fellowship.

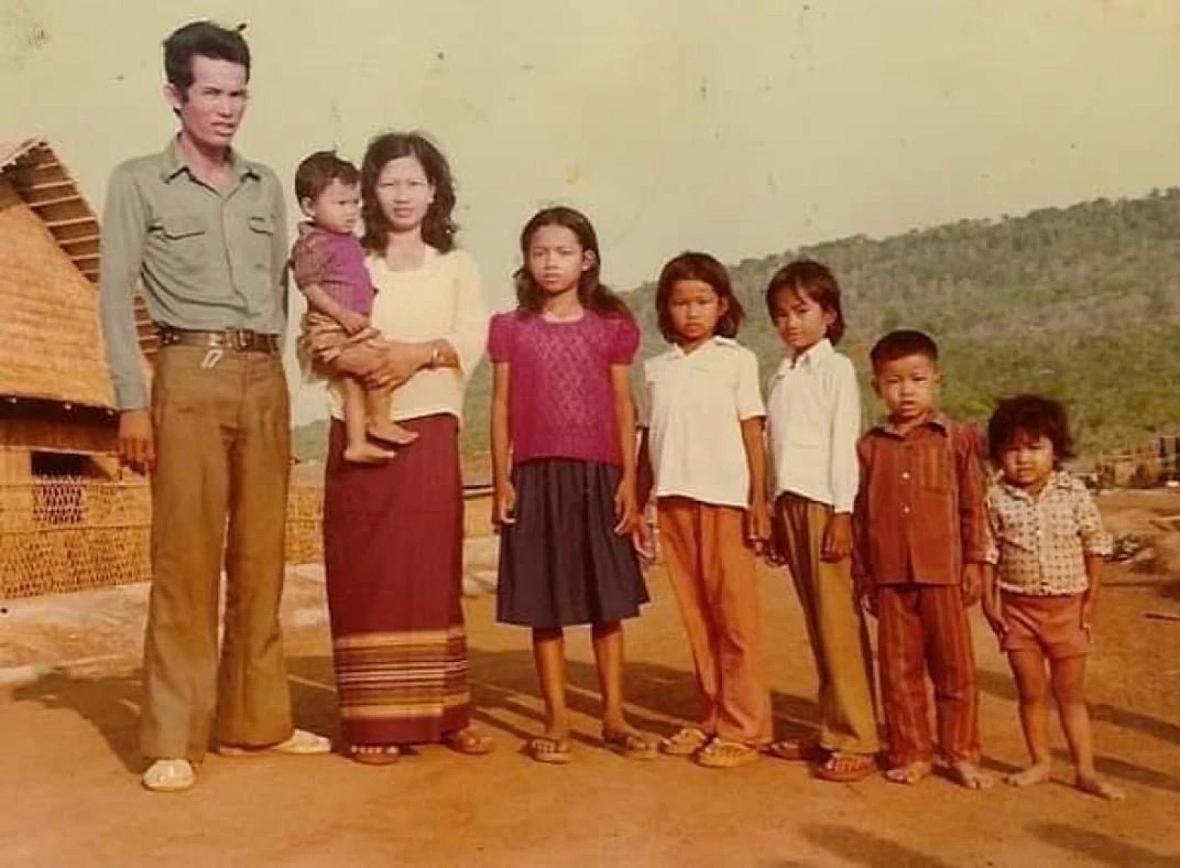

Danny Kim's family photo at a refugee camp in Thailand where they stayed after the fall of the Khmer Rouge regime in 1979.

KVPR

CHJ · Purpose In The Pain- Cambodian Refugees Pave A Path Forward, Decades After Resettlement

This story is part of the series Health and Healing for Cambodian Survivors.

FRESNO, Calif. — There was no such thing as a childhood for siblings Danny and Chinda Kim. What little of it Chinda had experienced suddenly ended on April 17th, 1975 - the day that Cambodia fell to the communist Khmer Rouge regime led by dictator Pol Pot.

“We didn't know what was going on, we just followed everyone. I was 7 years-old, holding my parents’ hands,” she says.

Like millions of other Cambodians, the soldiers told them they’d be gone for only a couple of weeks. But it was the beginning of a nightmare that lasted years.

“I lived far away from them for three years, eight months,” Chinda Kim recalls, breaking into tears. “They separate me from my parents.”

The Khmer Rouge evacuated everyone into the countryside. Immediately, artists, professionals and intellectuals were executed. Every person left was forced into slave labor - even children.

“They made us work digging. They just ordered us to do any kind of work, Pol Pot’s people,” Chinda Kim says.

On her way to work or to get in line for food, the young girl would see her siblings standing outside their hut.

“I would miss them and want to embrace them, but I was afraid. When they would send us to work, we had to walk by there and my siblings would recognize me and stand at the entrance calling out to me, but I wouldn’t dare,” she says.

Group leaders warned her to tell her siblings not to talk to her, to pretend like they didn’t know each other. It was this yearning to be with her family that led her to run away with another young girl.

“We missed our families, being away from our siblings and parents, so we ran during the night,” she says.

It didn’t take long before they were caught. They were hung up with ropes and beaten in front of the other kids - made as an example. Five decades later, she still has a scar on her back.

“I said to myself, I have to stay alive,” she says.

In fact, everyone in her family made it out alive. After the regime fell in 1979, the family made their way to a refugee camp in Thailand, then eventually to California. At home in Fresno today, Chinda Kim’s life still revolves around her family.

“These days my life is caretaking for my family,” she says.

Now 54, she’s a single parent with two adult daughters, and she also cares for a disabled sibling. When both her parents fell ill, she took on the responsibility full-time. Her dad, who suffered a stroke, needs 24/7 care. Being the caretaker came at a personal cost, she says.

“I never got a chance to go out and have my own career like my other younger siblings because it’s my fate to care for my mom and dad, my disabled sibling,” she says.

Her dedication made it possible for her younger brother, Danny Kim, to grow his career over 24 years with the Fresno Police Department.

Searching for a Sense of Order

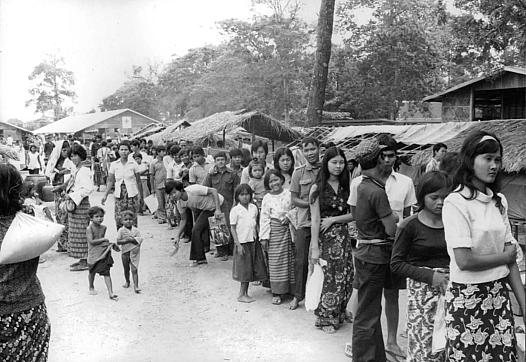

Most of Danny’s earliest memories started at the refugee camp in Thailand where his family fled after the fall of the Khmer Rouge.

They lived in tents at the camp for about five years before a church sponsored them to come to the U.S in 1985. After a few months in Texas, the family headed west to California. A relative who lived in Long Beach said it was better there, with lots of other Cambodians.

But for Kim, it was hard to fit into a foreign country starting at the age of 11. For him and many other young Cambodian refugees, the transition to American life was harsh. He didn’t feel welcomed.

“I’m getting jumped, I’m getting beat up, discriminated against. Sometimes I want to go back to the refugee camp,” he recalls.

To fight back, he sought a sense of order. “I just look at law and order as something that I feel I need because of my experience,” he says.

After graduating high school, a counselor suggested he go to law school. Kim studied to be a lawyer. But it was his experience working for the San Joaquin Delta community college police department that changed his path. “I received numerous awards for preventing crimes at school because I came up with creative ideas and committed my own time to do it,” he says.

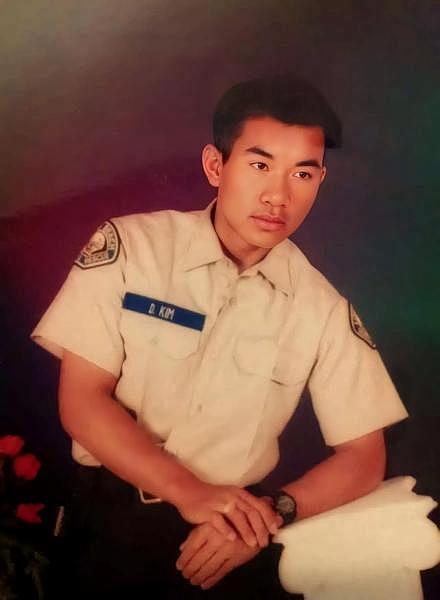

While visiting his sister Chinda in Fresno, Danny applied to work at the Fresno Police Department. He was accepted as a cadet in the police academy, graduated and joined the force in 1998.

Today, there’s one room in Kim’s home that documents some of the proudest moments in his career. “I have very little space in my house, so I utilize this one room,” he says surveying the front room of his home.

He calls it his “office”, which is more of a place to gather for impromptu karaoke sessions, or to jam on the many instruments placed against the walls.

But it’s the shiny plaques, framed certificates and police memorabilia decorating the walls that first draw my eye around the room.

“One of my most proud moments to be honest with you, it’s the life-saving medal,” he says pointing to a gold medal on the wall. “It’s the certificate of special congressional recognition.”

Danny Kim received the medal in 2012 after he jumped into a canal full of water to save four people trapped in a car.

Also on the wall is a recognition from the City of Fresno: a “Man of the Year” award in 2019 and a special proclamation for “Detective Danny Kim Day.”

And as one of only two Cambodians on the police force, Danny Kim is an integral part of Fresno’s Khmer community.

“They look up to you. They expect you to be the liaison of the community. The Cambodian people call me for everything,” he says.

As someone who also survived the Khmer Rouge, Danny Kim is an insider who remains deeply connected to the needs, concerns and nuances of people in his community, which can often clash with law enforcement due to lack of understanding. He has helped to bridge gaps in language and culture.

“Just remembering some of the stuff that I've seen and hearing stories from my sister or my parents, I think that's what inspired me to work hard and to achieve something. Because if I don't do it and if no one's doing it, you know, what we went through is like, meaningless,” he says.

The wall of framed certificates in his office is proof of that, Danny Kim says. “Just to show my children, and my family, the younger generation just to see that it's not impossible.”

_______

This is part four of KVPR’s five-part series, “Health and Healing for Cambodian Survivors.” In the next story, we learn more about how building community in Fresno is helping survivors of the Khmer Rouge genocide heal.