Can AI help mental health crisis? Nearly 100 students, parents and clinicians weigh in

The story was originally published by Cincinnati Enquirer with support from our 2024 National Fellowship.

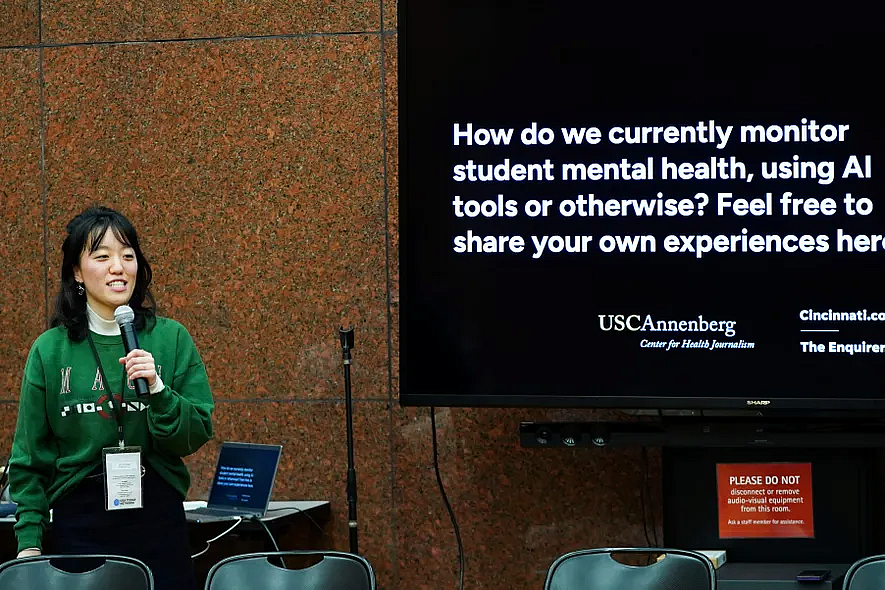

Enquirer health and environment enterprise reporter Betsy Kim hosts a community discussion about AI and mental health, Wednesday, Oct. 23, 2024, at the Cincinnati and Hamilton County Public Library main branch in Downtown Cincinnati.

Frank Bowen IV/The Enquirer

Enquirer health and environment enterprise reporter Betsy Kim speaks during a community discussion about AI and mental health, Wednesday, Oct. 23, 2024, at the Cincinnati Public Library main branch in Downtown Cincinnati.

Frank Bowen IV/The Enquirer

Guests listen as Enquirer health and environment enterprise reporter Betsy Kim speak during a community discussion about AI and mental health, Wednesday, Oct. 23, 2024, at the Cincinnati and Hamilton County Public Library main branch in Downtown Cincinnati.

Frank Bowen IV/The Enquirer

A woman speaks during a community discussion about AI and mental health, Wednesday, Oct. 23, 2024, at the Cincinnati Public Library main branch in Downtown Cincinnati.

Frank Bowen IV/The Enquirer

Enquirer real estate enterprise reporter Sydney Franklin speaks during a community discussion about AI and mental health, Wednesday, Oct. 23, 2024, at the Cincinnati Public Library main branch in Downtown Cincinnati.

Frank Bowen IV/The Enquirer

Teena Apeles, national engagement editor at the Center for Health Journalism at USC, speaks during a community discussion about AI and mental health, Wednesday, Oct. 23, 2024, at the Cincinnati Public Library main branch in Downtown Cincinnati.

Frank Bowen IV/The Enquirer

A woman raises her hand to pose a question during a community discussion about AI and mental health, Wednesday, Oct. 23, 2024, at the Cincinnati Public Library main branch in downtown Cincinnati.

Frank Bowen IV/The Enquirer

Enquirer health and environment enterprise reporter Betsy Kim speaks during a community discussion about AI and mental health, Wednesday, Oct. 23, 2024, at the Cincinnati and Hamilton County Public Library main branch in Downtown Cincinnati.

Frank Bowen IV/The Enquirer

Enquirer education reporter Madeline Mitchell speaks during a community discussion about AI and mental health, Wednesday, Oct. 23, 2024, at the Cincinnati Public Library main branch in Downtown Cincinnati.

Frank Bowen IV/The Enquirer

Teena Apeles, national engagement editor at the Center for Health Journalism at USC, right, speaks during a community discussion about AI and mental health, Wednesday, Oct. 23, 2024, at the Cincinnati Public Library main branch in Downtown Cincinnati.

Frank Bowen IV/The Enquirer

A woman speaks during a community discussion about AI and mental health, Wednesday, Oct. 23, 2024, at the Cincinnati Public Library main branch in Downtown Cincinnati.

Frank Bowen IV/The Enquirer

A man speaks during a community discussion about AI and mental health, Wednesday, Oct. 23, 2024, at the Cincinnati Public Library main branch in Downtown Cincinnati.

Frank Bowen IV/The Enquirer

Enquirer health and environment enterprise reporter Betsy Kim speaks during a community discussion about AI and mental health, Wednesday, Oct. 23, 2024, at the Cincinnati Public Library main branch in Downtown Cincinnati.

Frank Bowen IV/The Enquirer

A man speaks during a community discussion about AI and mental health, Wednesday, Oct. 23, 2024, at the Cincinnati and Hamilton County Public Library main branch in Downtown Cincinnati.

Frank Bowen IV/The Enquirer

A man speaks during a community discussion about AI and mental health, Wednesday, Oct. 23, 2024, at the Cincinnati and Hamilton County Public Library main branch in Downtown Cincinnati.

Frank Bowen IV/The Enquirer

Enquirer health and environment enterprise reporter Betsy Kim speaks with a guest at the end of a community discussion about AI and mental health, Wednesday, Oct. 23, 2024, at the Cincinnati Public Library main branch in Downtown Cincinnati.

Frank Bowen IV/The Enquirer

As part of our yearlong reporting project on how schools are using artificial intelligence to identify students with mental health issues, The Enquirer heard from nearly 100 people in the Cincinnati community.

Here's more on who they are and how they felt.

Most were students, parents, mental health clinicians and youth workers. Close to 80 people filled out our survey, while around 20 attended our library listening session, which was open to the public, to share their thoughts.

Cincinnatians expressed everything from cautious optimism to uncertainty and worry about having AI used to help determine whether someone is suicidal, depressed, anxious. Many said their biggest concerns about using AI this way were protecting students from privacy violations and biased results.

“My concern would be that once AI said a student was a danger, they would be treated as such,” shared one school administrator. “But, I also see the helpful aspect of it bringing up someone who may have slipped through the cracks.”

Over half think AI can help youth mental health crisis

People who thought AI would help solve the youth mental health crisis eked out a narrow majority – 54% – over people who disagreed or were not sure. This larger group agreed or strongly agreed that an AI-powered app that detects signs of distress could help address the youth mental health crisis.

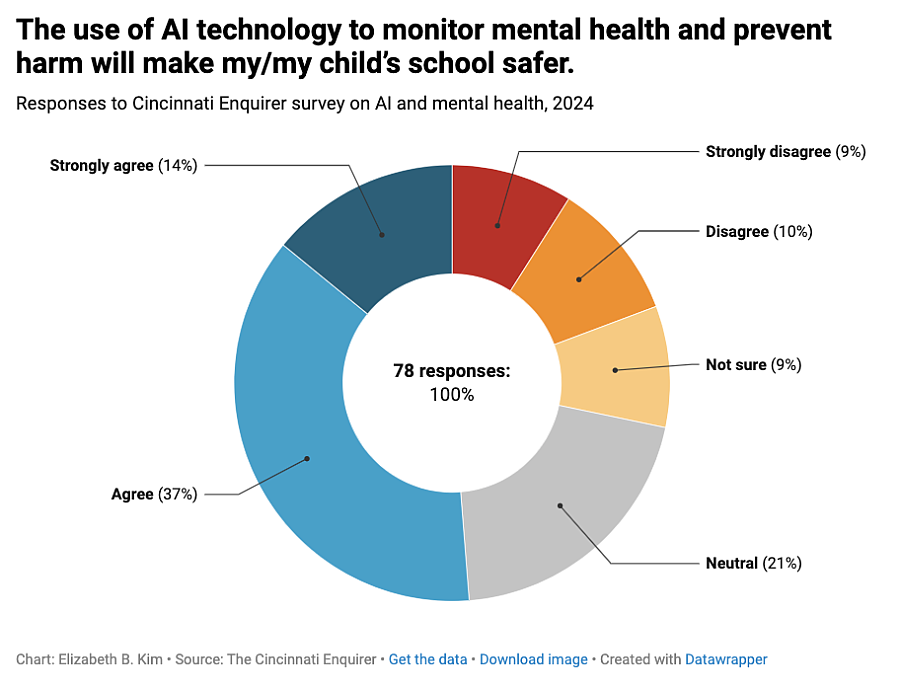

51% said that AI would make schools safer.

And some clinicians who attended our listening session saw value in using AI to predict suicide attempts.

“We’re really, really, really bad at predicting human behavior,” said Paul Crosby, a psychiatrist and the president of the Lindner Center of Hope, a mental health center in Mason. “I understand why solutions like this are being sought because we haven’t come up with good ones ourselves.”

Isaac Trice, a clinical counselor at Talbert House in Western Hills, said that algorithms are already playing a role in mental health diagnosis for his clients.

“Clients come in and say, well, TikTok told me that I’m a narcissist,” he said. “So I do think that it's important for us to be on the cutting edge and to use these tools.”

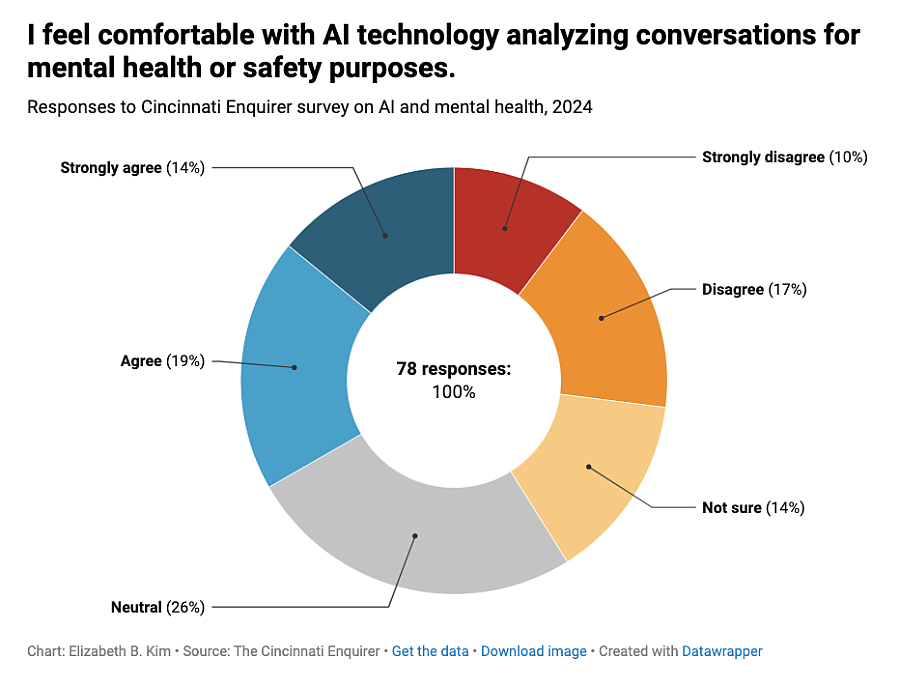

Still, every AI-related question on the survey resulted in 30% or more of respondents responding with “neutral” or “not sure”, indicating a clear uncertainty among many about using AI to help detect mental health issues.

Gharrie Hoffman, who has a master's degree in community counseling, doesn’t love the idea of using AI but felt she doesn’t “know enough about it.” She wants to see results proving it works before making a judgment call.

1 in 3 feel comfortable with AI recording therapy sessions, most people concerned about bias

The question that created the most even split among respondents asked whether respondents were OK with AI listening to their therapy sessions: 33% of respondents said they felt comfortable with it, while 27% said they didn’t.

Owen Kovacic, an undergraduate at the University of Cincinnati, described having AI listen to therapy sessions as “intrusive and terrible for trust.”

Recent Oak Hills High grad Quinn Merriss is worried that using AI to detect mental health issues could lead to kids being involuntarily hospitalized in cases where it's not necessary.

Merriss also wondered whether therapists using AI would discourage students from seeking help. “How many kids are gonna stop talking, period, because they don’t want it involved?” they asked.

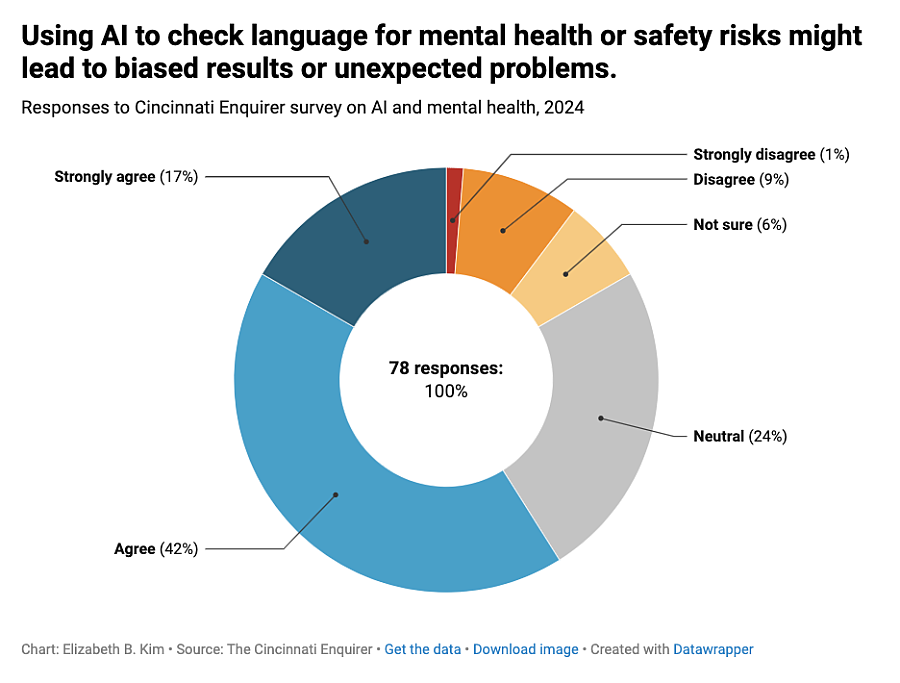

The question that produced the clearest majority asked about bias. Nearly 60% of respondents said that using AI to check language for mental health or safety risks might lead to biased results or unexpected issues, while 10% said it wouldn’t.

“When it comes to AI it can be made biased due to the information it is fed,” said Awa Bolling, an undergraduate at UC, a sentiment echoed by at least two other students.

Some people expressed doubts about using technology like AI to try to solve a mental health crisis that may have been caused by an excess of screen time in the first place.

Trice, the clinical counselor at Talbert House, put it this way: “When it comes to AI, are we chasing one pill with another?”

People agree we need more clinicians, disagree on how to make schools safer

Students from high school to graduate school expressed widespread agreement on the need for more accessible mental health services.

Increasing the availability of mental health clinicians, decreasing the cost of therapy, and giving students more time during the day to dedicate to their mental health, they said, were ways to get more students help. Awa Bolling, the undergraduate at UC, said that “more leeway with academic success” could take pressure off of stressed students.

Respondents agreed that schools could be safer but differed in their opinions about what that should look like.

A handful of people suggested increasing the number of police officers on campus. Still others felt that security equipment such as door locks and metal detectors were important.

More than one person identified hallways as areas that need to be monitored for bullying. According to one student from Taft High School, having adults in hallways “protecting students from bullies” and “escorting the victim to class” would make a difference.

As the director of the Trauma Recovery Center at The Neighborhood House, Sheila Nared helps youth victims of violent crime process their trauma and practice resilience.

Nared believes that giving communities most affected by violence a say in decision making is key to preventing violence in the first place.

“Those closest to the problem are those closest to the solution,” said Nared, but also “farthest from the resources and the power.”

What gives people hope? Hope Squad helps

Listening session attendees cited young people talking about their mental health as a sign that the stigma is decreasing, as well as increased access to mental health clinicians.

Carlie Yersky, a clinical counselor for Greater Cincinnati Behavioral Health, said she draws hope from the access that students have to trained mental health clinicians within their schools.

“When I was a kid, we did not have therapists in school,” said Yersky. “Now every school in Cincinnati is partnering with some mental health agency.”

Other attendees emphasized the importance of human and community-centered solutions to the mental health crisis.

“Create a culture of people caring about other people,” suggested Olive Weaver, a senior at Mason High, “rather than delegating any of the work to AI.”

Weaver and other listening session attendees pointed to Hope Squad, a peer-to-peer suicide prevention program implemented in hundreds of schools around Ohio, as one example.

At Mason High School, Hope Squad is a class with an enrollment of over 80 students. Each grade has their own Hope Squad team, led by a teacher adviser, which meets four days a week. Hope Squad members are charged with keeping an eye out for peers who are struggling and connecting them to a teacher or counselor if they need help.

Hope Squad members at Mason High School meet four times a week to check in on each other and classmates as a part of a peer-to-peer suicide prevention program.

Provided By Tracey Carson

“Often our kids see the issues well before the adults do,” said Beth Celenza, one of the school’s four Hope Squad advisers, so the class is about “empowering the students to be able to do something with that information.”

Prior to the implementation of Hope Squad in 2017, the school district averaged one suicide per year, said district spokesperson Tracey Carson.

It’s just one of the interventions the district established since then, said Carson, but together, the interventions seem to be working.

“I haven’t had a suicide since.”

How we did this

The Enquirer spent the past year reporting on how schools are using artificial intelligence to identify students with mental health issues. As part of our project, we took a two-pronged approach to hearing from the community.

First we released a survey that we distributed online and in person, in areas with high foot traffic such as The University of Cincinnati, Findlay Market, and The Neighborhood House, a social services organization in the West End. Next, we hosted a listening session at the Cincinnati and Hamilton County Public Library main branch downtown, open to anyone.

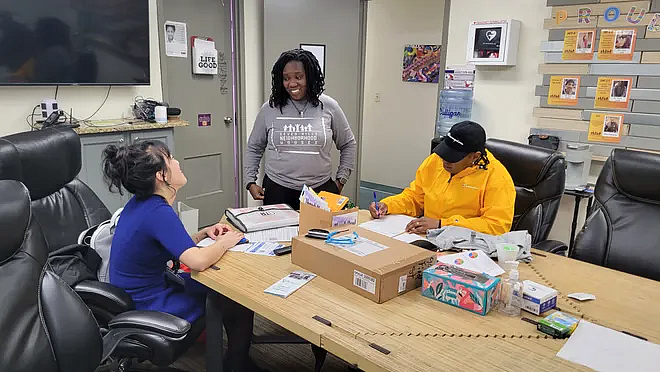

Enquirer health reporter Betsy Kim chats with Terana Boyd and Deseree Boyd as they fill out surveys. Both work with youth at The Neighborhood House in the West End.

Provided By Teena Apeles

The result was that we heard from a large and diverse group of Cincinnatians who ranged from teens to those over 60 years old.

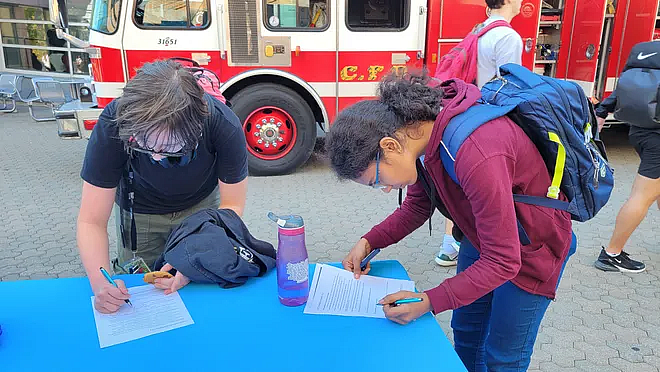

University of Cincinnati students fill out The Enquirer's survey on AI and mental health.

Provided By Teena Apeles

The breakdown of survey respondents consisted of 64% students, and 23% were parents. Another 9% were mental health providers and 7% worked with kids in schools or community organizations. Most parent respondents had high school-aged kids or younger and lived in areas that stretched from Fort Mitchell, Kentucky, to Cincinnati suburbs like West Chester Township.

The racial breakdown: 37% of respondents were Black, 37% were white, and 23% were Asian. Other respondents were Hispanic or Latino, Middle Eastern, North African or mixed race.

If you or someone you know is thinking about suicide, help is available 24/7. Call or text 988 or chat at988lifeline.org.