We know that cost cutting on mental health care is ineffective and expensive — we keep doing it anyway

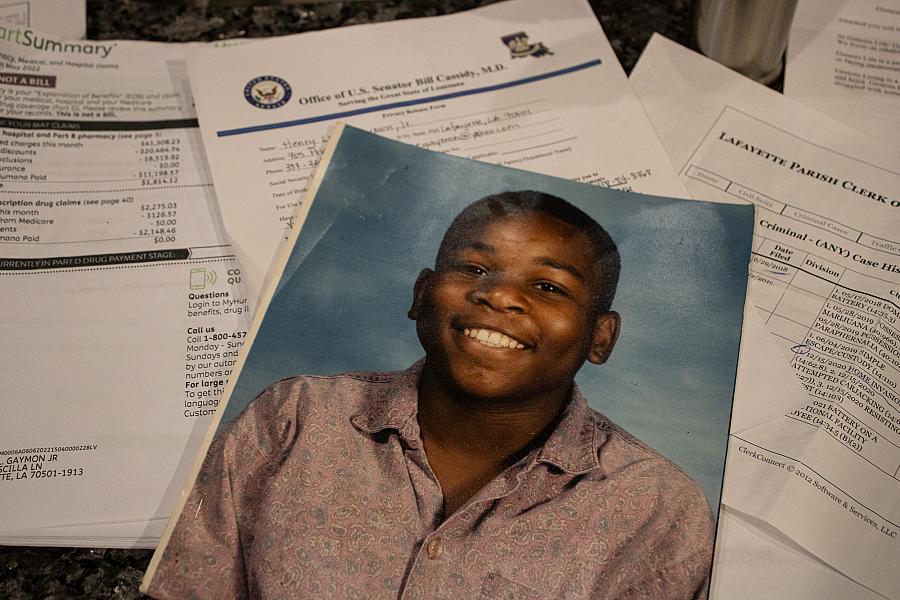

Henry Gaymon, one of the subjects of the author’s series, is unable to live on his own and continues to cycle through short-term hospitalization, incarceration and short-term living arrangements.

Alena Maschke

Driving across the campus of the former Central Louisiana State Hospital in Pineville on a reporting trip for my story on the effects of deinstitutionalization, I couldn’t help but imagine the possibilities.

There’s the baseball diamond, where staff and patients once played together, the bleachers covered in weeds and vines. A little further down a winding path, across a small creek and hidden behind overgrown shrubbery, stands the greenhouse where patients once tended to plants as a form of occupational therapy. Farther toward the edge of the 300-acre property sits the old dairy, perched upon a hill overlooking Lake Buhlow, where patients once cared for cattle that produced the milk and cheese they ate and sold for the benefit of the state.

This idyllic picture of the since abandoned state asylum isn’t meant to romanticize the past.

Researchers asked to produce a report on behalf of a company interested in redeveloping parts of the former state hospital grounds found that patients — often referred to as “inmates” — lived in facilities that were “of poor quality and overcrowded.” Further, they found that “the hospital was understaffed and lacked medical professionals, and while patient labor was often used as a means of occupational therapy, it also exploited the patients as a means of cheap labor for the benefit of the hospital.”

Human rights abuses, poor health outcomes and a lack of progress in healing the conditions that led patients to be institutionalized in the first place were at the core of the deinstitutionalization movement that took hold in the U.S. starting in the 1950s. Warehousing people with severe mental illness indefinitely was thought to be inhumane — and it is. So is leaving them to languish on the streets and in correctional facilities.

Like many state-run mental health facilities of that era, Central was forcibly emptied out. Its historic location finally closed in 2024, housing only a small fraction of the patient census that once occupied its ground of tree-dotted rolling hills.

But the idealism of the deinstitutionalization era presumed a willingness to invest in other methods of care, and that wasn’t grounded in reality. While state asylums across the country closed, the community health care centers meant to replace them never materialized.

In Louisiana, cost-cutting measures in the late aughts and early 2010s led to a slew of closures of state-run mental health facilities. Meanwhile, the state’s jails and prisons continued to fill up.

In 2012, the year Gov. Bobby Jindal closed one of the last state-run hospitals in Louisiana, a Times-Picayune report found Louisiana to be the incarceration capital of the world — incarcerating more people per capita than any other state, three times as many as Iran at the time and 10 times as many as Germany.

At the time, reporters found that financial incentives, along with notoriously harsh sentencing laws and practices, were at fault for the state’s packed jails. Today, local sheriffs say mental health and substance use are contributing to overcrowded jails, forcing corrections officers to act as mental health professionals, and forcing those with mental illness into facilities that aren’t meant for healing the conditions that landed them there in the first place.

This is where my reporting, which led me to a deep dive into the history of institutions housing mentally ill people, started.

Across the country, correctional facilities now serve as the largest providers of mental health care — with devastating results. A recent New Yorker expose detailed the deaths of mentally ill inmates by starvation and dehydration, making starkly visible the unsuitable environment those institutions and the system they are a part of present for those in need of mental health care.

Shortly after its opening, in 1906, the superintendent of Central Louisiana State Hospital, Dr. J.N. Thomas, appealed to the Louisiana legislature to appropriately fund the hospital. “The persons in these asylums are insane, it is true, but they are human beings after all,” Thomas said. “They have nobody to fight for them.”

In over a century since, those pleas ring as true as ever.

Caught in a cycle of incarceration, hospitalization and homelessness, many people with mental illness today continue to struggle as a result of the lack of public investment in their care. People like Henry Gaymon, one of the subjects of the series of stories I reported as a National Fellow at the Center for Health Journalism.

Henry Gaymon in a photo from his childhood.

Alena Maschke

Unable to live on his own and faced with a lack of access to long-term care, Gaymon continues to cycle through short-term hospitalization, incarceration and short-term living arrangements. It has made him vulnerable to neglect, abuse and further deterioration of his mental health and substance use issues. On his stations along the way, he has received care that is costly to taxpayers, but does little to help him lead a stable or comfortable life.

The same circumstances that made Gaymon a fitting subject for this story also made it difficult to report out his experience. He suffers from severe mental illness, the symptoms of which are likely exacerbated by years of self-medicating substance use, according to mental health professionals who have worked with him while incarcerated.

Interviewing him was a challenge and provided little insight into the facts of his experiences with mental health or correctional institutions. Few of the quotes from my conversation with him made it into the final story, but I still couldn’t have done it without him. Experiencing first-hand the challenges he faces in grappling with everyday life and witnessing the emotions he went through while describing his experiences provided insights that couldn’t be measured in a word count.

And like those patients Dr. Thomas told legislators about nearly 120 years ago, Gaymon has few people who are able to effectively advocate on his behalf. His mother is his fiercest advocate, herself writing to legislators on her son’s behalf, pleading with them to offer her son pathways to healing.

But as a woman in her 70s, Joyce Gaymon faces her own limitations in her ability to care and fight for her struggling son. After suffering a stroke, her memory of his stays in mental health and correctional facilities are hazy.

This is where documentation such as his criminal record and billing records from his health insurance provider helped fill in the fuller picture. And while comprehensive records of public spending on mental health care in Louisiana were lacking, they helped provide a snapshot of the public cost of caring for people with mental illness under our current system.

When the story published, Ms. Gaymon expressed her deep gratitude to us, despite the emotional toll the reporting process — several visits to her house, repeated requests for documents that were difficult to find — must have taken on her. Speaking with her and Henry allowed her an opportunity to be a public voice for him and others in his situation who are too often ignored, pushed into obscurity by a complicated web of judicial and medical institutions and left to their own devices.

Her feedback served as a reminder how important it is to fight through the frustrations of the reporting process and stay with the story, even if it becomes difficult to report. And it also made clear that the cost-cutting efforts focused on mental health are an expensive strategy.