Caught in WA's youth mental health 'disaster,' a teen with nowhere to go

This story was originally published in The Seattle Times with support from the 2022 Data Fellowship.

Jack Hays, seen in his bed at Mary Bridge Children’s Hospital in Tacoma in May, has stayed in the hospital for more than a year – including more than 250 days in a windowless room in the emergency department – as he waits for long-term care. He has autism, is nonverbal and has had violent outbursts, and he has been rejected from 60 facilities across the country.

(Erika Schultz / The Seattle Times)

Down the hall from where a tiny toddler is playing, past a colorful mural and a nursing station, 17-year-old Jack Hays lies alone in his hospital bed.

His head is shaved; he recently contracted lice. It’s May, and in the six months since he’s arrived at Mary Bridge Children’s Hospital in Tacoma, he’s gained almost 30 pounds. His room is empty but for a pair of socks discarded on the floor and two cat posters taped to the wall. A staff member is stationed outside his door around the clock, ready to step in when Jack hurts himself — or to call security when he becomes aggressive.

Jack doesn’t talk. But his mother, Greta Johnson, has an intuitive ability to understand what Jack needs. Sometimes they use sign language, but Greta often picks up on a slight movement or facial expression signaling Jack’s feelings.

On this day, his despair is palpable.

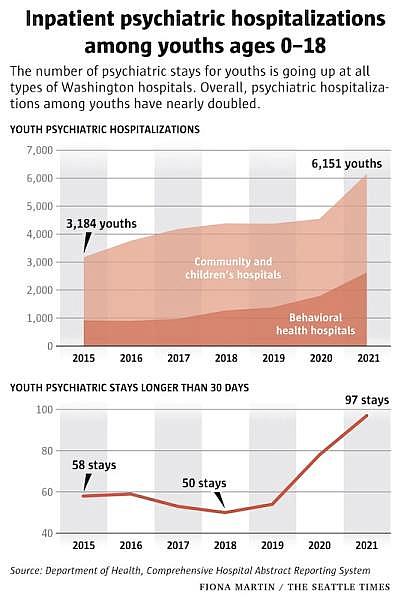

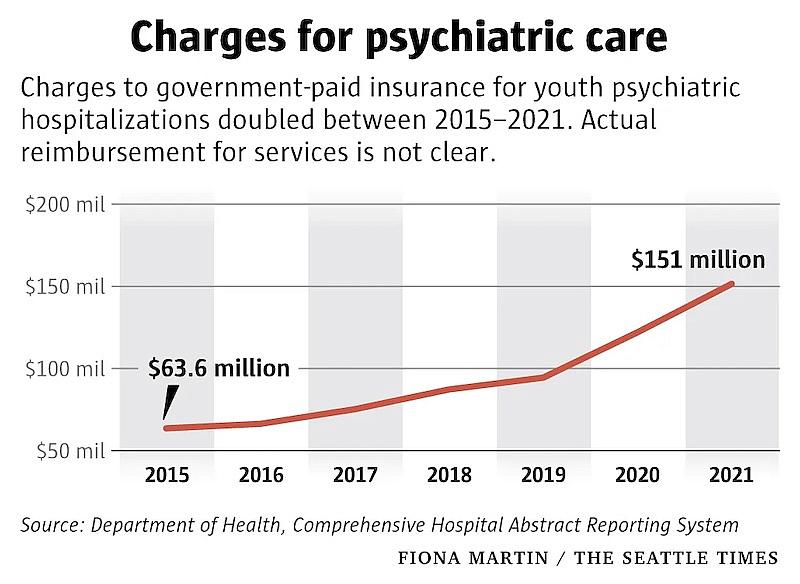

Jack’s situation is extreme but increasingly common. He’s one of a surging number of Washington children facing mental health challenges so severe that they require hospital stays. Between 2015 and 2021, the total number of hospitalizations nearly doubled among youth whose primary diagnosis is psychiatric, an investigation by The Seattle Times found. Charges to government insurance for youth psychiatric stays did double, rising to more than $151 million last year.

Times has spent the past year examining the toll of the youth mental health crisis at Washington state hospitals, interviewing families and medical staff, reviewing state budgeting documents and combing through tens of thousands of records that track youth psychiatric hospitalizations. This data analysis represents the first detailed accounting of the full costs of these kinds of hospitalizations in Washington during the pandemic: the physical and mental costs to the children who are stuck inside hospital rooms, and the financial costs to their families, hospitals and taxpayers.

The State officials have blamed pandemic-era school closures, social isolation and lack of access to mental health services.

But the inpatient data confirms what physicians have reported and national research supports. The youth mental health crisis in Washington crescendoed after COVID-19 arrived — but it didn’t appear overnight.

Elected leaders responsible for funding children’s mental health services didn’t prioritize these programs even as youth psychiatric hospitalizations were rising many years before the pandemic, a Seattle Times review of agency budget requests, governor’s office proposals and legislative funding decisions from 2017-2022 shows.

“It really is truly systemic, and it’s been increasing over time, and in fact, we’ve set ourselves up for it,” said Rep. Lisa Callan, D-Issaquah, co-chair of the Children and Youth Behavioral Health Work Group.

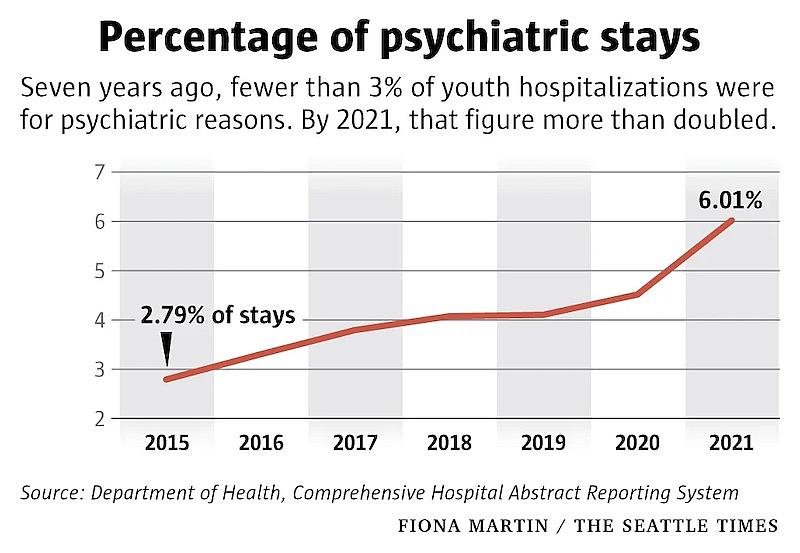

In general, youth hospitalizations for all conditions, including physical health, have declined over time. But psychiatric-related hospitalizations are surging. Seven years ago, fewer than 3% of youth hospitalizations were for psychiatric reasons. By 2021, that figure more than doubled.

All types of hospital settings, including community hospitals, children’s hospitals and free-standing psychiatric hospitals that serve youth, are reporting increases. Girls and youth assigned female at birth make up an increasingly large share — 71% of such hospitalizations last year. And while psychiatric units are equipped and staffed to treat youth with complex psychiatric symptoms, community and children’s hospitals like Mary Bridge usually are not.

Still, more youth keep coming.

And in the worst cases, like Jack’s, many aren’t leaving.

Longer stays

Jack and hundreds of other youth each year occupy a liminal space in the medical system that’s neither therapeutic nor medically necessary. He’s “boarding,” another word for warehousing psychiatric patients in hospital settings that aren’t suited to their needs.

Each year, hundreds of youth hospitalizations last for weeks if not months: Last year, at least 97 hospitalizations at Washington’s community and children’s hospitals lasted longer than a month — and of those, 13 were 100 days or longer. Long stays spiked during the pandemic.

Although long-term stays make up a small share of youth psychiatric hospitalizations overall, they are particularly trying on already overstretched hospital systems, especially as a triple threat of respiratory viruses — COVID, RSV and flu — sweeps the state. Boarders take up beds that would otherwise serve many children in a given day or month, said Tona McGuire, co-lead of the state Department of Health’s Behavioral Health Strike Team. Since April, an average of 20 youth were boarding every day at hospitals in Western Washington, according to a system hospitals use to share bed capacity information.

But youth like Jack are stuck in the hospital because they aren’t safe to discharge back home. And the intensive outpatient or residential care they need is overwhelmed with monthslong waiting lists. The pandemic created a “perfect storm” — a shutdown in services and a delay in getting youth treatment before they were in crisis — that resulted in a system swamped at all points, McGuire said. A mental health workforce shortage complicates solutions.

It’s a “disaster situation,” McGuire said.

“We started out with scarcity and then we have this massive patient surge,” she added. “When there is no place to send them, they’re sitting for days and weeks … that’s our equivalent of not enough ventilators to go around.”

Many of these youth are in emergency departments or in medical units without properly trained staff. And though boarders like Jack typically aren’t getting treatment, sleeping in the hospital can cost thousands of dollars each day.

Jack’s care has cost upward of $946,000 so far, or $2,483 per day, estimates from Mary Bridge suggest.

The hospital will eventually seek payment through Jack’s Medicaid plan; hospital officials said they expect to be reimbursed about $280 for every day of Jack’s stay. Mary Bridge will absorb any extra costs, hospital officials said.

Spending time in the hospital can also wreak physical and emotional havoc.

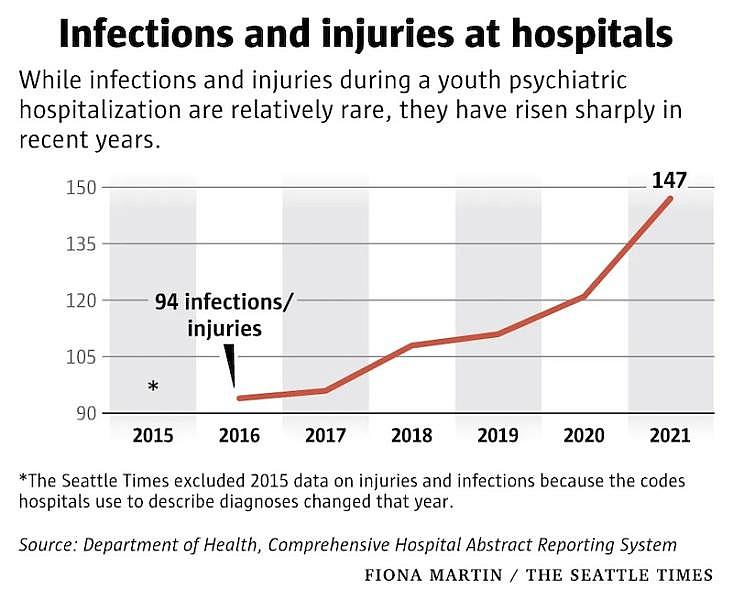

Since 2016, Washington hospitals have recorded at least 677 hospital-acquired injuries and infections during youth psychiatric hospitalizations. The inpatient records don’t offer details about how or why these conditions occur. But psychiatrists acknowledge youth sometimes self-harm while they’re hospitalized, or get injured during an outburst or when staff restrain them.

Jack has bitten nurses and regularly bites his own hands and wrists, Greta says.

She visits him every day, driving the half-mile from her home where she lives with her younger son, who, like Jack, is also nonverbal and autistic. Jack lived in a windowless ER room for five months, but by late April he’d been moved to a pediatric unit on the sixth floor. While the new unit still can’t provide the care he needs — it’s not staffed by a psychiatrist — he has a window and is allowed to take chaperoned walks.

Today, Jack heads toward a row of red Radio Flyer buggies intended for someone much smaller and curls his 6-foot frame inside. His mom pulls him over to a window that overlooks trees. “What do you see?” she asks. He’s silent, but leans toward the glass.

Back in his room, Greta tickles Jack, and for the first time today, he breaks into a deep laugh. Then Jack waves his hand, signaling he’s ready to be alone.

“I love you” she says, and kisses his face. He kisses back.

When the safest place isn’t safe

Jack, born on July 4, is Greta’s “firecracker.”

As a toddler, he started losing skills and his ability to talk, a worrying sign that Greta brought up to his pediatrician. By the time he was diagnosed with autism at age 4, it was too late for the earliest treatments. He was later diagnosed with a sensory processing disorder. And he’s been aggressive as long as Greta can remember.

Two years ago, Jack broke Greta’s rib. A year later, he bit, hit and kicked her in front of his therapist. When he has violent episodes, she said, “it’s like a light switch goes off and he’s a whole different person.” To keep herself safe while driving with Jack, she installed a caged barrier between the front and back seats of her car. She locks knives out of Jack’s reach. And she keeps pushing for behavioral health services that never materialize.

For years she pleaded with the state’s Developmental Disabilities Administration for help: “We are still in crisis, what are you doing for us?”

On Dec. 2, 2021, Jack gave Greta a concussion. He was brought to Mary Bridge, and, more than a year later, still hasn’t left.

“We’re exhausting every single option that could have ever existed because this is not an OK place for Jack to be,” said Vanessa Adams, a behavioral health social worker at Mary Bridge. Adams said she’s talked to admissions and sent Jack’s clinical notes to 60 different facilities across the country.

He was rejected by all of them.

Many facilities don’t accept autistic youth. Some were concerned about Jack’s aggression. Two initially accepted Jack, but later rejected him because of insurance complications and concerns about his age.

The hospital, Greta thought, would at least keep him safe.

On the sixth floor, Jack’s room is spacious. Greta says she’s thankful for several compassionate staff members.

But Jack has fallen into an even deeper depression, she said. The hospital isn’t set up for someone like Jack, who does well with routine and is sensitive to disruptions, like someone entering his room unannounced. A cocktail of antipsychotics, mood stabilizers and Valium, Greta added, has made him zombielike. He keeps gaining weight, too.

The longer youth are in the hospital, the more opportunity for their situation to worsen physically or emotionally, said Dr. Ravi Ramasamy, interim medical director at Seattle Children’s Psychiatry and Behavioral Medicine Unit. “You may learn new ways of getting your needs met, and they may be maladaptive,” he said.

Like overeating: Since 2016, at least 104 youth were logged as becoming morbidly obese because they consumed too many calories during psychiatric hospitalization, the state’s inpatient data shows. (Some psychiatric drugs are also tied to weight gain.)

Or maintaining cleanliness: 437 youth — mostly female — contracted urinary tract infections while hospitalized. UTIs are common at hospitals. But one sign of a person’s mental illness getting worse is when they stop taking care of themselves, Ramasamy said, and UTIs are highly correlated to hygiene.

Or self-harming or making attempts to kill themselves.

Hospitals recorded at least 37 cases of asphyxiation that happened while youth were hospitalized from 2016-2021, a vast majority of which occurred inside community or children’s hospitals, not psychiatric ones. Hospitals also reported at least 21 cases of youth fracturing bones. That number may be an underestimate, though: at least 39 additional fractures were marked as “not present on admission” during that period.

The data doesn’t make clear whether an injury is related to self-harm. But harmful behaviors are often why youth are hospitalized in the first place, Ramasamy pointed out.

“If the question is, do kids self-harm on the unit? Yes, obviously,” he said, referring to the PBMU.

Physicians, he said, have to weigh the risks of self-harm versus physically restraining youth to stop them. Restraints can cause trauma and are tied to bone and joint injuries, heart problems and, in rare cases, death. Because of this, restraint is typically the last resort: Staff usually first try to coach youth to stop hurting themselves or hold their hands to stop harmful behavior, said Lauren Huxtable, director of the behavioral support program at Seattle Children’s.

How often youth are restrained, however, isn’t clear. Data on restraint at Washington children’s hospitals is either incomplete or combined with adult records in a federal database that logs these practices.

Greta says she struggled to get information this fall when new bruises appeared and she suspected Jack was being restrained; the hospital eventually agreed to notify Greta more quickly whenever Jack was restrained. The hospital said Jack was restrained three to five times during his hospitalization with straps to hold down his limbs.

“His arms, they have these giant scratches up and down them like somebody grabbed him. But hospital staff keep saying it’s him self-injuring,” she said. “There’s just so much I don’t know because Jack can’t tell me.”

July 4 came and went — Jack turned 18 — and a spark of hope that he’d suddenly have more suitable options by aging into the adult mental health system quickly faded.

He was not doing well. His outbursts became more frequent, and sometimes, security couldn’t get to his room fast enough.

In early September, he was moved back downstairs to the ER.

State accountability

Before he lived in the hospital, Jack loved car rides.

He’d gaze out the window. And he liked the soft vibrations from the car, the muffled sounds of the outside world.

Several times a day he’d bring his mom her keys and shoes, begging for a ride. Once they drove to Oregon so Jack could get In-N-Out Burger — he likes drives, and he likes cheeseburgers! — so why not, Greta thought.

By November, Greta had removed the caged barrier from her blue Camry. Jack, she thought, wasn’t coming home anytime soon.

There are no quick fixes for kids in crisis, medical experts and policymakers agree.

“I don’t think any of us are comfortable with where things are at,” said Sue Birch, director of Washington State Health Care Authority. “But it really is, in my opinion, inaccurate or unfair to say we haven’t really been dedicating significant efforts on this issue over the four or five years I’ve been here. It has been one of our top priorities.”

But others say policymakers have consistently underinvested in youth mental health, even as more children went into crisis, racking up costly hospital stays and ballooning charges to government-paid insurance plans.

“The Legislature must respond, needs to recognize how and why we are here today, and course-correct,” Rep. Callan said.

During the pandemic, Washington received tens of millions in block grants from the federal government for behavioral health services. But to date, just over $1 million in those funds have gone toward youth behavioral health programs, state records show.

And a review of Department of Social and Health Services and Health Care Authority regular and supplemental budgets from 2017 until the present is testimony to several missed investment opportunities. Most years, additional dollars for children’s mental health came in the form of small, one-time, highly localized or pilot funds.

Officials also didn’t always follow through on budget priorities. In 2020, for instance, Gov. Jay Inslee vetoed $300,000 intended to fund training for youth mental health and substance use providers; HCA officials note that 2020 was a difficult budget year because of the pandemic and that federal grants helped support mental health training. Last year, lawmakers didn’t fund a request by DSHS for $1.1 million to expand substance use counseling at one of the state’s long-term youth mental health facilities.

2022 was an exception. Lawmakers created several new funding streams including $5.2 million for DSHS to build a crisis stabilization center for youth and expand in-home and outpatient services, and at least $25 million for HCA to support inpatient navigators and a partial hospitalization program, among other things. And heading into the next legislative session, solutions to the boarding problem are at the top of the list for the Children and Youth Behavioral Health Work Group, which advises the Legislature.