State takes over closed Burien facility, plans to serve kids in crisis

This story was originally published in The Seattle Times with support from the 2022 Data Fellowship.

A new government-run facility for youths with developmental disabilities is expected to open on Lake Burien in July. The state is leasing a set of cottages and administrative buildings owned by MultiCare.

(Provided by state Department of Social and Health Services)

A new government-run facility for youths with developmental disabilities is expected to open on Lake Burien in July. The state is leasing a set of cottages and administrative buildings owned by MultiCare.

(Provided by state Department of Social and Health Services)

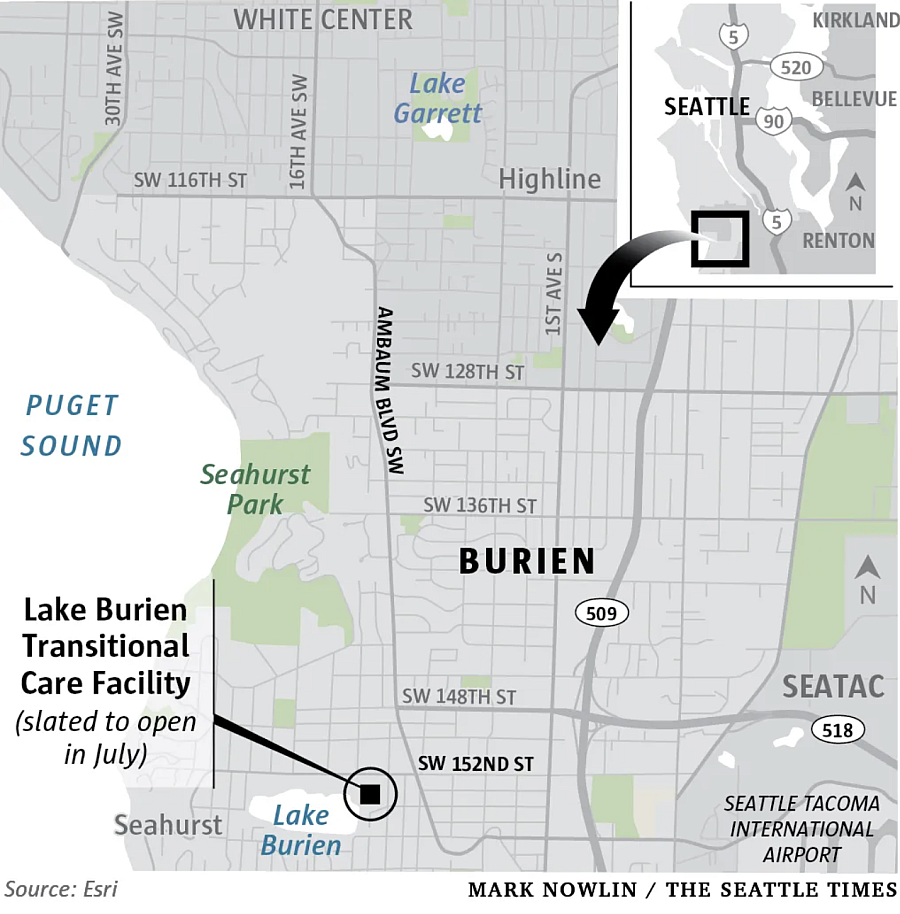

On the eastern shores of Lake Burien sits a grassy campus with a long legacy of housing Washington’s most vulnerable youths.

Nearly 100 years ago, the grounds were home to the Ruth School for Girls, a 30-bed residence for adolescent girls who’d become wards of the state. Decades later, the site housed kids of all genders in the foster care system. Most recently — and until its closure in 2021 — the property was a treatment facility for youths with serious mental illness or behavioral concerns.

The campus will reopen this summer with a new mission: serving youths who are among the hardest to treat within existing systems of care — those with neurodevelopmental conditions such as autism who also have so-called “co-occurring” psychiatric or substance-use disorders.

The 24-hour Lake Burien Transitional Care Facility is slated to open in July. Twelve residential beds will be available at first. The campus, which includes cottages with individual rooms, could eventually accommodate up to 36 youths.

It will operate under the auspices of the state’s Department of Social and Health Services and marks a novel approach by the state to directly care for youths who, because of the severity of their needs, have languished inside hospital wards and emergency departments because there was no better place for them to go. The move by DSHS follows a new state law that requires the Governor’s Office to coordinate care for kids who get stuck in hospitals.

Kids in crisis have long struggled to get access to the spectrum of services they need to stay stable. During the pandemic, youths began filling up emergency rooms at children’s hospitals across the state. Some spent days, weeks and even months locked inside hospitals as they waited for community-based services that allowed them to safely return home. Outpatient services materialized slowly, or not at all.

Washington has in recent years mostly relied on outside agencies — local hospitals, nonprofits and private providers — to offer psychiatric, behavioral and substance use services for youths. Public insurance such as Medicaid covers costs for some people, and the state operates a limited number of behavioral health beds while contracting with outside agencies for others. The result is a patchwork of care that’s ebbed and flowed at the whims of organizations mostly outside the state’s control.

Youths with developmental disabilities often require special services that have been especially hard to come by. Having autism, for example, can disqualify someone from treatment at certain residential facilities. Many families have turned to last resorts, including taking their kid to the ER or sending them to programs outside the state.

The new DSHS-run site is a move by the state to take more responsibility for this hole in services.

“It was a big gap in the whole continuum of care,” said Dr. Upkar Mangat, deputy assistant secretary for DSHS’ Developmental Disabilities Administration.

People ages 13 to 18 will have a chance to stabilize and gain skills so they can return to live with their families or in a supportive living facility, state officials say. There’s no time limit on how long youths can live there, though stays are supposed to be temporary.

It’s voluntary — the cottages won’t be locked, and youths opt into the kinds of care they receive. Its setting overlooking a lake and its menu of therapeutic services is expected to stand in stark contrast to the sterile, secured environs of a hospital ward. A high staff-to-patient ratio is intended to keep youths safe and ensure they receive specialized, intensive services.

The Burien campus was most recently home to one of the state’s most intensive psychiatric services for youths: the Children’s Long-term Inpatient Program. Operated by a MultiCare Health System subsidiary called Navos, the site was called Sunstone and offered residential treatment to those with serious psychiatric and substance use concerns.

Facilities such as Sunstone have struggled to stay afloat: staff turnover is high and state reimbursement rates are low. Facing those and other challenges, Sunstone decided to close in 2021.

“It was something that was tough for our organization because we really tried hard to keep the program up and running,” said Samantha Clark, assistant vice president of strategy and business development at MultiCare. “That’s partially why it’s been such a priority for us to figure out how to utilize that space.”

MultiCare owns the property, which includes three waterfront cottages built in 2014 and two additional buildings with office space, classrooms, a library, a kitchen and therapy spaces.

DSHS has signed a lease through February 2029, officials said; a total of $15.3 million in state and federal money will cover initial operation costs, Mangat said.

The state anticipates hiring about 98 staff, including a psychiatrist, nurses, occupational therapists, speech and language pathologists and other highly trained specialists. Youths will continue their school work while they live at the facility.

“We are calling it a transitional care facility for a reason,” Mangat said. “We don’t want youth at that age to come here and be institutionalized.”