Changing immigration policies could spell bad news for Valley's doctor pipeline

This reporting was undertaken as part of a project with the USC Center for Health Journalism’s California Fellowship.

Pharmacists are now poised to ease physician shortage—if only they could get paid for it

With limited federal funding, Valley struggles to expand medical training programs

When it comes to doctor access, the San Joaquin Valley is being left behind

Dr. Olga Meave sees a patient complaining of shoulder pain. After graduating from medical school and seeing patients in her home country of Mexico, Meave is now a third-year resident at the Rio Bravo Family Residency program in Bakersfield.

As the San Joaquin Valley struggles with a shortage of primary care physicians, one group in particular is stepping in to fill in the gaps: doctors born or trained in foreign countries. And while the planned repeal of the DACA program is President Trump’s most recent immigration policy change, he’s hinted at others that could influence the flow of foreign physicians into the Valley. This installment of our series Struggling For Care explores the valley’s complicated relationship with international doctors.

Dr. Olga Meave is a third-year family medicine resident in Bakersfield. She spends most of her time with patients in a Clinica Sierra Vista health center on the outskirts of the city.

Meave was born in northern Mexico. From a young age, she aspired to be a doctor—like her mother. But she wanted to practice in the U.S. After a high school exchange program in New York, Meave attended medical school in Guadalajara before returning to the U.S. Though she was already a practicing physician in her hometown, she had to be recertified in the U.S. She remembers the day she found out she had matched at the Rio Bravo Family Medicine residency program. “Happiest day of my life, yes, by far,” she laughs.

She became a U.S. citizen this past spring. After she graduates next year, she plans to stay in Bakersfield. “It's not the prettiest, but I felt comfortable,” she says of the first time she saw Bakersfield. “It reminded me of home in a way. The weather, the people, and I like it.”

A spreadsheet in a common room displays the schedules of all 18 Rio Bravo family medicine residents. Like Meave, the vast majority of the program's residents are international medical graduates.

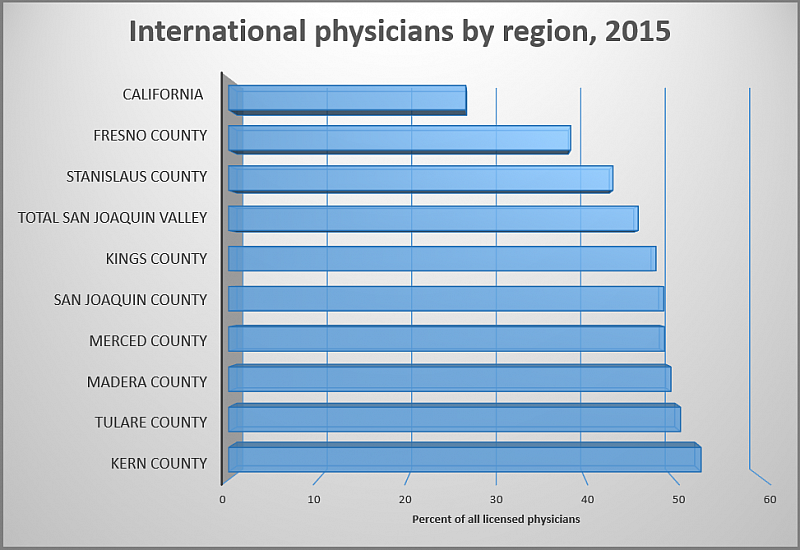

Throughout California, roughly 27 percent of all doctors are international medical graduates (IMGs), like Meave. Here in the Valley, that number is nearly 50 percent. Many are incentivized to practice in underserved communities like ours—but they like it here and they stay, filling a critical need in areas overburdened with disease and short on physicians.

“Whether you look at the residency fellowship system, the faculty at the university, whether you look at the Veterans Administration hospital, Kaiser Permanente, private practice, you will find an enormous contribution by foreign medical graduates,” says Dr. Sanjay Srivatsa, a cardiologist from the United Kingdom and director of the Heart, Artery and Vein Center in Fresno.

Our reliance on these IMGs also leaves us vulnerable to changes in immigration policy—which many worry could disrupt the pipeline of doctors into the Valley and leave it hurting for doctors more than it already is. “I would venture to say that if you removed all foreign medical graduates or foreign trained graduates from the system here in Fresno, it would collapse” Srivatsa says.

You don’t have to go far to find a physician educated in one of the 87 countries represented by doctors in the southern San Joaquin Valley. Dr. Jorge Martinez is from Colombia, and is a hospitalist with Community Regional Medical Center in downtown Fresno. “We have people from Bulgaria, we have people from Eastern Europe, we have people from Asia, Cambodia, Vietnam, Nigeria,” Martinez says of his physicians group. “It's like the mini United Nations—we are like 26 countries.”

Medical Board of California, UC San Francisco

The biggest suppliers of physicians are India, Caribbean nations, and the Philippines. IMGs are more likely to practice in primary care—where the Valley has 35 percent fewer physicians than the government recommends. Many of our Spanish-speaking international doctors are graduates of a UCLA program that helps IMGs pass exams and land residencies, in exchange for working for a few years in medically underserved areas.

The U.S. government also makes these regions attractive. When IMGs come to the U.S., no matter how much experience they have, they’re required to complete a residency before they can legally practice. To do this, most get a J-1, or foreign exchange visa. When it expires, they’re required to return home—unless they spend three years working in an underserved area.

After the J-1, foreign doctors commonly move on to an H-1B visa. That program brings in specialty workers ostensibly for jobs that Americans can’t fill. After a certain number of years on the H-1B, doctors can then apply for permanent residency and a path to citizenship.

But this spring, President Trump hinted at changes to this pathway. He signed an executive order in April calling for an independent review of the H-1B program. “Right now, widespread abuse in our immigration system is allowing American workers of all backgrounds to be replaced by workers brought in from other countries to fill the same job for sometimes less pay,” he recited during a speech in April.

Deepak Ahluwalia is an immigration lawyer in Fresno. He says, sure, the H-1B program could use some improvements, but too many physicians is not the problem. “If we specifically talk about doctors, that policy won't work, because as we've discussed, they're having a problem hiring doctors here or finding doctors here,” he say.

Before the executive order, the administration had already made one change: It revoked expedited processing of H-1B applications. Ahluwalia doesn’t know what happened locally, but elsewhere, some IMGs were forced out of the U.S. because they couldn’t get visas quickly enough to hold on to job offers. “So it didn't work out too well this time, they reinstated it after realizing the huge blunder,” he says. “One can only hope that any other policies they think of in the future, they're actually going to consult with doctors, they're going to consult with areas that are designated by the government to be underserved.”

A few weeks ago, the Wall Street Journal reported the Trump administration was also considering restricting the J-1 visa program, but no specifics have emerged.

Even if immigration policies remain unchanged, many health leaders worry recent anti-immigrant rhetoric could be enough to scare away international doctors and aspiring doctors. Among those is Michael Peterson, associate dean of UCSF Fresno. Right now, 31 percent of the school’s medical residents and fellows are IMGs. “They're roughly a third of our trainees,” he says. “And so to lose that number would be a significant deficit in terms of the physicians we'd be putting out into the communities.”

There’s no indication yet that doctors elsewhere are thinking twice about emigrating to the U.S. Applications for H-1B visas did drop this year, but it’s too early to determine why and if it’s a trend. Nevertheless, most health authorities I spoke to said waning interest from international doctors is a major concern.

Back in Bakersfield, Olga Meave points out: If she had been looking to undercut American jobs, this was not an easy way to do it. To practice here, doctors like her have to repeat years of training and exams they already completed in their home countries. “I knew it was extremely competitive and hard, but I really wanted it,” she says.

Now, the U.S. government will have to decide how much it wants international doctors.

[This story was originally published by Valley Public Radio.]

[Photos by Kerry Klein / Valley Public Radio]