Cherokee Nation offers a 'judgment free zone' for Oklahomans facing addiction

The story was originally published in KOSU with support from our 2021 National Fellowship.

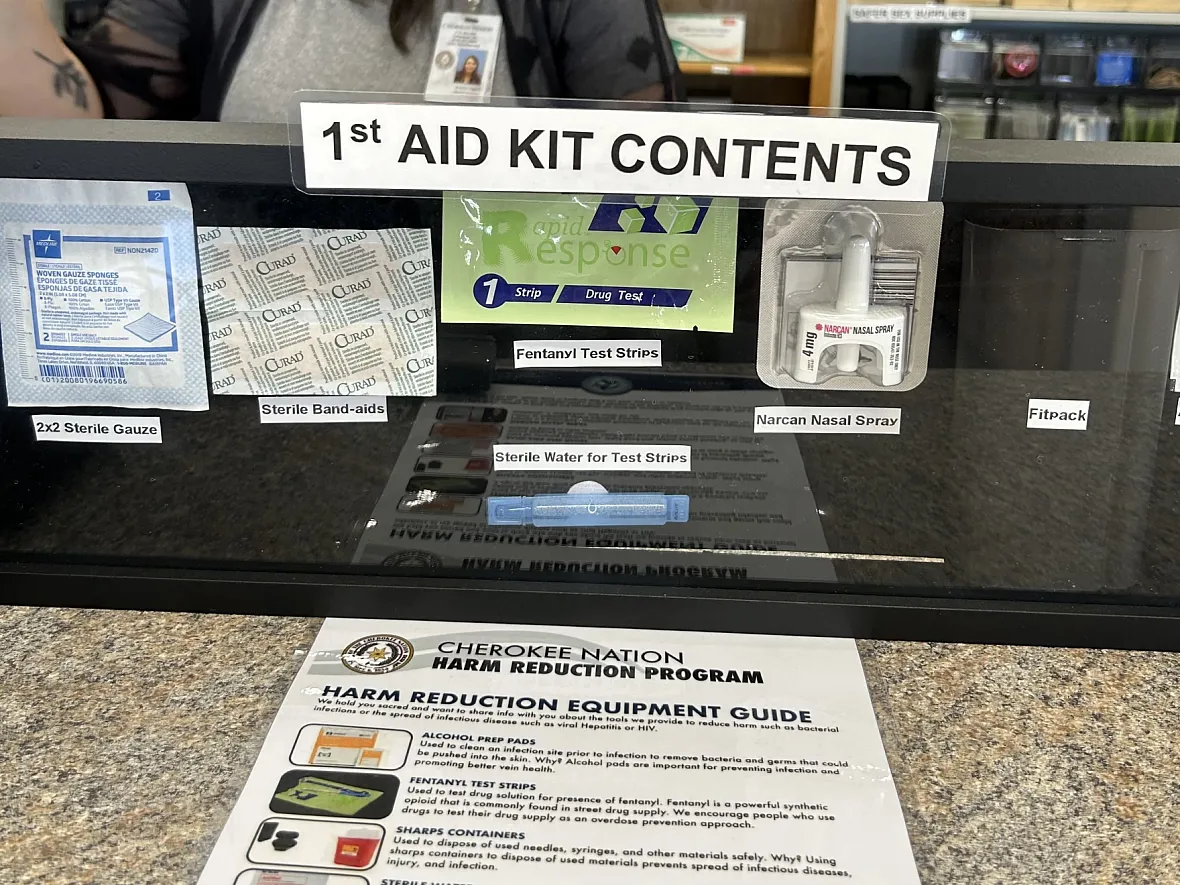

Cherokee Nation is giving out harm reduction kits in Tahlequah to help people facing addiction.

Allison Herrera/KOSU

Cherokee Nation's Harm Reduction Center is meant to evoke a comfortable atmosphere for people dealing with issues related to addiction.

Allison Herrera/KOSU

The first thing that greets visitors at Cherokee Nation's new harm reduction center in Tahlequah is a comfortable couch and table right next to a pot of coffee and snacks.

Although the people that end up inside this low slung brick building near W.W. Hastings Hospital may not be looking to warm up on a chilly February morning, the option is there.

"We welcome people with unconditional positive regard," said Coleman Cox, who is the program supervisor for the harm reduction program.

Harm reduction is a model of public health that some say dates back to the 1960s when Black Panthers in Oakland, California provided food and free medical care for members of the community. Today, it's helping people reduce the risk of contracting serious diseases like HIV and hepatitis C by giving them clean syringes and providing them with some necessities. And even though it’s run by the Cherokee Nation, it’s open to everyone.

The Cherokee Nation is using a holistic model to fight addiction in Northeast Oklahoma.

The center is part of a much broader $100 million dollar investment made possible by a Public Health and Wellness Act Principal Chief Chuck Hoskin Jr. passed in 2021. It will also be funded through a $75 million settlement reached with opioid drug manufacturers McKesson, Amerisourcebergen and Cardinal Health.

If people want counseling to get sober, the center has a peer support specialist on site to help. If they don't need that, then staff like Brittany Huggins are there to offer everything from condoms, clean syringes to first aid kits containing Narcan spray, to hygiene products like soap, toothbrushes and tampons. All of it is offered for free.

Cox said the program is about meeting people where they're at and offering them the tools to stay safe when making choices to use or get sober.

"Everybody comes here at a different level and a different readiness for different types of services,"Cox said.

"And so the way that we practice harm reduction is by creating that judgment free zone. We provide people with the equipment they need to prevent further harm from the choices that they do make."

Their biggest concern is reducing the risk of overdose, especially from fentanyl, which is why they offer test strips to let people know if their product contains the deadly substance. The strips are included with the kit that people can pick up. They allow people to test drugs they might be using to detect fentanyl and reduce risk of overdose.

Cox says the strip is not 100% accurate, but it's a start.

"It's a tool that we can use…it helps us to make an informed decision: Do we use, or do we not use," said Cox

Cox has heard criticism of the harm reduction model – that it's enabling people – but he says that's not supported by studies that have been done by groups like the National Institutes of Health.

"When you start to see people who have been using substances like heroin or fentanyl for years, start making life changes, start turning their life around, reducing harm, when we start seeing that, it's going to change the perspective in the narrative," he said.

The program had a soft opening last fall and has nearly 100 members who return to exchange needles or pick up supplies. This is a place for anyone to come for both addicts and non-addicts.

Brittany Huggins works for Cherokee Nation and gives out harm reduction kits to people in the Tahlequah community.

Allison Herrera/KOSU

Brittany Huggins' family has been impacted by addiction. Her cousin overdosed, and her brother is an active methamphetamine user. She told him about the harm reduction center, but he lives outside of Tahlequah, and she's not sure he would be able to make the trip there.

"But if he asked me, I would definitely give him some syringes or anything if he asked," Huggins said.

Soon, he may not have to come to Tahlequah to receive supplies and support to get sober. The center has plans for a mobile harm reduction unit that will drive across Cherokee Nation’s 14-county reservation, part of meeting people where they're at.