In combating the Valley’s high teen birth rates, what about teen fathers?

This story, part of a series about sex education and teen pregnancy, was produced as a project for the USC Center for Health Journalism’s California Fellowship.

Other stories in the series include:

Here’s what Fresno high school students say they’re learning about sex

We asked 20 women what they wish they had learned in sex ed class

Teen birth rates are highest in our poorest neighborhoods. But they affect all of us

Sex education is now the law, but conservative school leaders aren’t happy about it

Why are birth rates higher for Latina teens than others? It’s complicated, experts say

This teen mom and her newborn rode a city bus to a school for delinquents. Here’s why

At 14, she was told to hide her baby bump and switch schools. Her shaming wasn’t unique

After reading teen mom’s story, strangers wanted to help. And they delivered.

Three-year-old Emma gets in one more last-minute hug with her dad, 18-year-old Kevin Aguilar, after he drops her off at day care before he begins his day at Fresno’s School of Unlimited Learning. John Walker

Kevin Aguilar was late to class again.

He and his 3-year-old daughter, Emma, had missed the city bus, making her late for preschool – and him even later for high school.

“In the mornings, it’s a rush. I’m always looking for her shoes,” said Aguilar, 18. “She likes to take them off.”

Aguilar has full custody of Emma, and says he knows he isn’t the typical teen father.

“The guys, they feel like they have more freedom, I guess. They feel like they get to go out and do their own thing and come visit once in a while,” he said. “I don’t worry about that much because I get to hang out with Emma. She’s kind of like my best friend now.”

Half of California’s 10 counties with the highest teenage birth rates are in the Central Valley, despite statewide and nationwide record lows in teen births. A state law that went into effect last year mandates comprehensive sex education aiming to curb those rates, and requires schools teach about contraception, abortion, sexual consent and more.

"The norm with teen pregnancy is the father isn’t going to stick around. It’s accepted and rationalized so it’s continued." — Carlo DeCicco, health educator for Fresno Barrios Unidos

But the Valley lacks programs for teen dads and isn’t doing enough to help boys understand the responsibilities of sex and young parenthood, according to Carlo DeCicco, a health educator for Fresno Barrios Unidos.

“The norm with teen pregnancy is the father isn’t going to stick around. It’s accepted and rationalized, so it’s continued,” said DeCicco, who mentors teen fathers as part of his work. “It’s not as easy for a young mom to walk away from her duties. So you hear about (teen fathers) as secondary people in the story, and that hurts the teens who are trying to maintain a relationship with their child because it means they’re not equally worth investing in.”

Not like the rest

When he found out he was going to be a father at 15, Aguilar started working on the weekends as a cook at a Fresno nightclub. His Saturday shift didn’t end until 5 a.m. Sunday, making Mondays at Fresno High School tough.

“I was falling asleep in classes. That’s how I got behind in credits,” he said.

Now, Aguilar is a student at the School of Unlimited Learning (SOUL) – the city’s oldest charter school, located next door to a homeless youth shelter operated by the Fresno Economic Opportunities Commission.

SOUL serves “high-risk, disadvantaged youth,” and offers more flexibility in scheduling. That means Aguilar can start first period later than usual, and take care of Emma, with teachers and administrators who he says are more understanding of his struggle than those at a traditional school.

Three-year-old Emma plays with her father, 18-year-old Kevin Aguilar, at Sequoia Head Start before he heads to class at the School of Unlimited Learning. John Walker

“Kevin is different. We always praise him for doing the right thing,” said Michael Potts, a case manager at SOUL for 15 years. “Most guys just don’t step up. So we try to provide him with as many services as possible, whether it’s employment training or daycare expenses. We’ve got good kids here like at any other traditional school, but they are kids who have fallen off, and it’s our job to get them back on track.”

Barely considered an adult, Aguilar refers to the other dads he sees dropping off their children at daycare as “the grown-ups.” But he’s come a long way since Emma was a newborn. His advice to young dads who feel they don’t know what they’re doing: breathe.

“Try to stay calm,” he said. “At first, you get frustrated a lot because you don’t know what they want. But it gets easier. You get to know them – what they need when they’re sick, when they need to go to sleep. If you get upset, they’ll get upset, too. So relax.”

After a handful of court dates, Aguilar successfully won custody of Emma. He said Emma’s mother’s “living situation isn’t all that good,” and that she didn’t show up to several of the court dates in which he was vying for sole custody.

His father died when he was young, and his own mother – an immigrant from El Salvador – has been a big support for him. But he still worries about Emma growing up with a single parent.

“I only grew up with one parent, so I feel like she’s going to feel how I felt. Like when the schools have a Father’s Day, I was always by myself,” he said. “I want to break the cycle. I don’t want her to get pregnant. I want her to have the opportunities I didn’t have.”

Breaking the cycle

Johnny Baltierra talks about “breaking the cycle,” too. He was a senior at Fresno High in 1976 when he found out he was going to be a father.

“At 17, I thought I was about to become a soccer star, a cross country star. Instead I became a daddy,” said Baltierra, who now works as a counselor at Parkview Middle School in Kings County.

Baltierra, 58, said his dad stayed in Mexico when he and his mother moved to the U.S. when he was 3 years old. His stepfather was abusive to his mother and “no role model,” he said, so he never had a father figure.

When he found out more than 40 years ago that he and his girlfriend, Susan, now his wife, were about to become parents, he vowed not to repeat history.

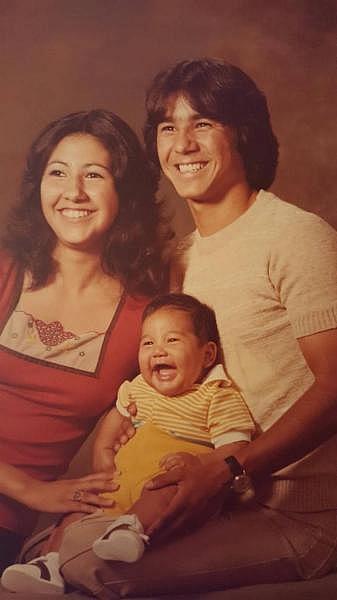

Johnny Baltierra, seen here as a Fresno High student, poses with his wife, Susan, and their 1-year-old son, Michael, in 1977. Submitted to The Bee

“I thought that’s it: I want to be the dad I never had,” Baltierra said through tears. “I said, ‘We’re going to make it.’ I’m not going to be poor. No food stamps, no field work for me. My kids are going to have a totally different life.”

As a teen, Baltierra cared for their first child, Michael – who is now 41 – while Susan Baltierra attended nursing school. As a school counselor, he shares his story with his students and is aiming to get boys to change their perception of manhood – and to be more involved in the conversations about abstinence, safe sex and parenting.

“We need to continue to tell the guys to respect the girls, and to say that if they’re going to do it, then they need to be responsible and make wise choices. It takes two,” he said. “That’s what’s going on with a lot of our guys – their own dads aren’t stepping up. I tell them you’ve got to commit, because very few boys do.”

A systemic change

Nearly 25 percent of Fresno County families are headed by single mothers, higher than the state average. Only about 5 percent of Fresno County families are single father households. Nationally, when it comes to single parent households, more than 80 percent of the time it’s mothers who are the caretakers.

These statistics create a conundrum for outreach focused on teen fathers. Barrios Unidos has been the most active pregnancy and STD prevention organization for youth in Fresno for decades, but has no grant-funded program specifically for teen dads.

“There’s been a lot of money invested in teen moms, which is good and needed because they bear the responsibility. But that funding and those services aren’t easily available for teen fathers,” DiCicco said. “That conflicts with the teens who are trying to maintain a relationship with their children. It’s an uphill battle at times when they do want to be actively involved.”

"We have to start by dispelling myths and perceptions about sex education. I think a lot of people believe it’s a how-to rather than that it’s coming from a medical standpoint." — Cristie Granillo, program manager for Positive Prevention Plus

Cristie Granillo, program manager for Positive Prevention Plus, which helps teach sex education courses at Fresno Unified, has been approached by teen fathers who don’t even realize they have a right to see their child.

“I tell them it’s not only your right, but it’s your responsibility,” she said. “Those stories are there, but there’s not a microphone for those fathers.”

To provide more focus on teen dads, it’s going to take time to shift years of oppression of women, Granillo said, but getting comprehensive sex education in schools – for all genders – is a first step in changing the system.

“This is something that historically men have not had to think about. It’s injustice rooted in male privilege,” she said. “I think oftentimes when policy is created, it’s reactive rather than proactive. We have to start by dispelling myths and perceptions about sex education. I think a lot of people believe it’s a how-to rather than that it’s coming from a medical standpoint: ‘Here are the facts and your options and how you prevent these situations from happening in the first place.’ They need to understand what’s at stake.”

Sarah Hutchinson, policy director for ACT for Women and Girls in Visalia, said reproductive justice organizations like hers would love to support young fathers, but they don’t have the funding or the capacity.

“Young dads get a bad rap, and are so often stereotyped. There absolutely isn’t enough support out there for them to explore healthy masculinity, being a 50-50 parent partner, etc. And we know there are young dads out there that want this support … ” she said. “The lack of investment in young dads often stems from broader gender expectations about who gets to parent, and who gets support to be a parent, which is often the mother.”

[This story was originally published by The Fresno Bee.]