As commercially insured patients pay more to hospitals and clinics, lawmakers fail to pass a local senator's bill expanding oversight of the health care industry (Part 2)

This article was produced as part of a 2019 Data Fellowship with the USC Annenberg Center for Health Journalism.

Editor’s note: This article is the second of a two-part series produced as a data fellowship with the USC Annenberg Center for Health Journalism. The first part, “Consolidated,” published on Sept. 10.

Annual hospital financial reports highlight one big-picture health care trend across California: Hospitals are making increasingly higher profits on commercially insured patients, while they’re suffering steeper losses on Medicare patients.

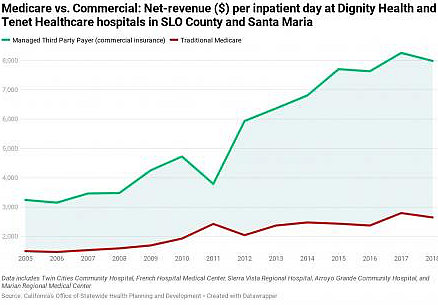

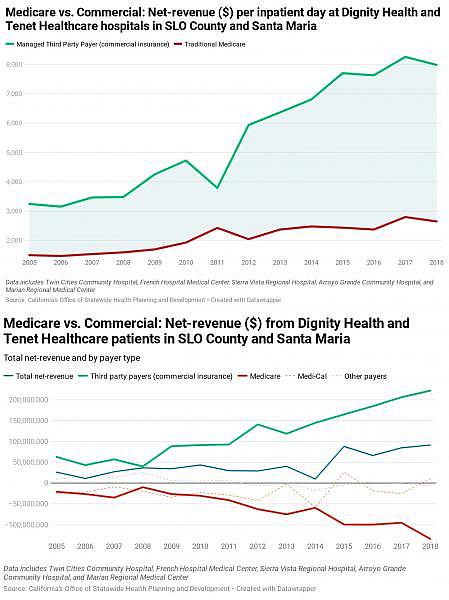

Many experts blame hospital industry consolidation for that growing disparity—and the Central Coast is no exception. A Sun analysis of hospital data for Northern Santa Barbara and San Luis Obispo counties found that between 2005 and 2018, hospitals’ net-revenue on “third-party payers” (or commercially insured payers) shot up 354 percent, while its net losses on Medicare payers plummeted 641 percent.

State hospital data shows a growing disparity between what hospitals earn off private insurance compared to government plans like Medicare. In 2018, Northern Santa Barbara and San Luis Obispo county hospitals made 3.5 times more profit from commercial insurance payers than they did in 2005, up to $222 million, while they lost more than $130 million on Medicare patients, down six-fold from 2005. - GRAPHS CREATED BY PETER JOHNSON ON DATAWRAPPER

Looked at another way, for every inpatient day logged at local Dignity Health- or Tenet Healthcare-owned hospitals during 2018, providers made three times more revenue if that patient was privately insured versus if he or she was on Medicare.

When asked why patients with commercial insurance are charged so much more, Arroyo Grande resident Jamie Maraviglia had a simple answer: “Because they can.”

Maraviglia’s daughter, Ara, suffers from Hirschsprung disease, a rare intestinal illness that requires periodic hospital stays, which produce expensive medical bills for the family.

“The hospitals have the leverage,” Maraviglia told the Sun. “There’s a reason our premiums keep going up.”

While Dignity and Tenet officials declined to comment, health care experts and insiders have differing views on the development. Critics of hospitals and their growing monopolies in communities say they are simply price gouging commercial insurers to make more money. Hospitals, though, argue that Medicare has failed to keep up with their expenses over the years. Others say that the hospitals are simply spending too much and now have little choice but to charge the groups they have control over.

“We have this unbalanced system,” explained Jay Gellert, the former CEO of Health Net insurance, “where these guys really do have to chase the limited number of commercial patients in order to be economic.”

In 2010, Gellert was part of an insurance industry team that assisted the Obama administration with the development of the Affordable Care Act. Gellert said that while the act gave insurance to many Americans, it also left the door wide open to more consolidation.

“They basically encouraged consolidation of hospitals, hospitals buying up physician practices, the theory of integration, but there was no accountability behind it,” he said. “They had no cost containment in the system.”

Gellert said that the consolidation phenomenon is inherently anticompetitive.

“Just like in much of America, companies have learned that true competition is hard, and it’s a lot easier to consolidate and have some ability to limit price competition,” he said.

David Palchak, who has an independent oncology practice in Arroyo Grande, said he experiences those anticompetitive effects firsthand—receiving no more than Medicare rates from commercial plans. Every year, Palchak writes to Blue Cross and Blue Shield to make an offer: If it paid him 30 percent above Medicare, he would be able to grow his practice and expand services throughout the community—while saving patients and health plans money.

He’s yet to receive a response.

“If they would contract with me at this rate, I could provide all cancer care for the community as I would have enough money to expand throughout the region,” he said.

State bill regulating hospital mergers dies

While some Californians call for major national health care reform, like Medicare for all, as a solution to rising medical bills, state lawmakers have tried advancing more nuanced legislation aimed at controlling costs and preventing anticompetitive behavior.

Assembly Bill 3087, which was proposed in 2019 but killed, would’ve established a commission to oversee and put ceilings on commercial insurance payments to medical providers.

This year, Sen. Bill Monning (D-Carmel) introduced Senate Bill 977, which would’ve given the Attorney General’s Office oversight of for-profit hospital mergers and acquisitions. Currently, the attorney general only has purview over nonprofit hospital transactions. It would’ve also carved out new enforcement mechanisms for the attorney general to fight anticompetitive behavior and established a Health Policy Advisory Board to analyze California health care markets.

“The basic mantra is patient protection,” Monning told the Sun in July. “When you have larger systems that may seek to acquire a solo hospital or other types of medical services of a certain size, the goal is to make sure patient services are protected.”

But despite the bill passing the Senate floor and multiple Assembly committees, the full Assembly declined to take it up for a vote prior to a Sept. 1 legislative deadline—which means the bill died. It had received substantial opposition from the California Hospital Association and other health care provider groups.

“The outcome of SB 977 today represents a win for the large health care conglomerates that monopolize the health care marketplace,” Monning said in a statement on Sept. 1. “We have failed to protect Californians and failed to protect their right to affordable, accessible health care from anticompetitive, market manipulation.”

Tenet Healthcare, the national for-profit chain that owns two hospitals in SLO County, was among the hospital players to come out against the bill. In a July 2 letter to the state Assembly Health Committee, the company’s four California CEOs said the bill would’ve created “a presumption that these transactions are anticompetitive, ... creating a ‘guilty until proven innocent’ system.”

“There are many reasons hospitals merge or affiliate,” the CEOs wrote, “including to preserve and expand access to care across the communities they serve, introduce new services, coordinate and integrate the delivery of services, create centers for excellence for complex procedures, better support nurses and physicians, and more.”

The executives said the bill would’ve hampered hospitals’ mobility as they struggle with COVID-19 and its fallout.

“The timing for SB 977 couldn’t be worse, as California hospitals of all sizes are already struggling under the enormous strain and financial impacts in meeting the generational challenges associated with the COVID-19 pandemic,” the letter read. “Such mergers, affiliations, and related transactions can be not just timely, but vital to preserving a safety net and access to care for residents of these particular communities.”

Monning countered that the instability created by COVID-19 made his bill even more timely and important.

“The opposition said, now with COVID-19 and the economy in distress, this really isn’t a good time to do this. My response is just the opposite,” he said. “Because of COVID-19, you have some systems that are in economic distress and could be susceptible to a large hedge fund that could see an opportunity to make a quick, below-market acquisition without any commitment to the local community.”

Jaime King, a law professor and health care policy expert at UC Hastings College of the Law, echoed this concern and said it could exacerbate the effects caused by hospital consolidation.

“COVID-19 has put a massive strain on small hospitals, on physician practices,” King told the Sun. “People are going to the doctor less. The remaining independent entities are looking at either closing their doors or selling to a big hospital system that’s going to allow for an influx of cash for them. I think we’re going to see a lot more consolidation come out of this.”

Maraviglia, the mother of Ara in Arroyo Grande, said that she’ll continue fighting for a future that gives families like hers access to more affordable health care.

“I think once you’re actually part of the system, you go, ‘This is so messed up,’” she said. “It moves people into bankruptcy and financial distress, just because they want to live. They don’t want their kids to get sick.

“We’re trying to keep our kids alive.”

You can reach Peter Johnson, assistant editor of the Sun’s sister paper, New Times, at pjohnson@newtimesslo.com.

[This story was originally published by Santa Maria Sun].