Congenital syphilis rates soar across California as public health funding dwindles

This story was originally published in CalMatters with support from the 2022 California Fellowship.

STD Investigator Hou Vang (left) works in his office as Jena Adams (right), Communicable Disease Program manager, checks in on him on June 8, 2022.

Photo by Larry Valenzuela, CalMatters/CatchLight Local

In the Central Valley, where two-thirds of the nation’s fruit and nuts are grown, the pastoral landscape masks entrenched racial and economic disparities. Life expectancy in Fresno County drops by 20 years depending on where you live, and it’s those who live in historically poor, redlined or rural neighborhoods who are most impacted by a resurgence of maternal and congenital syphilis.

“Are you familiar with syphilis?” Hou Vang, a county communicable disease specialist, asks a pregnant woman standing in the shade of a tree outside her home.

She lives with her parents in Reedley, California, a small town 30 minutes southeast of the city of Fresno, surrounded by neat rows of grapevines, orange groves and almond trees.

“I mean, you hear things,” she says, distractedly eyeing a family member’s car pulling into the driveway. The woman allowed CalMatters to report on her diagnosis on the condition of anonymity.

“It’s an STD (sexually transmitted disease). We like to disclose in-person in case there are any questions,” Vang says. “You did test positive.”

“Oh my god,” she breathes, tearing up. “I have a lot of questions for my kid’s dad.”

STD Investigator Hou Vang drives to a rural town in Fresno County to make a home visit with a pregnant patient and provide them with information on July 14, 2022. Vang says many of his patients struggle to get to the nearest hospital that can provide treatment for syphilis.

STD Investigator Hou Vang speaks with a pregnant patient to inform them of their diagnosis and provide information on July 14, 2022. Photos by Larry Valenzuela, CalMatters/CatchLight Local

Vang works for the county health department, where he’s on the frontlines of California’s fight against maternal and congenital syphilis. Rates of infection have ballooned to numbers not seen in two decades. Congenital syphilis occurs when the infection is passed from mother to baby during pregnancy. If untreated, the infection has devastating consequences, causing severe neurological disorders, organ damage, and even infant death. In few places is it worse than California’s Central Valley. Fresno was the first county to sound the alarm, alerting the state health department in 2015 when the number of cases more than doubled in one year.

It has only gotten worse since then. Today, California has the sixth-highest rate of congenital syphilis in the country, with rates increasing every year. In 2020, 107 cases per 100,000 live births were reported, a staggering 11-fold increase from a decade prior. That rate far exceeds the California Department of Public Health’s 2020 target to keep congenital syphilis numbers below 9.6 cases per 100,000 live births — a goal it outstripped almost as soon as it was set.

Even more shockingly, the syphilis rate among women of childbearing age was 53 times higher than the 2020 goal.

At one point in the late 1990s, rates were so low across the U.S. that the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention thought syphilis among men and women could be effectively eradicated from the population. After all, in many cases a single shot of penicillin is all that’s needed to curb the infection. But at both the national and state level, public health departments were overstretched and woefully underfunded. People slipped through the cracks, and sexually transmitted infections of all types began to skyrocket once more.

Increasing case rates have also gone hand-in-hand with increasing rates of homelessness and methamphetamine use. Inadequate prenatal care is the No. 1 predictor for maternal and congenital syphilis. It is a disease whose reemergence signifies severely inadequate access to health and social services systems.

“When they rank developed nations on health measures, the indicators always include sexually transmitted diseases,” said Dr. Mohammad Nael Mhaissen, a pediatric infectious disease specialist at Valley Children’s Hospital in Madera. “And we’re failing.”

This should ‘never’ happen

Vang knows when he has found a meth den. The sharp, acrid scent of the drug is unmistakable — it smells like cat pee.

He’s had doors slammed in his face and a gun flashed at him once. He takes it all in stride, accepting that many people are wary when a government vehicle pulls up in front of their home. His job is to track down people who have tested positive for sexually transmitted infections, and his most urgent cases are pregnant women who have syphilis.

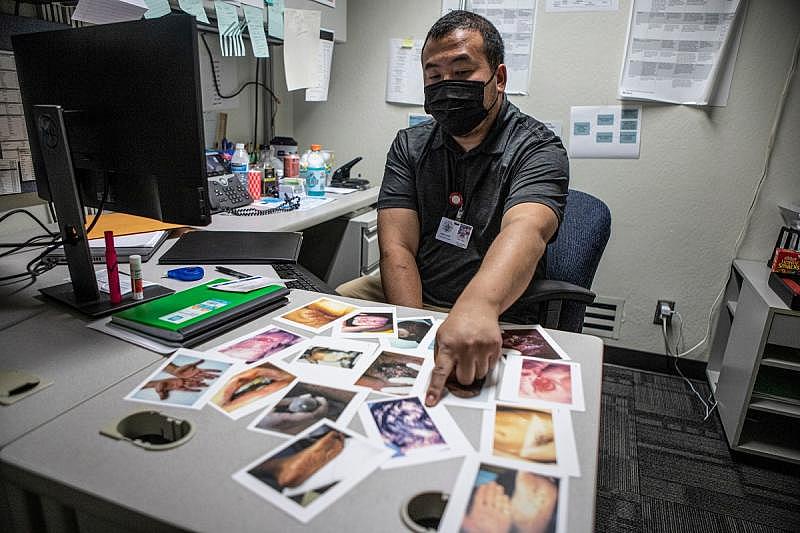

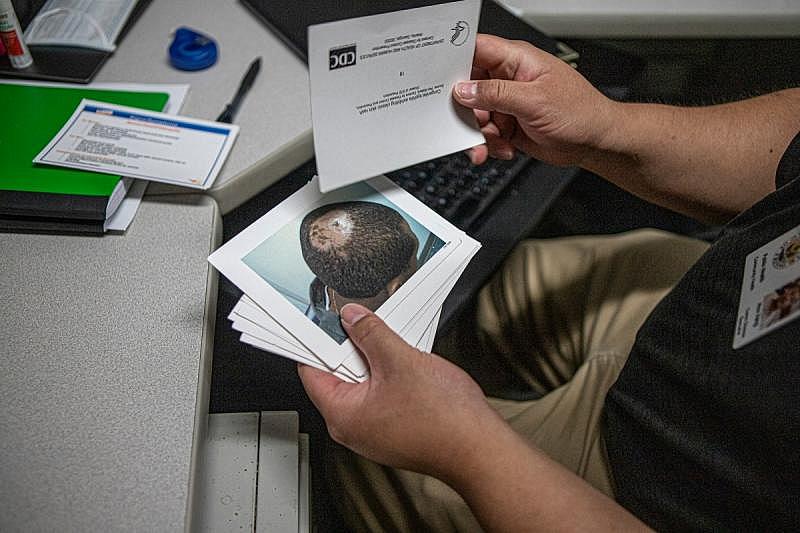

Vang carries with him a stack of postcards issued by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control with pictures of syphilis symptoms to ask clients if they’ve noticed any of the signs. The images are graphic, showing male and female genitals pock-marked by bumps, a newborn covered in a rash, and a man losing his hair. But the infection is also easy to misdiagnose, especially when a whole generation of physicians have gone their entire careers without seeing the so-called dead disease.

Hou Vang shows the postcards issued by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control with pictures of syphilis symptoms he carries to show patients what syphilis symptoms can look like on June 9, 2022.

Hou Vang shows the postcards he carries to show people what syphilis symptoms can look like on June 9, 2022. Photos by Larry Valenzuela, CalMatters/CatchLight Local

Medical historians call it “the great imitator” because the symptoms are commonplace and disappear after a few weeks even though the body still carries the bacteria. Women in particular may never notice the painless bumps of early infection until it comes back months or years later to wreak havoc on their internal organs. Too often, women aren’t diagnosed until they’re well into their pregnancy, when the infection can cause severe physical and cognitive disabilities for the baby, attacking their bones and nervous system. If untreated, there’s a 40% chance the baby will die.

In 2019, the most recent year detailed state data is available, 37 syphilis babies were stillborn and 446 were infected. Black babies were three times more likely to be born with syphilis compared to the statewide rate, while Hispanic babies made up nearly 50% of all cases. (Native American infants were not included in this calculation because numbers are too low to be statistically stable.)

It can be easy to blame women’s choices for increasing rates, but the truth is much more complicated. The CDC noted in its 2020 Sexually Transmitted Disease Surveillance report that “these disparities are unlikely explained by differences in sexual behavior and rather reflect differential access to quality sexual health care.”

Dr. Dominika Seidman is an obstetrician and gynecologist with Team Lily at UC San Francisco. Her group provides prenatal care and wraparound social supports such as housing navigation, substance abuse and mental health treatment for vulnerable women.

For a long time there were no cases in San Francisco, Seidman said. In 2020 there were five, but the low numbers are misleading. Even one case of congenital syphilis is known as a “sentinel event” in health care — an event so rare and preventable that its occurrence should ring alarm bells.

“This should be a never event,” Seidman said. “It is an absolute disgrace that we are even talking about congenital syphilis.”

It’s hard to pinpoint one reason for the resurgence of this and other sexually transmitted infections, which have also reached record-setting numbers, but high on the list is barriers to health care. In a recent study led by state health department researchers, babies born in the poorest census tracts in the state experienced congenital syphilis at 17 times the rate of those born in the most affluent census tracts.

“This is a reflection of holes in our safety net, and it’s a reflection of all the different social determinants of health that play into poor health outcomes,” said Dr. Ina Park, medical director for the California Prevention Training Center at UC San Francisco and co-author of the CDC’s 2020 sexually transmited infection treatment guidelines. Park was not involved in the study.

Those social determinants of health — or barriers such as housing instability or lack of insurance — lead to missed opportunities to stop the infection from spreading. In the first two years of California’s outbreak, between 2012 and 2014, nearly one-third of mothers who gave birth to babies with syphilis were never tested before delivery and one-third were tested less than 40 days before giving birth. In contrast, every mother who gave birth to syphilis-free babies was tested early in their pregnancy, according to state researchers.

Those disparities haven’t budged in the ensuing years. In 2018 more than half of pregnant women with syphilis had delayed or no prenatal care, according to a more recent analysis from the California Department of Public Health. Half reported methamphetamine use, and roughly half were recently incarcerated or homeless, the report said.

“It is structurally a socioeconomic issue — a race issue,” said Jennifer Wagman, a UCLA researcher who in 2018 oversaw a study in Kern County aimed at identifying why women were missing prenatal care.

“We’re not seeing wealthy white women with (congenital syphilis) babies. It’s just not happening,” Wagman said.

In the Central Valley in particular, language and distance create additional barriers.

One woman whom Wagman interviewed for her study said “You don’t make it to the appointments because it’s going to take too long on the bus or you won’t make it back in time to pick up the kids at school. You know transportation is a big, big issue.”

This is certainly true of Vang’s latest case in Reedley. He assures the woman that the infection is curable and that it’s lucky it was caught relatively early in her pregnancy, in her second trimester. But her case is complicated. She’s allergic to penicillin, the primary treatment option, and will have to be gradually desensitized to the antibiotic over time. She also has a seizure disorder and can’t drive, relying on family members for transportation. The only hospital that can treat her is Community Regional Medical Center in downtown Fresno, 30 minutes away.

“That’s a far drive. Plus the time for desensitization. That’s a whole day not only for her but for whoever drives her,” said Vang’s boss, Jena Adams. “That’s a barrier.”

They offer her a $20 ARCO gas card and $20 Walmart card per treatment in hope that it will help offset the cost of transportation.

How did we get here?

Back in central Fresno, Vang knocks on the front door of a single-story ranch-style house with a manicured lawn. The next-door neighbor comes outside and watches Vang with suspicion.

No one answers.

Vang tucks an envelope into the door jamb with the resident’s name on it and drives around the block before pulling slowly past the house again to see if anyone has taken the envelope, giving away that they are, in fact, home — they were not. It’s the second time he has visited the house in as many days. He’s looking for a young man who tested positive for syphilis several weeks ago with no prior history, an alarming trend that cropped up during the COVID-19 pandemic. Records show the man’s girlfriend is pregnant.

A month later, Vang will be back. Even though the man received a penicillin shot and claimed his girlfriend was treated, she hasn’t shown up in the county surveillance system, meaning she likely wasn’t tested or treated. She and her unborn baby need to be treated as soon as possible. Otherwise the baby will be held in the neonatal intensive care unit for 10 days of intravenous treatment, and even with that may suffer lifelong consequences.

Tracking down infected and exposed patients is labor-intensive. The most effective follow-up requires face-to-face interaction with investigators like Vang knocking on doors, visiting homeless encampments and shelters, combing through mental health and social services files for current addresses, and in some cases contacting family members or employers to track someone down.

But that work is expensive.

“The in-person time that’s required to prevent a single case is so labor intensive that it’s possible funding was not sufficient to effectively stamp this out,” UCSF’s Park said.

Prior to the pandemic, public health funding was notoriously low. In the decade following the 2008 recession, state funding for public health dropped by 64%. Federal funding helped fill some of the gap, but across the country money dedicated to sexually transmitted diseases has remained stagnant, with purchasing power decreasing by 40%. The year that Fresno County reported skyrocketing rates of congenital syphilis, state spending on infectious disease reached its lowest point in a decade. COVID-19 led to an explosive infusion of emergency funds, but public health money is typically siloed and can only be used for specific purposes.

“I don’t think we’re going to see the true picture of what we’re dealing with until COVID is put to rest,” Adams said.

In many instances, recession-era budget cuts equated to staffing cuts, reduced hours and clinic closures. In 2017, a survey by the National Association of County and City Health Officials showed 43% of local health agencies cut staffing and one-third reduced or eliminated services for sexually transmitted infection programs nationwide.

No agency or organization tracks STD clinic closures in California, but anecdotally, health officials know it has happened. Fresno closed its full service clinic in 2010. Kings County closed its HIV clinic later the same year. Sonoma County closed its HIV clinic in 2009.

More recently, the COVID-19 pandemic and monkeypox outbreak have only served to further stymie the state’s public health workforce. Sexually transmitted infection investigators in particular were extremely valuable during the early days of the pandemic due to their experience with contact tracing.

“The majority of the team was pulled to do contact tracing for COVID-19. Nurses were pulled to do testing and vaccinations,” Vang said.

The waiting room in the Fresno County Department of Public Health on June 8, 2022. Photo by Larry Valenzuela, CalMatters/CatchLight Local

All nine of Fresno’s sexually transmitted infection investigators were assigned to COVID-19 response. Vang and one other investigator were given every other day to respond to high-priority syphilis and HIV cases. Between the two of them they struggled, with their caseloads ballooning from a manageable 25 to an overwhelming 70 each. For a full year the department couldn’t offer treatment.

The same holds true at the state level in the health department’s Sexually Transmitted Diseases Control Branch, which works to reduce the transmission of sexually transmitted infections. The branch hasn’t released detailed infection data or reports since 2019 because half of the branch’s staff were redirected to COVID-19 emergency response. Now, monkeypox has further strained staff time and resources.

“Some staff remain redirected to the COVID-19 response more than two and a half years later, and the program is still working to backfill these positions,” spokesperson Ronald Owens said in a statement. “In addition, many other STD Control Branch staff are now currently redirected to monkeypox response.”

What is the state doing now?

If she had all of the money in the world, Adams, the Fresno STD program director, said she would hire public health field nurses to work in tandem with her disease investigators and social services case workers.

The program had a taste of that in 2016 when the state sent extra resources its way. Nurses were able to provide syphilis treatments on-the-spot, a critical strategy since the three-shot treatment many patients need must be given exactly seven to eight days apart and many patients miss follow-up appointments. If they miss a treatment, they have to start the antibiotic course from the beginning.

“For a lot of clients it may be your one and only chance to help them when you have them,” Adams said.

Case workers could also help patients find substance abuse treatment programs and with housing needs. By 2018, the combined forces of state, local and even federal resources helped turn the outbreak around, but the funds dried up — and then the pandemic hit.

Nurse prepares blood draw at the Fresno County Department of Public Health on June 9, 2022. Photo by Larry Valenzuela, CalMatters/CatchLight Local

They lost their dedicated nurse. The case worker transferred to another department. A dual investigator and phlebotomist, who could do blood draws for testing, retired. Investigators were pulled for COVID-19 work. Now, they share resources with the tuberculosis and immunization teams, which limits their flexibility.

“They do have their own patients, so I try to make things as quick as possible for them,” Vang said in June. “This week we’ve only treated one person. Pre-COVID we had two to three patients every day coming for treatment.”

The most recent state budget included $30 million to combat syphilis and congenital syphilis. That number is $19 million less than what legislators originally proposed, but still represents the largest investment in combatting sexually transmitted infections in state history. Gov. Gavin Newsom and state legislators also approved $300 million annually for public health, filling some of the hole created during the Great Recession.

In a statement, Owens said the state health department will use the additional funding to work with local health departments. The money will likely be used to bolster existing programs and address racial disparities seen among babies with syphilis, Owens said.

The state health department declined to make anyone available for an interview.

Craig Pulsipher, associate director of government affairs for AIDS Project Los Angeles Health and a member of End the Epidemics, which pushed for the money, said the targeted funding will help offset the thinning of resources that inevitably happens when money is divvied up amongst the state’s 58 counties.

“The counties that account for the largest number of cases are often left with inadequate resources commensurate with the epidemic in those counties,” Pulsipher said.

There are other bright spots on the horizon, too. Last year, Newsom signed into law a measure making California the first state to require insurance plans to cover at-home tests for sexually transmitted infections. Proponents of the measure say it’s an important step toward eliminating testing barriers and bringing some services back to rural areas.

Still, considering the decade of underfunding coupled with population growth and more severe community needs, the latest infusion of money is only the start of what experts say is needed to stop the spread.

“Look at the resources put together for COVID compared to resources for STDs in general. It pales in comparison,” Dr. Mhaissen in Madera said. “These resources are lacking completely in public health and that directly contributed to its reemergence.”

California spent roughly $12.3 billion between 2020 and 2021 to combat COVID-19 in addition to $110 billion from the federal government, vastly outstripping the amount spent on infectious disease prevention prior to the pandemic: roughly $83 million.

The lack of public health resources pushed many of the testing and treatment responsibilities onto the primary care system, but most doctors aren’t equipped to interpret the complex test results, which differ based on a patient’s history of prior infection. Many primary care practices also don’t offer treatment because it costs them thousands of dollars per dose to keep in stock.

“The test results are very confusing. I get confused,” said Mhaissen, who specializes in pediatric infectious disease.

He fields calls from across the state every day from obstetricians and pediatricians asking how to interpret results and what the best course of treatment is for mother and baby. Public health STD investigators like Vang are trained for this work, but as funding has dwindled so has their capacity.

“One hospital can’t fix this. One provider can’t fix this,” Mhaissen said.

Back in Fresno, Adams said she’ll be satisfied her team’s work has been effective once syphilis case rates are low enough for her investigators to work on other infections.

“It would give me the opportunity to shift priorities and we could begin to focus on another STD like gonorrhea or chlamydia,” Adams said.