Coping with Academic Pressure: Navigating Stress and Success in Chinese Families

The story was co-published with World Journal as part of the 2024 Ethnic Media Collaborative, Healing California.

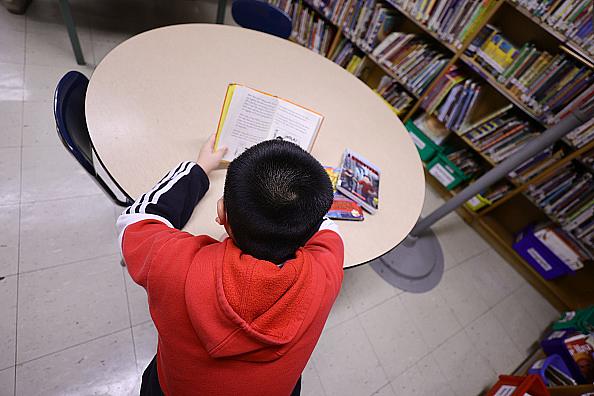

Photo by Michael Loccisano/Getty Image

Most parents raise their children in what they believe is the best possible way, hoping to provide them with a better upbringing than the one they had. Yet, oftentimes, parents’ earnest efforts to create a better environment can have a negative impact on the children.

Immigrant Chinese parents often follow a familiar pattern of parenting characterized by high academic expectations, the pursuit of prestigious schools, and authoritarian practices. Inspired by their own experiences, Chinese parents embrace traditional values and invest significant time, money, and energy in their children’s education, despite debates and disapproval surrounding such approaches. Consequently, children raised in such families often deal with psychological or emotional issues on their own.

USC clinical psychologist Jiayu Zhao, providing counseling for families in Glendale explained that the relentless pursuit of academic success can have detrimental effects on the mental and emotional well-being of children and youth. Some may experience stress, anxiety, and burnout as they attempt to meet expectations and cope with intense academic competition, which can also contribute to feelings of inadequacy, low self-esteem, and depression.

“In such a growth environment, children form an unhealthy self-judgment standard - entirely based on academic performance. When one's confidence is solely derived from their own achievements, such as whether they can achieve a certain score, gain admission to a particular school, or meet parental expectations, or compare with peers, then their self-esteem and confidence are not entirely genuine. Once their performance is less than satisfactory, their confidence will plummet."

Furthermore, too much focus on academic achievement and being constantly in a state of competition may come at the expense of other important aspects of development, such as social skills, creativity, and emotional intelligence.

Some parents like to compare their children to other high-achieving children. This puts undue pressure on the child. Even if a child's academic performance is excellent, they may still worry about not being outstanding enough, which is hard to shake off.

Twenty-one-year-old Leo Li from Northern California recalls a serious conversation initiated by his mother during junior high: "That day, she laid out a very clear future plan for me: a list of schools from high school to college, extracurricular activities, university majors, professional choices… She even set standards for monthly salary after graduation."

"What if I couldn’t pass the exam?" Li blurted out. Instead of directly answering, his mother presented the harsh reality to the little Li with numbers and calculations: monthly rent, utilities, food expenses, etc. She then asked, "If you can't earn this much money, how will you live?"

"At that moment, only one idea came to my mind: if I can’t pass the exam, I'm finished."

Parents Care About "Saving Face"

According to a 2023 Pew Research study investigating parenthood across different ethnicities, when looking ahead to when their children are adults, Asian parents are the most likely to say it is extremely or very important to them that their children earn a college degree. However, too much focus on academic performance often distances parents from their children.

"Some children think that their parents' love is conditional, only given when they excel." In her clinical experience, Zhao believes that Chinese parents sometimes overly emphasize outcomes, focusing entirely on scores, while neglecting the effort put forth by their children during the learning process. Some children may have already tried their best but are unable to meet their parents' expected scores. On the other hand, some children may struggle in certain subjects, leading to a less-than-ideal academic performance.

Shyan Chao, the Youth Prevention Coordinator at Pacific Clinics-Multicultural Family in the San Gabriel Valley, frequently hears complaints from teenagers that parents care more about their children's good grades than about them because good grades can give parents "face," or standing in the community, and an opportunity to boast to other parents about their parenting abilities .

A fourth-grade Chinese child once told Chao, "Studying hard leads to good grades, good grades get you into good colleges, good colleges lead to good jobs, and good jobs give me a prosperous life." Although Chao often hears this in the Chinese community, it was surprising coming from such a young child. The child mentioned that it was what his parents told him. At that time, the child's parents were applying for psychological counseling for their child, who was showing signs of anxiety.

The excessive focus of Chinese parents on academics makes some children evade their parents or refuse to share more about school activities, said Chao. As a result, parents complain that their children are impatient when talking to them and lock themselves in their rooms playing video games as soon as they get home," she said.

Under academic pressure, Li, in his teens, experienced a long period of depression, unable to understand or alleviate his negative emotions. He sought help from outside sources and became a member of a National Alliance on Mental Illness peer group. "When faced with academic pressure, children react differently. Some children can transfer their emotions through friends or other channels, while others become depressed or irritable." he said.

“Look At How Hard We Work"

Li adds that parents today rarely explicitly demand that their children achieve a specific score on important exams, but they subtly impose academic pressure on their children through words or actions. For example, they relate the hardships of their own work and life, or often mention the word "sacrifice."

In the peer group of children from Chinese immigrant families, Li often hears students saying they feel "a lot of pressure, very tired," or blaming themselves for not achieving good grades and feeling guilty and shamed in front of their parents.

Wendy Guo, a social worker from MHACC, came from a Chinese immigrant family and said she experienced parental violence during her childhood. She recalled that they resorted to shaming and guilt-tripping tactics, but rarely offered positive encouragement. “Look at how hard we work, you should study well," they often told her, but ironically, were never directly involved in her academic progress.

“It seemed as if they avoided as much responsibility as they could, and placed their hope of moving up the socioeconomic ladder on their child as opposed to working towards it themselves.” Guo said. She understands that they might have felt helpless in their inability to transcend the socioeconomic barriers immigrants face. However, she also felt that there was a lack of desire for self-improvement and knowledge because they never put in the effort to learn English despite being in the U.S for many years.

Zhao mentioned that some parents do have serious issues with confidence, needing to highlight their own value through their children's performance.

Differences in Expectations Between Parents and Children

Chao says that although every family has different immigration backgrounds and stories, most of the Chinese parents she encounters immigrated to the United States to provide their children with a better education and future. Parents' expectations for their children are centered on good grades. When children fail to meet these expectations, parents' disappointment is inadvertently conveyed in their words, causing children to feel worthless. “Of course, this is not the parents' intention, but different expectations for the future,” Chao said. Children exposed to American education and culture often ask her, “Did immigrants come to the United States for a different way of life?"

Zhao said, when children feel hopeless and believe that no matter how hard they try, they cannot meet their parents' expectations, they may look for ways to escape the pressure, such as overeating, self-harm, alcohol abuse, or even suicidal thoughts.

What Do Parents Think?

Some Chinese parents believe that a liberal upbringing will make children retreat when faced with difficulties, so they feel the need to propel their children toward academic rigor. A phrase Chinese parents often say, according to Chan, is, "Although they (the children) don't understand now, they will know in the future that I am doing this for their good.”

An ethnographic research focused on two Chinese immigrant families over a five-year period, in the early 2000s revealed that parents and children in Chinese immigrant families often acculturate at a different pace and have different expectations, which in turn often create conflict, feelings of distance, or even alienation.

From the parent’s perspective, authoritarian parenting is strongly associated with the desires and challenges of Chinese immigrant families in Western host societies. Such parenting practices are deemed necessary and appropriate because of the desire for success, the fear of generational decline, an identity or cultural crisis in others’ society, and globalized competition.

Zhao pointed out that emphasizing education is not only a cultural heritage of thousands of years; for immigrants, receiving higher education and excelling academically means having more opportunities in the future. From a survival perspective, education is an important pathway to success in a new country.

Jiayu Zhao’s counseling room in Glendale, decorated with Chinese-style ornaments.

Courtesy Jiayu Zhao

Communication: The Bridge to Connecting Differences

Based on Li 's experience in peer groups with children from Chinese immigrant families, when children feel they cannot meet their parents' expectations, they often react very passively: giving up on their academics, refusing social and recreational activities, and even contemplating extreme measures, such as self-harm and suicide. However, from the parents' perspective, it seems as though their children's academic performance and personalities have suddenly deteriorated.

The difference itself is not the issue; rather, it's the way these differences are handled that becomes problematic. Communication is the key to bridging the difference. Chao points out that many parents believe they understand the importance of communication and frequently engage in discussions with their children. However, according to feedback from the children, the communication from their parents often feels more like indirect "notifications."

"However, 'parent-child relationships are mutual; it's not just an issue on the parents' side,' Zhao pointed out. Sometimes it might be the child's problem, as they jump to conclusions, believing their parents are unreasonable and incapable of empathizing with their inner pain, without giving their parents a chance to change the parent-child interaction pattern. Some parents may not even be aware of the problem."

Seeking A Trusted Sharing Environment

According to Li, although schools provide psychological counseling support, many children don’t fully trust the school's counseling programs. This is because if issues, such as suicidal thoughts or behavioral problems, are identified by school counselors or mentors, their parents or teachers would be informed, which makes students feel trapped, unable to escape the supervision of school and parents.

At such times, the existence of peer groups becomes a safe outlet, providing children with a trustworthy emotional support environment. Furthermore, social workers in peer groups, having received professional training, can help other children release stress and negative emotions through their own experiences and from a peer perspective. In extreme cases, they also know how to seek legal or other forms of help and protection.

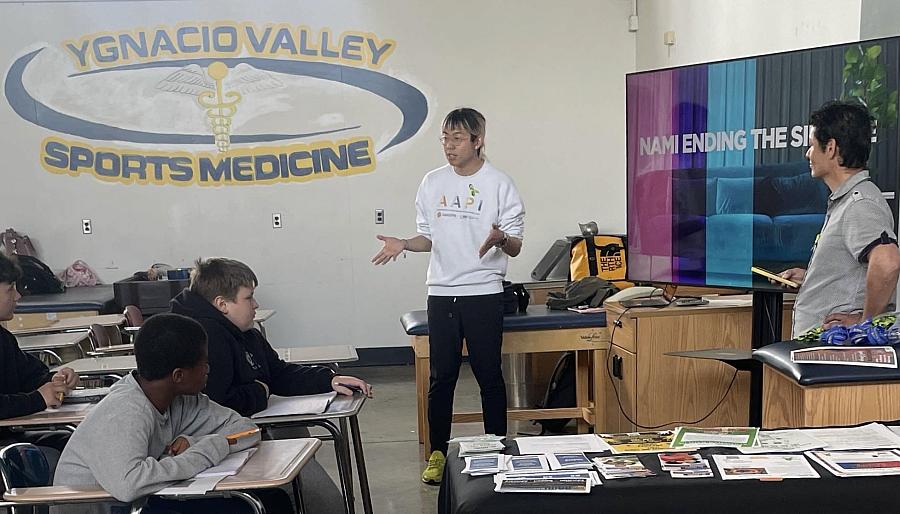

Leo Li shares his experiences at an event hosted by NAMI in April in Antioch, CA

Courtesy Leo Li

"In the end, what children need most is a trustworthy and relaxing environment or person to confide their stress and distress... This form can be a peer group, a student organization, or just three to five friends." Li says. Apart from their weekly online chats, Li and group members often arrange to go hiking or organize offline activities, which expands their interactions beyond just peer support times; they also become friends in private. "This continuous trust relationship is very important for children - they can receive immediate responses whenever they need help."

Guo stated that she only understood what a normal family looked like after leaving her family and entering college. During her childhood, she vented her fear and confusion through self-harm behaviors. Fortunately, she eventually found a way out and became a social worker at Mental Health Association for Chinese Communities, a nonprofit organization with a presence in the San Francisco Bay Area that provides mental support for Chinese families.

Wendy Guo from Mental Health Association for Chinese Communities at an outreach event in Pasadena.

Courtesy Wendy Guo

Peer groups, however, also have uncertainties. Zhao said that it was possible that children venting about their parents' behavior and family pressures to each other may create connections and provide some stress-relief effects, but group members may not necessarily have the ability to provide methods for dealing with challenges or improving resilience. They may even learn unhealthy coping mechanisms.

"Children can cultivate correct concepts through psychological counseling. On the one hand, they can recognize the problems associated with results-oriented thinking. On the other hand, they can enhance their resilience, communication skills, and ability to seek help."

Trending Towards A Balanced Approach

Recent studies have found that Asian parents are moving away from traditional parenting, particularly in Asia. A long-term study of Chinese parents indicates the recent prevalence of the "happy childhood" concept. A systematic study on school choices in Hong Kong suggests that parents have taken a more balanced approach to parenting, considering the importance of children's happiness alongside academic performance.

Zhao believes that more and more Chinese parents are becoming open-minded. Moreover, due to the vigorous promotion of mental health information in recent years, children are becoming more aware of their psychological states. Some children even actively seek psychological counseling. The stigma attached to mental health issues among Chinese parents has also improved.

Yifei Hu, a seven-month pregnant Chinese immigrant working as a lawyer in San Gabriel Valley, is about to embark on her journey of parenthood in July. Like her Chinese parents, Hu acknowledges the importance of education in shaping one's thinking and future development. She said she would provide her daughter with as many good educational resources and growth environments as possible. She does not have specific plans for her daughter’s future, "I hope she will be someone with her own thoughts and pursuits, not someone like me."

Instead, Hu values building a close mother-daughter relationship more than her expectations for her daughter's future success.

"Success is exhausting," said Hu's husband, Owen, who came to California with his parents during middle school. He believes that the most important aspect of education is to cultivate healthy values and personal abilities in children, which is far more important than academic achievements.

Yifei Hu and her husband Owen, photographed in Pasadena.

Courtesy Yifei Hu

However, Owen admits that a person's educational views are also closely related to the social environment they are in. When age is no longer a barrier to changing jobs or starting a business, and a person can still become anyone they want to be through their own efforts at the age of forty, parents are no longer obsessed with ensuring their children succeed from the starting line.

Li said, if he were to become a parent in the future, he would prioritize ensuring the safety and physical well-being of his children. He emphasized the importance of leading by example and imparting values through actions and words in their upbringing. While he might adopt a more open approach to minor issues, he would encourage his children to start making their own decisions and forming opinions around the age of 13 or 14, with his support and trust behind them.

Resources to Seek Help

Guo’s younger brother, who is over ten years younger than her, has gained some help and comfort through social media. Guo said although her brother also has mental problems, he has learned lots of psychological information and received mutual assistance virtually at a very early age. Compared to herself, her brother has better emotional management skills and is more capable of facing and addressing his own issues.

The 988 Suicide & Crisis Lifeline is a national network of local crisis centers that provides free and confidential emotional support to people in suicidal crisis or emotional distress 24 hours a day, 7 days a week.

Other Helpful Resources:National Eating Disorder Association 1-800-931-2237;National Runaway Safeline www.1800runaway.org ;The Trevor Project www.thetrevorproject.org

FostrSpace - an app for foster youth by foster youth www.fostrspace.com

Hope and help for families of alcoholics www.al-anon.org

Sexual Health: CDC www.cdc.gov/sexualhealth

Mental Health America www.mhanational.org/crisisresources

Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) www.samhsa.gov/find-help/national-helpline

National Domestic Violence Helpine www.thehotline.org