COVID Stole a Parent from Over 200,000 Children. Indian Country Lost the Most

The story was originally published by the MindSite News with support from our 2024 National Fellowship.

COVID was not an equal-opportunity destroyer. American Indian and Alaska Native children were orphaned at three times the rate of white children, and Black children at double the rate. Without support, children who lose a parent or caregiver are at risk of developing lasting problems with depression, lower academic achievement, and behavioral issues.

As the world reaches the 5-year COVID anniversary, grieving children still need support

Five years ago this week, the World Health Organization declared COVID-19 a global pandemic. The virus went on to kill 1.2 million Americans, the most of any country in the world. Many of those who died were parents, and the story of the children they left behind has gotten far too little attention. In Part 3 of our Forgotten Children series, we look deeper and focus in on Native American children, who lost parents at the highest rate of any group.

COVID-19 hit the Navajo Nation in waves, like an invisible tsunami that swept people away from their loved ones. Hospitals across the country overflowed with patients, but the virus had a particular ferocity when it hit remote Navajo communities in northern Arizona, New Mexico and Utah. In its wake, families were shattered: 2,000 Indigenous children in that region lost a parent or caregiver, according to one analysis. Yet that number doesn’t convey the grief that continues to reverberate at the five-year COVID anniversary.

For Chenae Yazzie, the sudden death of her father was hard to comprehend. It’s still something she avoids talking about. First her mother became ill – so sick that she could barely muster the energy to walk from the bedroom to the living room – but after about 10 days of sequestering herself, she got past the worst of it. Chenae was just 12 and attending school remotely in January 2021 when her father, Irvin Yazzie, began feeling sick. He suspected it was COVID, but he put off seeking help until his symptoms worsened. When he called an ambulance to come to the home where he was living alone, it was too late – even to say goodbye to his family.

Cheryl Nez with her daughter, Chenae Yazzie, 16, in their apartment in Winslow, Arizona.

Photo:Michele Cohen Marill

“It just happened so fast,” said Cheryl Nez, Chenae’s mother and Yazzie’s partner, who lives in Winslow, Arizona, just outside the Navajo reservation. “There was pretty much no contact of any sort – nothing.” He was airlifted to a hospital in Phoenix, about 200 miles away, where he was ensconced in a COVID ward and placed on a ventilator. No one was allowed to visit. Like so many of the more than 1 million Americans who died of COVID during the peak years of the pandemic, he died alone. He was buried without a ceremony, due to COVID protocols. Even the rituals of grieving were disrupted. Just like that, Chenae’s father was gone.

COVID left behind hundreds of thousands of children like Chenae: Although the virus was most deadly for older adults, an estimated 180,043 people in the prime parenting ages of 25 to 54 died from March 2020 to September 2023.

Leading cause of parental death

When deaths from COVID spiked in 2020 and 2021, there was no way to identify and track the orphans left behind – the children who lost at least one parent or primary caregiver. Researchers have since estimated the toll: 216,617 U.S. children had a parent or caregiver who died from COVID through approximately the first two years of the pandemic, according to a 2022 analysis. Half of them were between the ages of 5 and 13.

A 2025 report in Nature Medicine examined orphanhood in 2021, the year Irvin Yazzie died, and estimated 494,036 children lost a parent or grandparent caregiver from all causes. COVID was the leading cause of parental deaths for every racial and ethnic group except among the non-Hispanic white population, which had more deaths from drug overdose.

The pain was felt acutely in communities of color: American Indian and Alaska Native children were orphaned at a rate three times greater than white children, and Black children had double the rate of loss. In fact, teenagers who are American Indian or Alaska Native lost parents at rates comparable to children in the African countries worst hit by AIDs, said Susan Hillis, a researcher at Imperial College London.

“We should not be sleeping at night because of that,” said Hillis. “Who is doing anything to help them?” She co-chairs the Global Reference Group on Children Affected by Crisis, a network of experts who study the impact of COVID and other crises on child well-being. The World Health Organization, U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID), and U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention were among the sponsors.

At COVID anniversary, indigenous youth still struggling

Without support, such as grief counseling or peer-based groups for children and parenting skills training for caregivers, children who lose a parent or caregiver are at risk of developing lasting problems with depression, lower academic achievement, and behavioral issues. Yet vulnerable communities have barriers to getting those supportive resources.

I had to stand up for my kids and just be as strong as I could.

Cheryl Nez

Like many rural areas around the country, the Health Resources & Services Administration designates the Navajo Nation as a “high-needs mental health provider shortage area.” For example, Navajo County, Arizona, a rectangular swath that encompasses parts of the Navajo, Hopi and Apache reservations as well as the town of Winslow, has just one mental health provider for every 980 people. That is about half the ratio of mental health providers in Arizona as a whole (one for every 550 people), and one-third of the U.S. rate (one per 320).

For Chenae and Cheryl, Irvin Yazzie’s death came just months after another tragedy: the death of the man who was the father of her two sons – Chenae’s half-brothers – due to injuries in a horse-training accident. “That year was the hardest,” said Nez. Although many Navajo avoid discussing death, she knew she needed to help her children cope and reassured them that she is always available to talk. “I had to stand up for my kids and just be as strong as I could. To this day, it’s still hard for them.”

Like many rural areas around the country, the Health Resources & Services Administration designates the Navajo Nation as a “high-needs mental health provider shortage area.” For example, Navajo County, Arizona, a rectangular swath that encompasses parts of the Navajo, Hopi and Apache reservations as well as the town of Winslow, has just one mental health provider for every 980 people. That is about half the ratio of mental health providers in Arizona as a whole (one for every 550 people), and one-third of the U.S. rate (one per 320).

For Chenae and Cheryl, Irvin Yazzie’s death came just months after another tragedy: the death of the man who was the father of her two sons – Chenae’s half-brothers – due to injuries in a horse-training accident. “That year was the hardest,” said Nez. Although many Navajo avoid discussing death, she knew she needed to help her children cope and reassured them that she is always available to talk. “I had to stand up for my kids and just be as strong as I could. To this day, it’s still hard for them.”

Comfort from clan connections

Chenae was a student at Winslow Junior High School during the pandemic, and that timing turned out to be fortuitous. Lavinia Cody had recently begun working as a school counselor for the Winslow Unified School District, providing counseling services for kindergarten through eighth grade at four schools. About half the students at the junior high school are American Indian – mostly Navajo – and Cody noticed how frequently children were taking days off due to deaths in their family. She understood their grief acutely; her mother and grandmother died of COVID weeks apart in November 2020.

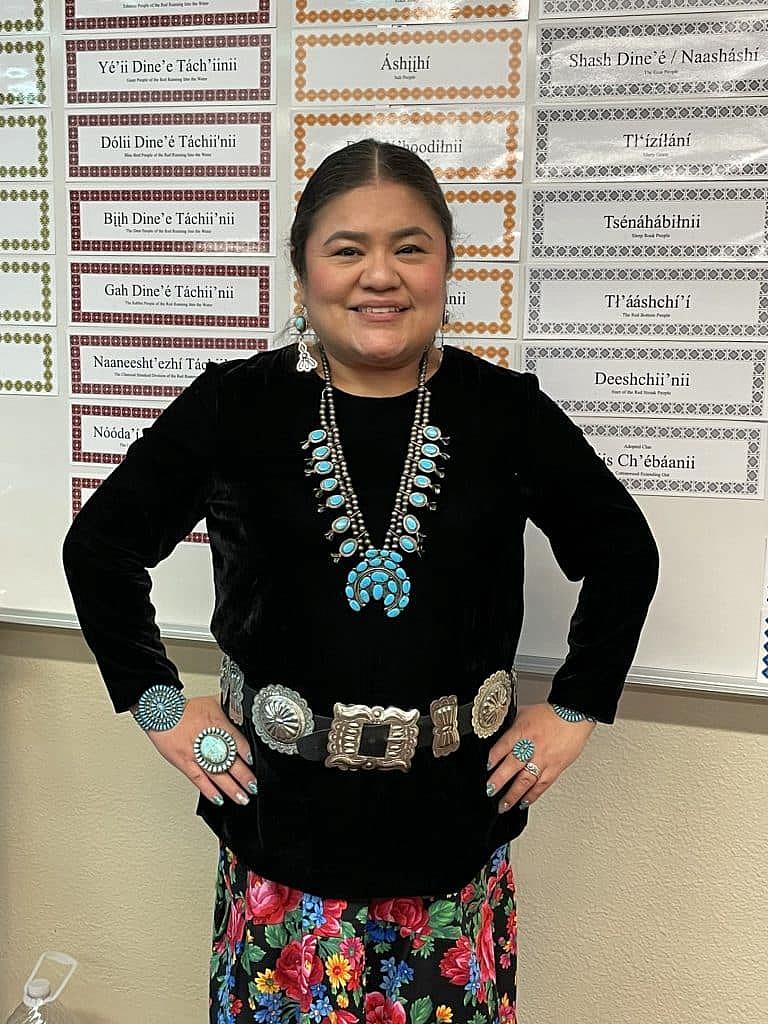

School counselor Lavinia Cody lost her mother and grandmother to COVID. Her experience fueled her determination to create healing opportunities for students by teaching them about their connection to other clans in the Navajo (Diné) Nation.

Photo: Michele Cohen Marill

Cody was able to secure a small grant through a professional development program at Northern Arizona University in Flagstaff to create a grief support curriculum based on Navajo traditions. Cheryl Nez saw the posters in Cody’s office displaying Navajo language and culture, and she wanted Chenae to be a part of the program.

In that inaugural grief group, the children sat in a circle, sinking deeply into brightly colored bean bag chairs, as Cody explained the stages of grief: denial, anger, bargaining, depression and acceptance. Cody gave each child a loose-leaf binder for a journal and asked them to describe their own grief feelings. “I would say that I’m in between bargaining and depression because I would sometimes feel like I wanna change whatever happened,” Chenae wrote. “Then I go back to feeling like hopelessness and I wanna isolate myself. So I just go back and forth.”

I felt alone. But when I would go places, people were calling me ‘shi yazhi’ (little one), ‘shi awé’ (my baby), embracing me, hugging me.”

lavinia Cody, school counselor

Cody began to talk to the children about Ké – the relationship of clans among the Navajo (Diné) people. Each baby is born into four clans – two from each parent, although the matrilineal clans are the dominant ones. As she crafted her curriculum, Cody thought about her own experience after losing the matriarchs of her family.

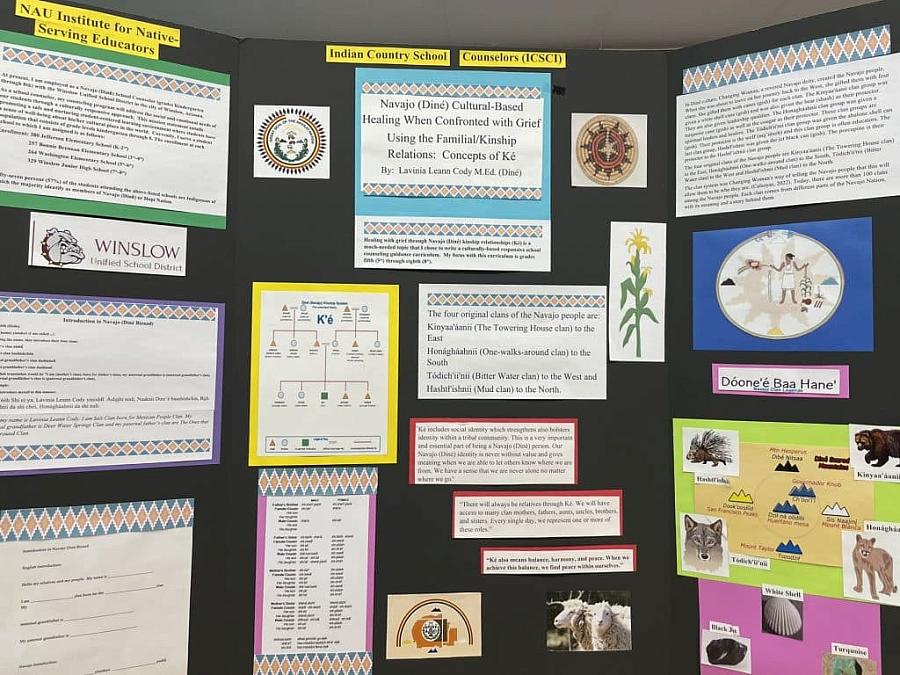

A poster describing Lavinia Cody’s approach to using kinship relationships as a way to address children’s grief was presented at the Indian Country School Counseling Institute Showcase at Northern Arizona University in 2022.

Photo: Michele Cohen Marill

“I felt alone,” she said “But when I would go places, people were calling me ‘shi yazhi’ (little one), ‘shi awé’ (my baby), embracing me, hugging me.”

She felt comforted by an extended family with deep ties – even if they were people she barely knew. She wanted to share that feeling with her students. “You’re not alone,” she told them. “You have many relatives everywhere. You’re going to run into someone that is going to be related to you.”

In fact, Chenae and Cody are both connected to the Salt clan, one of the Navajo Nation’s 100-plus clans – Chenae through her father and Cody through her mother. Cody began referring to Chenae as “shi yazhi,” a term of endearment. Other students had similar clan connections. “I’m not only their school counselor – I could be their aunt or cousin,” Cody says. “It builds ties on a different, deeper level.”

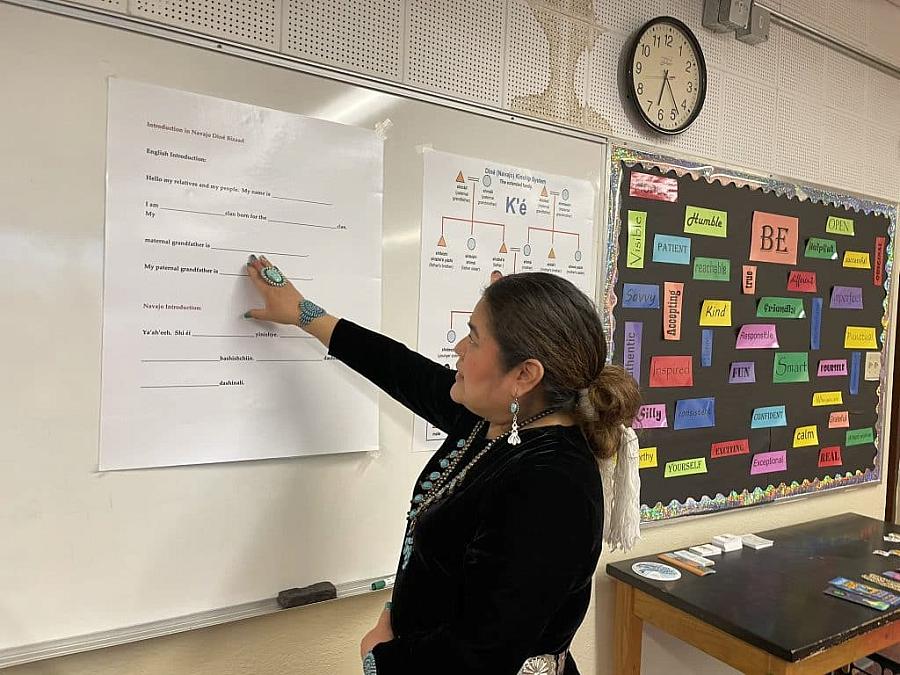

Lavinia Cody has her students use a form to trace their connections to members of other clans.

Photo: Michele Cohen Marill

Cody’s approach is based on tradition, but it is also backed by research. From August 2021 to May 2022, Emily Haroz, associate professor of public

health, and her colleagues at the Johns Hopkins Center for Indigenous Health surveyed parents and other primary caregivers of students at schools that serve the Navajo Nation. They found high rates of depression and anxiety among the parents and caregivers:

15.7% of children were at risk of mental distress, based on parent and caregiver reports. Yet the survey also showed that strong connections to culture gave the children higher levels of resilience and academic “self-efficacy.”

“Part of mental healing is relational, particularly in (Indigenous) communities,” Haroz told MindSite News. Haroz and other Johns Hopkins researchers are now studying whether community mental health workers could be trained to provide coping strategies, peer support, home visits, and other services in tribal communities – a model of extending behavioral health care that has been used in low-resource areas globally.

“Training people from the community, who understand the local context and culture, is a potential real solution to some of these barriers to accessing services,” Haroz said.

‘Woefully inadequate’ investments in children

Nationwide, COVID’s death toll galvanized advocates for newly bereaved children. “Children: The Hidden Pandemic 2021,” a report from an expert working group now known as the Global Reference Group for Children Affected by Crisis, warned that COVID orphans could suffer “devastating and long-term impact on their economic, physical and emotional welfare” similar to the impact felt by the global orphans of HIV/AIDS.

Prominent U.S. public health figures and political leaders formed the COVID Collaborative “to defeat COVID-19” by preventing the spread of the virus and improving access to life-saving vaccines and treatments – and they also joined the call to support bereaved children. In December 2021, the Collaborative released “Hidden Pain,” a report that urged Americans to “stand beside these hidden victims during the toughest days of their lives and beyond.”

It identified strategies including public funding to increase grief-focused programming, a federally-funded mentoring program for COVID-bereaved children and creation of a national Children’s Fund to provide one-time support payments and financial assistance to help bereaved families access mental health services. Those recommendations went unheeded. While COVID relief funds did fund additional mental health services, particularly in schools, no national strategy emerged to address COVID-era orphans.

‘Children and hidden and suffering’

“What the world shares in common is that children are hidden and suffering, and the investments for them are woefully inadequate,” commented Hillis.

It isn’t always that way. The 9/11 terror attack provoked an immediate outpouring to help orphans. Charities such as Tuesday’s Children and the Twin Towers Orphan Fund gave educational assistance and mental health services to children who lost a parent in the tragedy. To forestall lawsuits, Congress created a federally funded September 11 Victim Compensation Fund, which provided payments to families of people who died as well as compensation to thousands of people with injuries or health effects from the attack or its cleanup. Through 2024, it had paid out $14.9 billion. Additionally, a $4 million federal grant boosted mental health services in New York City schools.

COVID was a very different trauma – one felt across the globe – and in the U.S., parental deaths were about 70 times greater than those from 9/11. Yet for COVID orphans, support has been far more limited – and mostly dependent on philanthropy rather than public funds. The broad range of federal pandemic relief programs – cash payments, student loan deferments, rental assistance – didn’t directly address COVID orphanhood. A 2021 U.S. House bill to create a COVID-19 Victims Compensation Fund did not even get a committee hearing.

New York Life Foundation, the largest private funder of child grief programs, has supported a network of “grief-sensitive” schools around the country and bolstered organizations that work with bereaved children and families. As the pandemic unfolded in 2020, the New York Life and Cigna foundations created the Brave of Heart Fund to finance grief support programs and provide assistance to families of health care workers who died from COVID. “Our experience has been not just in providing funding, but in really working hand in hand with these organizations to identify where the gaps are and to strengthen the field as a whole,” said Heather Nesle, president of New York Life Foundation.

In 2022, California established a $100 million trust fund – the HOPE program – for children who lost a parent or primary caregiver to COVID, the first state to do so. Children who were eligible for Medi-Cal, California’s Medicaid program, when their parent or caregiver died of COVID or who have been in foster care for longer than 18 months, are eligible to receive accounts of $4,500, along with financial education and guidance, when they turn 18.

At the 5-year COVID anniversary, children still vulnerable

The program, run through the state’s treasury department, is due to launch in January 2026. Director Kasey O’Connor estimates that 10,000 children qualify – about a third of all California children who lost a parent or caregiver to the disease – and her staff is relying on community partners and school districts in low-income areas to help identify them. The trust accounts, while small, are intended to give a boost to children whose parent or caregiver had no assets to leave behind, a step toward bridging the generational “wealth gap,” O’Connor said.

These children are hidden, and we’re working to ensure they’re out there in the light.

Kristin Urquiza, executive director, marked by covid

Kristin Urquiza, whose father died of COVID in June 2020, is founder and executive director of Marked By Covid, a “justice and remembrance movement led by Covid grievers.” A member of the HOPE advisory board, she has been advocating for financial assistance for COVID orphans, many of whom are the children of essential workers who helped keep the country running when most businesses and services shut down.

Helping them hasn’t been easy. The COVID pandemic became politicized in ways far different from other major disasters. At the five-year COVID anniversary, pandemic orphans and their families are quietly struggling to get by without the income of a breadwinner.

“Right now, these children are hidden, and we’re working to ensure they’re out there in the light,” said Urquiza. “These children are some of the most vulnerable kids out there to begin with, and now they’re even more vulnerable because they lost a parent.”

New York City was an early epicenter of the pandemic, and as of late February, 46,825 city dwellers had died of COVID. Urquiza remains optimistic that the state will provide “baby bond” funds to support COVID-bereaved children. A 2023 bill to create a New York COVID-19 Children’s Fund would have added $1,000 every year to savings accounts until a COVID orphan turns 18, money that could be used toward higher education, buying a home or starting a business. Yet despite an initial media blitz, it never received a hearing. The bill was reintroduced in the state Assembly in January 2025. Urquiza is hoping to bring surviving children and their caregivers to meet New York Gov. Kathy Hochul, but says she has not yet been granted an appointment.

‘An unseen deadly enemy’

When COVID came to the Navajo Nation – where it was called Dikos Ntsaaígíí, or big cough – it spread swiftly among a vulnerable population. “It was just unavoidable. It was everywhere,” said Thomas Walker Jr., a longtime delegate to the Navajo Nation Council who is now an advocate for tribal communities. “That was the reality – an unseen deadly enemy.”

The reservation encompasses 110 communities, or “chapters,” many of them remote. In 2020, more than 30% of the reservation had no running water; water was delivered to homes by truck. An influx of COVID relief funds helped many areas get water lines or electricity, but many gaps remain. Despite the vastness of the land, housing is limited and families often live in multi-generational households. More than 9,000 miles of rugged dirt roads make it hard to access health clinics or hospitals – which could be 50 miles away or further.

Historical trauma contributes to health risks, too. In 1864, the U.S. military destroyed Navajo homes and burned their food stocks, forcing them on a 400-mile trek that became known as “The Long Walk.” Thousands died of starvation, disease, injury and harsh conditions before eventually returning to a portion of their homeland. Meanwhile, the U.S. government sought to assimilate Indigenous Americans by forcibly removing children to boarding schools where they were not allowed to speak their native language. Tribal communities relied on the commodities from a federal food program that provided foods that were not a part of their normal diet, such as lard and cheese. Today, the Navajo have high rates of diabetes, heart disease, alcoholism, substance use disorder and other chronic conditions.

The first COVID cases appeared in mid-March of 2020 in the Navajo town of Kayenta, Arizona. As the virus spread, President Jonathan Nez announced an evening and weekend curfew, and schools and non-essential offices shut down. Navajo police set up road blocks to enforce the curfew, and Navajo leaders used that opportunity to educate drivers about COVID prevention. Mask-wearing was mandatory. The Navajo Epidemiology Center created a COVID-19 dashboard and closely tracked the spread.

As program director of the Navajo community health representative and outreach program, Mae-Gilene Begay supervised the workers who traveled throughout the 110 communities to connect people with health screening and resources. She became a leader of the Nation’s COVID-19 Health Command and joined her staff in personally calling patients for case-tracking and prevention efforts.

Some of those conversations still haunt her. “At the beginning, we thought it was going to get contained,” said Begay, who lost an aunt and uncle to the disease. “It just continued getting worse and worse.” In some households, the elders who died of COVID were primary caregivers who had been raising their grandchildren; social service workers sought other relatives or foster families to take in the children, Begay said.

Often, the children didn’t understand what was happening, she said. “They didn’t know what the sickness was and why it was taking their relatives away,” said Begay, who retired in September 2021. “Each day, I went home feeling their pain, feeling their loss.”

Traditional healing and resilience

The town of Tohatchi, New Mexico, lies in a valley of the Chuska Mountains, a small community barely visible from the divided four-lane highway that bisects it. Still, it is a central hub, with four schools, several churches, Navajo offices and a health clinic. Margie Silva’s hogan is down a dirt driveway across the street from the clinic, a modern version of the traditional eight-sided Navajo dwelling. It has drywall and vinyl siding instead of walls made of logs and mud, but inside the hogan has traditional features: a dirt floor and a conical wood-frame roof with an opening for the wood stove’s long exhaust pipe.

Margie Silva, a traditional healer and practitioner in the Native American Church of New Mexico, conducts ceremonies in her hogan, a traditional eight-sided structure with a pitched roof.

Photo: Michele Cohen Marill

Silva is a traditional healer and practitioner in the Native American Church of New Mexico, which blends traditional practices with Christianity. Through ceremonies and prayers, she helps people cope with their depression, grief and pain and regain their emotional and physical strength.

When she greets a visitor, Silva sits facing east. On the ground before her is a small woven mat with an eagle feather, a symbol of the sacred, high-soaring birds that fly the Navajo prayers to the heavens. Next to it is a pouch of tobacco, a pile of hot coals, a bucket of water, a small piece of corn husk and a chunk of cedar for lighting; sharing a smoke smooths the way to conversation.

An eagle feather rests on a mat at Margie Silva’s feet in her hogan in Tohatchi, New Mexico. Eagles, which soar higher than other birds, are sacred in Navajo (Diné) culture as a bridge between the physical and spiritual worlds.

Photo: Michele Cohen Marill

While the hogan is the spiritual place for Silva’s work, during COVID she traveled to homes and led prayers in open air, hoping to avoid exposure to the virus. “I was honored for these people to reach out to me to pray for them and really humbled that they have the faith in this medicine,” said Silva, who learned traditional practices from her parents.

Even people who had turned away from Navajo ways found their way back. One in four American Indians and Alaska Natives sought traditional healing to help manage COVID symptoms and one-third used traditional medicine or healing to cope with pandemic stress, according to a Native American COVID-19 Alliance Needs Assessment survey conducted across the country in early 2021. Indigenous healers like Silva recommended herbal remedies and performed sweat-lodge ceremonies to cleanse the body and spirit and ease COVID symptoms as an adjunct to Western medicine. When vaccines became available in 2021, the Navajo Nation had a massive vaccination campaign and led the country in getting its population protected.

As the pandemic subsided, Silva has continued to work with people who have lingering effects from COVID or who are still grappling with grief over the loss of loved ones. “In our own traditional way, we can intervene and help with their mental state by reintroducing them to the traditional way of thinking,” she said. “To me, that is a self-healing way.”

Trauma and tradition

At the five-year COVID anniversary, many in the Navajo Nation find that the magnitude of their pandemic experience – and of their loss – has been eclipsed by the need to address day-to-day challenges.

“It seems like once we got COVID under control, we just went back to normal, if you want to call it that – back to fast-paced society – and we didn’t debrief, have a discussion of healing so that the next generation doesn’t have trauma,” said Nez, the Navajo Nation’s former president. He now has a consulting firm that promotes nutrition and health among the Navajo and other Indigenous communities as a way to boost their ability to fight future infections.

Many Navajo elders died of COVID, taking with them their stories and teachings. Still, traditional practices have acquired an accepted role in behavioral health. Child psychologist Dolores Subia BigFoot has long been blending cultural context with evidence-based practices. In 2004 she founded the Indian Country Child Trauma Center at the University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center and developed culturally appropriate treatment protocols and training programs for clinicians who work with tribal communities. “Honoring Children, Mending the Circle” is her adaptation of trauma-focused cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT).

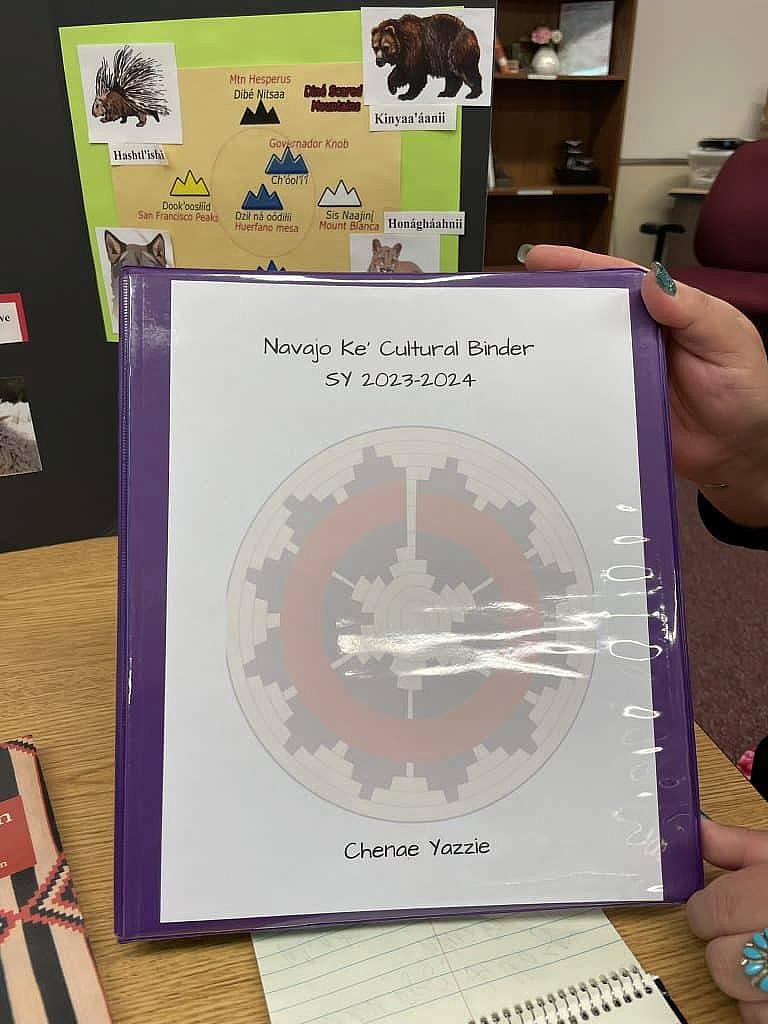

The binder Chenae Yazzie prepared with help from her school counselor, Lavinia Cody.

Photo: Michele Cohen Marill

“Our tribal communities that have incorporated as much culture as possible are the ones that are the strongest or the most resilient,” BigFoot said.

In her apartment in Winslow, Cheryl Nez displays items once used by Irvin Yazzie’s grandmother, such as a wooden weaving wand and a ceremonial hair brush. Posters that feature eagles and other iconic Navajo images flank a huge American flag; Nez’s father was a Vietnam veteran.

When Chenae turned 16, her brothers arranged for an all-night traditional ceremony marking the occasion. There was eating, singing and drumming, and prayers for Chenae’s well-being and health. The ceremony also helped Chenae and her family feel connected to her father, who taught her about Navajo beliefs and language.

Today, Chenae is coping well, but some days the loss of her father just hits her – that he’s never going to be there, that he won’t see her graduate from high school or reach other important moments. “People die in so many ways, but this COVID just kind of swept under our feet and took people away unexpectedly,” says her mother, Cheryl Nez. In that sadness, Nez hugs her daughter and cries with her. “Just being there for one another is all we can do.”