Nana kept her grandkids out of foster care. Then the foreclosure notice arrived

This article was published in USA Today with support our 2025 Child Welfare Impact Reporting Fund.

Rochelle feeds her granddaughter, Briana, in her home in San Antonio, Texas, on Aug. 24, 2025.

Lorianne Willett, For USA TODAY

SAN ANTONIO – Jayden leaned against Nana’s leg as she teased coconut conditioner through his wet curls with her fingers. The 2-year-old clapped his hands, looked up and said “bottle” in baby babble.

“Not yet, sweetie,” Rochelle told her grandson, giggling before she continued in a singsong voice. “Almost J.D. Not yet though.”

After the Texas Department of Family and Protective Services took them from their parents, this became part of the morning routine for Rochelle and her two grandbabies. In quiet moments like these, the nana focused on her grandkids instead of the challenges she faced.

State officials promised to help Rochelle, but that aid never arrived, came late, had strings attached or did not match the support given to strangers who take in foster children. As a result, Rochelle faced foreclosure on the brick suburban home in San Antonio that sheltered them. She came to fear caseworkers would remove the kids instead of helping her.

“The public only knows that the children need to be protected and believes the agency tasked with such protection would also protect the family and not cause additional harm by telling them one thing and doing another thing,” Rochelle wrote in a August email to a state caseworker.

She is among millions of Americans who are caring for young relatives, including some in state custody. Child welfare leaders declare victory when “kinship families” step up: Fewer children go into costly foster care and more kids stay with people they love. In truth, relatives say, child welfare agencies hand them the bill – and blame them when they can’t afford it.

“They put up barriers then say it wasn’t their fault,” Rochelle said.

In Texas, kids taken into state custody leave a kinship placement twice as often as the nationwide rate, according to a USA TODAY analysis of federal data tracking kids removed from their homes in a four-year period.

USA TODAY is using first names for Rochelle’s family to protect the privacy of children too young to consent to sharing sensitive private information. A reporter confirmed her story through dozens of interviews with the parents, extended family, friends and officials and by reviewing hundreds of pages of emails, text messages, contracts, court transcripts and other documents.

Texas law allows Department of Family and Protective Services and its division of Child Protective Services to keep its work with families secret.

“Because we believe strongly in respecting the rights of the children and families we serve, we do not release confidential details of interactions with CPS clients,” DFPS Spokeswoman Marissa Gonzales wrote in an email to USA TODAY. “After a thorough review, we can confirm DFPS has followed its policies in relation to the case.”

A letter from the kids’ pediatrician describes how Rochelle was active in their lives since birth despite navigating a career transition that had her commuting daily between San Antonio and Austin. Rochelle, in her 50s, is working toward a master’s degree and ordination at Austin Presbyterian Theological Seminary. She has worked part-time as an instructional aide on campus, as a beadle for the chapel, and as a guest speaker delivering sermons at area churches.

Rochelle, a master's degree student at Austin Presbyterian Theological Seminary, gives a sermon at First Presbyterian Church of New Braunfels, Texas on August 24, 2025. This was her second time preaching at this church.

Lorianne Willett, For USA TODAY

The stability Rochelle needed to care for her grandkids began to erode as soon as the state left them in her care.

Rochelle could not afford day care, so she relied on a state assistance program. In what would become a central contention with caseworkers, red tape and low rates effectively denied her childcare in the city where she worked and studied.

Without day care in Austin, Rochelle had to commute during heavy traffic, couldn’t pick up the kids promptly when they were sick and lost work hours. With her paychecks cut in half and state financial aid nowhere in sight, she couldn’t show the mortgage company enough income to keep her house out of foreclosure.

“After tying myself into a pretzel and losing everything I’ve worked for, the kids will still go into foster care,” Rochelle said days before her home was listed for public auction. “The department could have prevented all this.”

Mom. Nana. Seminarian.

Rochelle moved from California to Texas to save her son. She believed a fresh start in San Antonio would divert the teen from drug use.

Together, they enrolled in a family-oriented treatment program, and he graduated high school on time. She keeps his diploma and cap on display in her living room.

But then, the 19-year-old got his 17-year-old girlfriend pregnant. Jayden was born in 2023 and Briana a year later.

Rochelle knew the young couple struggled. As she’d learned in the 12-step program, she practiced “detaching with love.” She let her son take responsibility for his decisions while doting on the little ones and playing with them at the neighborhood park.

A photo of Rochelle and her son sits in her home in San Antonio on Aug. 24. In February, state child welfare workers placed her two grandkids into her care after removing them from her son and his partner.

Lorianne Willett, For USA TODAY

Around the same time, Rochelle had to decide whether to move.

She had been offered a full-ride scholarship to Austin Presbyterian Theological Seminary as part of a dual-degree master’s program in divinity and social work.

Rochelle had been raised by her aunt and uncle, a Baptist preacher, since she found her mother dead on the couch at age 12. God sustained her through grief and then college. Faith held her steady when the man she intended to marry disappeared, leaving her a single mom. Rochelle, a lifelong poet, eventually tired of writing verses for “a secular world.”

Rochelle never considered ministry for a career until she crossed paths with a professor who told her to apply anyway.

“My arms aren’t long enough to box with God,” she says with a grin, describing how everything fell in place too perfectly to ignore.

Rochelle shakes hands with a churchgoer after giving a sermon at First Presbyterian Church of New Braunfels, Texas on Aug. 24, 2025. She has been juggling full-time childcare with her studies in divinity.

Lorianne Willett, For USA TODAY

Still, she was a committed mother and nana. So Rochelle decided to commute to Austin rather than move.

When the Texas Department of Family and Protective Services asked her to care for her grandkids, Rochelle had one condition: day care support in Austin. She told the investigator she could not miss work or classes. Over the phone, the woman’s supervisor said an application would be expedited so she would have day care within five days.

With that promise, Rochelle signed a contract to become a “Parental Child Safety Placement.”

“Ain’t nobody give up on me. I had people in my corner. People praying for me. People pushing me along,” Rochelle later explained to her son. “I wasn’t going to give up on my grandchildren.”

Worrying

Late on a Thursday night in February, a caseworker dropped off the infant and toddler with no shoes and no diapers. Jayden had no clothes.

Rochelle immediately went to H-E-B for essentials: yogurt, crackers, vegetables, fruit and milk. She had to teach herself how to mix the baby formula, something she’d never done as a mother. She fretted over missing class the next day but had faith the state would help her keep her grandkids.

She committed to fill their lives with joy despite the crisis.

Rochelle laughs with her granddaughter Briana and grandson Jayden, in her home in San Antonio on Aug. 24.

Lorianne Willett, For USA TODAY

Rochelle used silly voices when reading books to Jayden. She sang Christian rock anthems to Briana while carrying her. Rochelle was disheartened that she could see Jayden’s ribs, but the former child nutritionist knew she could nurse him back to health.

Taking care of the kids was a privilege – hard work well worth it. She adapted her routine to study while they slept and sought flexibility from her professors on due dates.

Her classmates’ concern wore down her shield of privacy and silent shame, especially once the situation was impossible to hide. Rochelle returned to campus with two grandbabies and two bags – one filled with diapers and the other with books. Briana, fascinated with her feet, often took off her socks while Rochelle studied but never lost one because of her nana’s keen eye.

Without day care in Austin, Rochelle immediately began missing work. Her $15-an-hour job as an instructional aide had been enough to scrape together her mortgage payment.

After days of emails and text messages with several caseworkers seemed to go nowhere, Rochelle broke down. Hoping to make clear how urgently she needed help, she drove to the DFPS office in San Antonio with her grandbabies. Rochelle said she would leave the kids if the state could not pay for childcare in Austin.

Sandy Amaral, the supervisor who had promised her day care over the phone, came to the parking lot. She reassured Rochelle. Again, she said it would be resolved soon.

With that, Rochelle took her grandkids home.

“Why would I not believe them?” she said. “I thought they were supposed to help people.”

Waiting

Weeks later, Rochelle still had no childcare near her school.

An invisible line between Austin and San Antonio dictates where childcare aid can be used. Rochelle lived in San Antonio, so that was where she could receive state support. Not Austin.

Rochelle believed common sense would prevail. She sent emails. And text messages. And hammered on her need for day care in Austin every time a caseworker visited her home. She called supervisors’ supervisors and learned how to file official complaints.

It seemed to work.

At a day care around the corner from seminary, administrators said they would work with Rochelle and the state. Day care workers did extra paperwork to become a contractor of the program's San Antonio region.

But when the state sent the contract in July, the day care declined. The state wouldn’t pay enough and wanted to pay the bills a month behind.

After dozens of calls, Rochelle could not find a day care in Austin that would accept the offered terms. She could not afford to pay the difference.

In desperation, she accepted a San Antonio day care that just created different challenges.

Day care workers would not administer a nebulizer to Briana. They would not give Jayden children’s Tylenol. Kids were sent home if they had a cough. And so, Rochelle was often called for early pickup.Even when the kids were healthy, day care hours shaped Rochelle’s schedule, putting her in traffic at the busiest times. Some days she spent six hours on the interstate instead of three. Rather than letting the kids play while she studied in her office, the babies stayed longer in a day care almost 70 miles away.

Pay stubs show Rochelle only managed to work half as many hours because day care was in the wrong city.

At home at night, Rochelle would feed the kids and tuck them in. Briana slept in her son’s old bedroom. Jayden liked his living room crib better than the toddler bed.

Rochelle would drink a protein shake or eat leftovers if anxiety and exhaustion didn’t kill her hunger. She sat at the kitchen table with her laptop to send another email to child welfare officials. She crafted them with vivid language and calls to action on moral grounds much like a sermon. She bolded key phrases, wrote numbered lists and referenced dated documents.

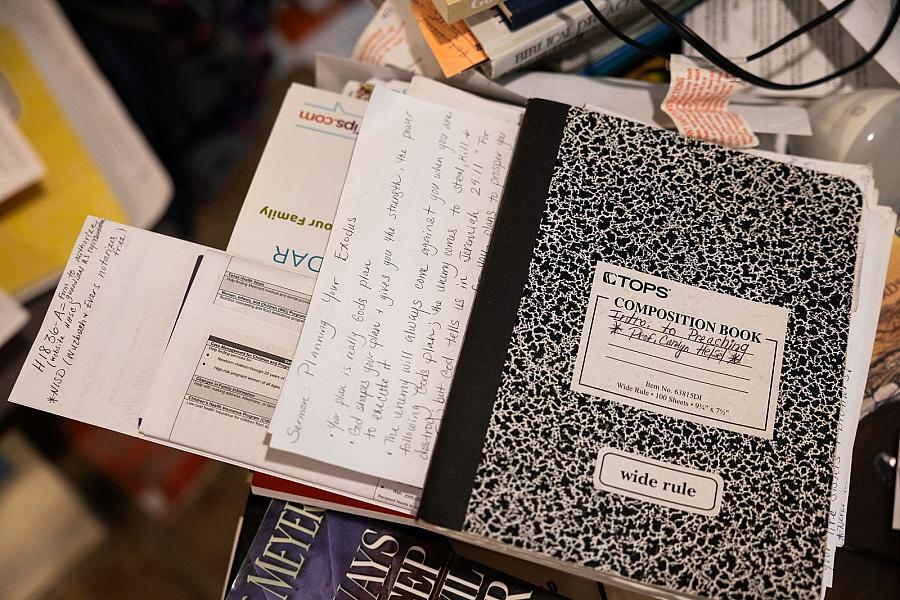

Rochelle's class notes and other writings sit on the table in her home while the counter is full of Briana's formula.

Lorianne Willett, For USA TODAY

In hundreds of communications reviewed by USA TODAY, Rochelle described falling behind on mortgage payments, needing help finding a day care in Austin and feeling disrespected by caseworkers.

“It seems like your department intends to see me struggle on purpose, sabotage me and my family on purpose, cause hardships on purpose,” she wrote March 31. “It feels 100% intentional, discriminatory & diabolical.”

Rochelle sometimes ended emails by refocusing on the kids or expressing hope for better collaboration.

“My goal is to seek the best and highest good for my grandkids in our family,” she wrote. “Thank you.”

Jargon

Rochelle didn’t know the legal jargon shaping her family’s lives, but those first few weeks the state was not, technically, responsible for the kids’ care.

“Safety plans” like the one Rochelle signed are celebrated by some child welfare experts for keeping kids with extended family while working with their parents to fix concerns. The approach bypasses government taking custody of kids and parents becoming tangled in lengthy court cases.

Other researchers and family law advocates call it “hidden foster care.” Government still tells families where kids should live and what they must do to get their kids back. Unlike a legal case, federal officials don’t track when kids change homes. Judges have no involvement. And, in most states, kinship caregivers receive no support services.

Rochelle makes food for her grandson, Jayden, in her home in San Antonio, Texas, on Aug. 24, 2025.

Lorianne Willett, For USA TODAY

In Texas, Rochelle might qualify for financial assistance if a judge ordered the state to take conservatorship of her grandkids.

That happened March 19.

At 2:49 p.m., a caseworker emailed Rochelle, telling her the case had gone from a voluntary safety plan to a legal case with involuntary foster care.

“It is urgent that we speak to you about the children’s placement and if they will remain in your care,” Lilliana Fuentes wrote. “We do need to hear from you in the next 30 minutes.”

At 7:24 p.m., Fuentes texted that she was driving to Rochelle’s home.

“We are in traffic,” Rochelle replied. “bc childcare is not in Austin.”

Soon after she got home, Fuentes arrived. She told Rochelle she had to sign a new placement contract. “If you don’t, I’m instructed to remove the kids,” Rochelle remembers her saying.

Fuentes sat at the kitchen table while Rochelle explained her need for Austin day care and changed Briana’s diaper. She asked what Fuentes could do to help as she fed Cheerios to Jayden, a quick meal that wouldn’t distract her from the conversation.

After talking in circles for three hours, Rochelle scrawled her name on the paperwork, adding “under duress.”

The kids would stay with her, for now.

Financial assistance would not arrive for months more.

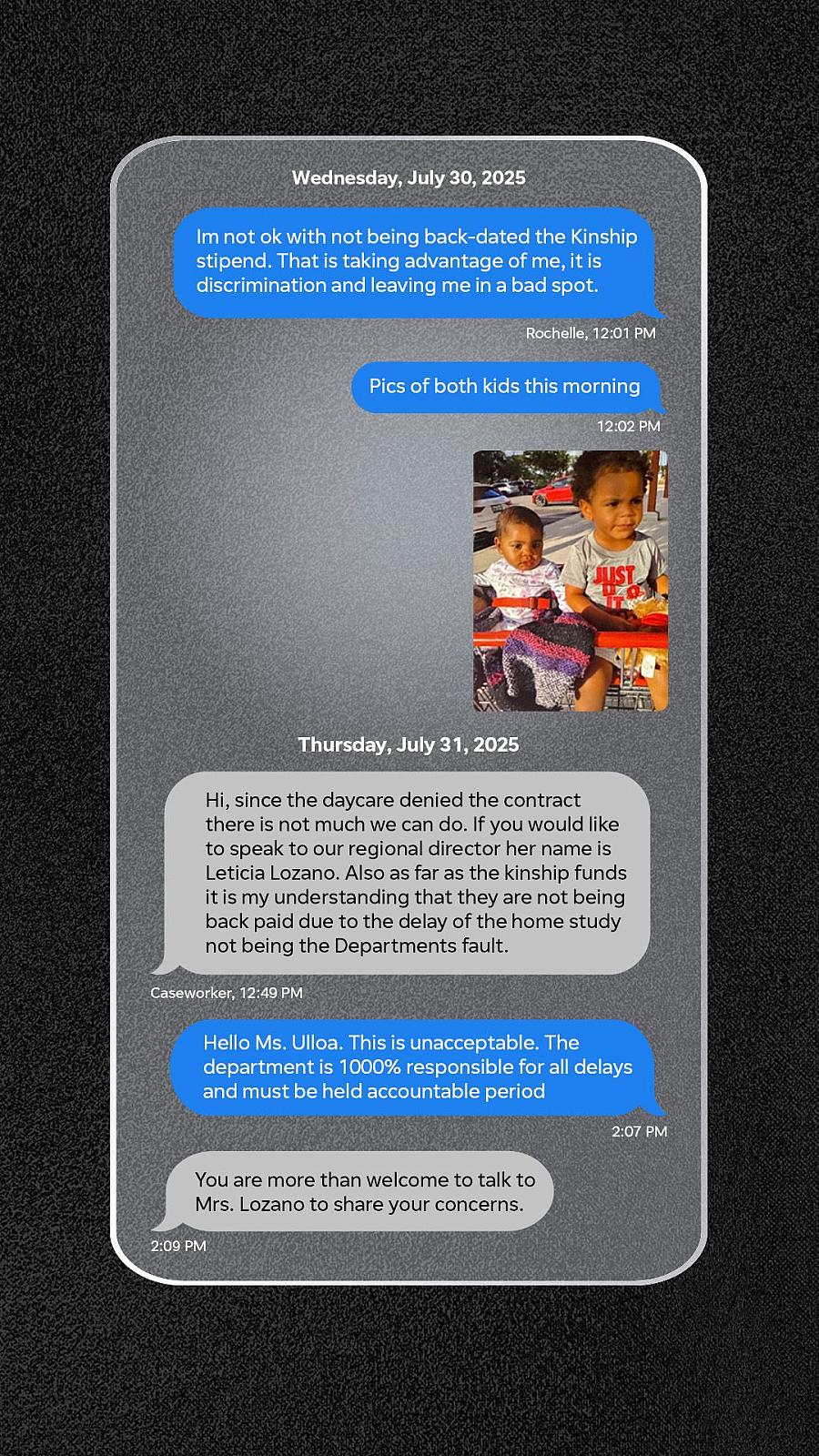

Photo illustration recreating a text conversation between Rochelle and a caseworker.

USA TODAY

Rochelle received her first “Kinship Maintenance Payment” at the end of July, days after receiving a letter from her mortgage company that she was entering foreclosure.

Those federally funded payments from the state are about $360 a month for each kid. Texas pays foster parents roughly $750.

Rochelle cared for her grandkids months without aid and her requests for backdated payments were denied. She is confused why.

Texas DFPS Field Director Lindsey Van Buskirk told USA TODAY that kinship payments should start from the first day of a legal case, not the day department paperwork is finished.

A spokesperson later clarified: “The process begins day one. Payments begin on the date the home study is approved.”

The department’s online policy manual describes required timelines. When caseworkers identify a kinship caregiver before kids are removed – like Rochelle was in January – they are supposed to complete the home study before the first court hearing, usually within two weeks of the state taking conservatorship.

Rochelle first heard the term “home study” in April but no one explained to her how it was different from the “home assessment” done by February. Department officials later told her in texts and emails that delays completing the more detailed review of Rochelle’s home were her fault.

“If my home was good enough on February 6th for these kids to be in my home all this time then I should be good enough to receive a backdated stipend. Because I’ve done the work,” Rochelle said. “They’re playing semantic and linguistic games. Policy should change.”

Rochelle pictured with her granddaughter Briana and grandson Jayden in her home in San Antonio on Aug. 24..

She did receive a one-time assistance payment of $1,000 after six months. Rochelle noted that equates to $136 a month for raising two kids.

In August, Rochelle told DFPS officials it didn’t make sense that the state could “be the legal parent” but not pay a dime to meet their needs. That would make the state “a negligent parent.” She wondered if state workers were trying to bully her to give up her grandkids.

“I have been patient, taken excellent care of the children … and cooperated with the home visits of random strangers in my home (9 different people so far), in addition to providing financially,” she wrote in an email. “Does anyone you work with have any common decency?”

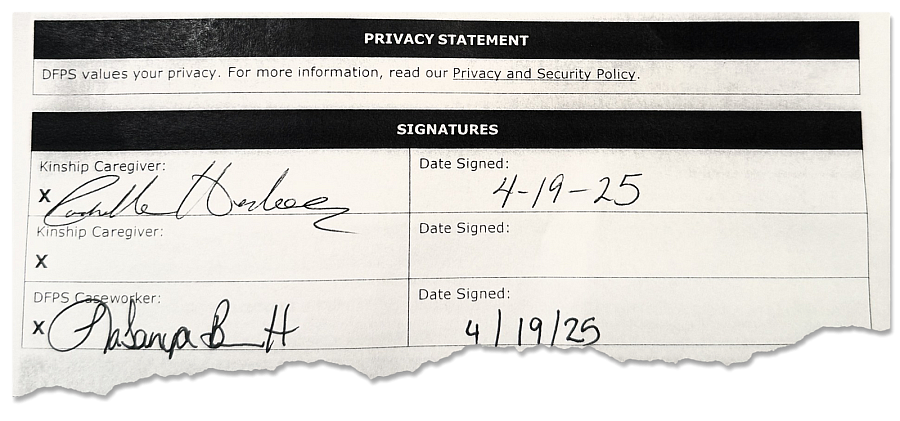

Deputy

In April, a month after the state took conservatorship of Rochelle’s grandkids, a new social worker – the 16th one she had talked with – visited her home.

Rochelle told Latanya Bennett that she still expected the state to place childcare in Austin – repeating the plea she had made in several text exchanges since the kinship worker joined the case a few days earlier. Rochelle described how it was straining her ability to pay the mortgage and afford basics.

Bennett followed up by texting Rochelle about a nonprofit offering free diapers. She explained that past help with things like formula were approved by the investigation supervisors but now her case was overseen by a different unit with different supervisors.

Two days later, a neighbor noticed a sheriff’s deputy parked in Rochelle’s driveway. He called to tell her.

Rochelle, who was studying at a neighborhood library, called dispatch to ask what was going on. She was told a DFPS supervisor reported that she had not let the department see the kids in more than a month. The sheriff’s office had been asked to take them.

Rochelle drove home and showed the deputy paperwork she’d received from Bennett during a home visit days before.

The document shown to a sheriff's deputy on April 21, 2025, which includes signatures for Rochelle and Latanya Bennett from two days earlier.

Courtesy of Rochelle

Satisfied, he left the kids with their nana.

That next day, a different caseworker, Dylan Powell, texted Rochelle that the kids were being moved to a new home and “daycare was not renewed.”

Powell had been assigned to take over as the children’s caseworker three weeks earlier. He had texted Rochelle twice and talked with her once on the phone but had not yet met her in person. She had texted him to “have a check” for her lost wages whenever he did come to her house.

Powell’s message saying he was coming to take the kids arrived while Rochelle was in Monday classes. Texts from a fill-in supervisor arrived from an unfamiliar number while she was commuting. Rochelle said she didn’t see the messages that day.

She learned day care was canceled Tuesday morning when workers would not allow her to drop off the kids. She took them with her to school and, once there, arranged to stay at a classmate’s Austin home for the week since she no longer had childcare.

In an email that evening, Rochelle asked Powell why the department would “disrupt the children” by taking them from her care. She told him it “feels like retaliation.”

“The process is confusing and seems unfair, with different people telling me different things while I am doing my best and I ask for help, but instead get treated poorly and attempted to be discarded like a stranger,” she wrote Powell. “Let us reset. I will be calling you soon.”

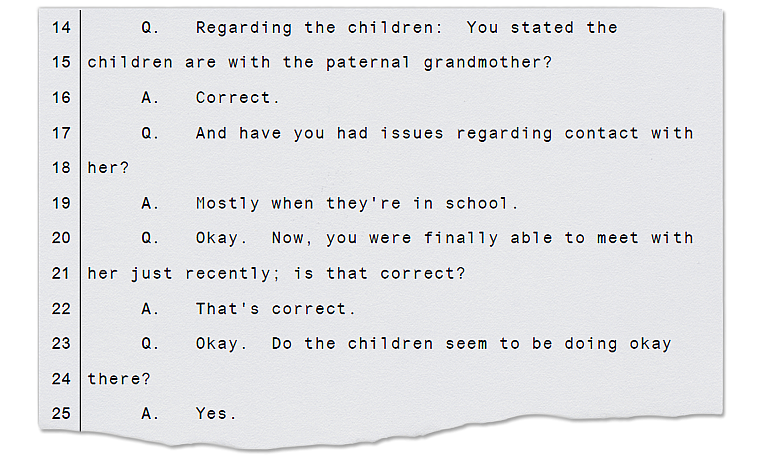

Powell agreed to start fresh after talking with Rochelle on the phone. At a May court hearing, he told the judge he had no concerns with Rochelle’s care and she was meeting the kids’ needs.

Powell visited her home once before a new caseworker was assigned to the family.

Excerpt from transcript of court hearing on May 19, 2025 where DFPS caseworker Dylan Powell testified he had no concerns about the kids living with their grandmother.

Courtesy of 131st Judicial District, Bexar County, Texas

Community

With the San Antonio day care contract canceled, Rochelle lost the routine she’d established. Just days before final exams, she scrambled.

Throughout it all, she had leaned on her faith communities to get by.

A woman from church filled four plastic totes with new clothes.

A classmate handed her H-E-B gift cards for groceries.

Another seminarian organized a rotation to watch the kids on campus while Rochelle was in class. A vice president was among those who helped.

In addition to helping raise her grandchildren, Rochelle is a master's degree student at Austin Presbyterian Theological Seminary. She stands fourth from right next to President José R. Irizarry in this group photo taken after a Sept. 30 service that was planned by Rochelle.

Courtesy of Rochelle

The academic dean approved multiple extensions so Rochelle could turn in coursework late without penalty. On a letter awarding her a scholarship for academic achievement and Christian character, the dean added a handwritten note:

“You are one of the strongest women I have ever met!”

One spring morning, Cherri Johnson was surprised to see her friend break down in tears minutes before a group presentation. Rochelle had spent all night at the hospital with sick kids and slept less than an hour.

“You could feel the hurt coming off her,” Johnson said.

It seems like a grandparent – anyone from a family – who is taking over should receive support. It’s for the children’s well-being to have a healthy, stable home. A familiar, family home.Cherri Johnson, friend of Rochelle

“It seems like a grandparent – anyone from a family – who is taking over should receive support,” she said. “It’s for the children’s well-being to have a healthy, stable home. A familiar, family home.”

Despite the frequent challenges kinship families face – particularly when unaided – decades of research shows kids do better living with loved ones than with strangers in foster care or through adoption.

They’re less likely to be abused in that new home and have fewer behavioral challenges. As adults, they are less likely to become homeless or incarcerated and more likely to work full time or attend college. They maintain a connection to their familial and cultural roots.

Fellow seminarian AJ Juraska said their experience as a foster parent was much easier than being a kinship caregiver “thrown in the middle of it.” Strangers who sign up to take in kids have months to prepare, receive training on how to navigate the state bureaucracy and know they are paid from the first day to cover the costs of an added child in their home. If foster parents give up out of exhaustion, it’s not on their own loved ones.

Juraska worries Rochelle is facing another challenge: discrimination.

“I don’t think, as a White woman, I would be treated the way Rochelle has been treated,” Juraska said. “It isn’t to claim any individual is racist. But the system.”

Texas has been repeatedlycalled out for Black kids being overrepresented in foster care.

In one 2011 study of Texas cases, researchers documented that White families with high-risk profiles were kept together and given support services at higher rates than Black families with similar risk profiles.

A spokesperson for the department denied “in the strongest terms any discrimination in this case.”

Juraska worries Rochelle is facing another challenge: discrimination.

“I don’t think, as a White woman, I would be treated the way Rochelle has been treated,” Juraska said. “It isn’t to claim any individual is racist. But the system.”

Texas has been repeatedlycalled out for Black kids being overrepresented in foster care.

In one 2011 study of Texas cases, researchers documented that White families with high-risk profiles were kept together and given support services at higher rates than Black families with similar risk profiles.

A spokesperson for the department denied “in the strongest terms any discrimination in this case.”

Keeping in touch

Rochelle also coordinated home visits with the children’s court-appointed attorney and the children’s special advocate. Her to-do list included making calls to childcare coordinators, day cares, doctors, developmental specialists, eight local nonprofits and her mortgage company. Once a week, the kids had supervised visitation with their parents.

Once a week during her commute, Rochelle listened to educational videos about prenatal health to qualify for free diapers from a San Antonio nonprofit.

She texted photos of the kids to parents and caseworkers: the grandbabies in the seat of a grocery store cart with a teddy bear; the kids with minor injuries after visiting another relative’s home; the formula bottle so caseworkers knew which brand to deliver to the day care.

“To brighten your day,” Rochelle texted a caseworker in February after sending a photo. Briana was kicking up her feet and watching Jayden mug for the camera, chubby cheeks raised high in a smile.

Rochelle plays with her granddaughter Briana in her home in San Antonio, Texas, on Aug. 24, 2025.

Lorianne Willett, For USA TODAY

Sometimes caseworkers canceled visits after Rochelle had cleared her schedule. Other times, she waited hours or days for a reply to learn department workers had been in training, had time off or had forgotten their work cell phone. Some state officials never replied.

Similarly, Rochelle sometimes took a couple days to respond when life was particularly hectic, like the week both kids had whooping cough and no one got any sleep. At least once, a text message to a caseworker didn’t go through because of reception issues.

In May, Rochelle’s phone ran out of memory. She could not receive new text or voice messages until she replaced it.

Planning

Rochelle called her aunt for comfort on many of her commutes.

Jennie told USA TODAY that she worried about her niece trying to do it all. The girl had always been headstrong. She held herself and the people around her to high standards. She wondered if Rochelle’s focus on principles over practicalities could come back to bite her.

“When you dealing with [the department], you got to learn: They’re over you,” Jennie said. “She messes up herself with her mouth, sometimes.”

Rochelle believed the state could be pushed to keep its day care promise but she was no longer planning on it by August.

The mortgage company offered her a new payment plan instead of auctioning her house, although it included adding about $40,000 in missed payments and legal fees to the loan’s principal. If she had not worked that out, Rochelle had been prepared to move into campus housing in Austin.

Rochelle signed up for fewer classes in her fall semester to have more time for the grandkids and all the mandatory department meetings. Between that, the course she had to drop and an incomplete internship, she would now graduate at least a year late and could not pursue the second master’s degree.

She would continue working as a chapel beadle and campus newsletter editor but would not be an instructional aide. The hours did not work with her caregiving responsibilities even though the income would have helped.

And, in August, Rochelle found a day care in Kyle, a town between San Antonio and Austin, that would accept the state’s contract. She completed a visit and enrollment paperwork so the kids could go when the fall semester started Sept. 2.

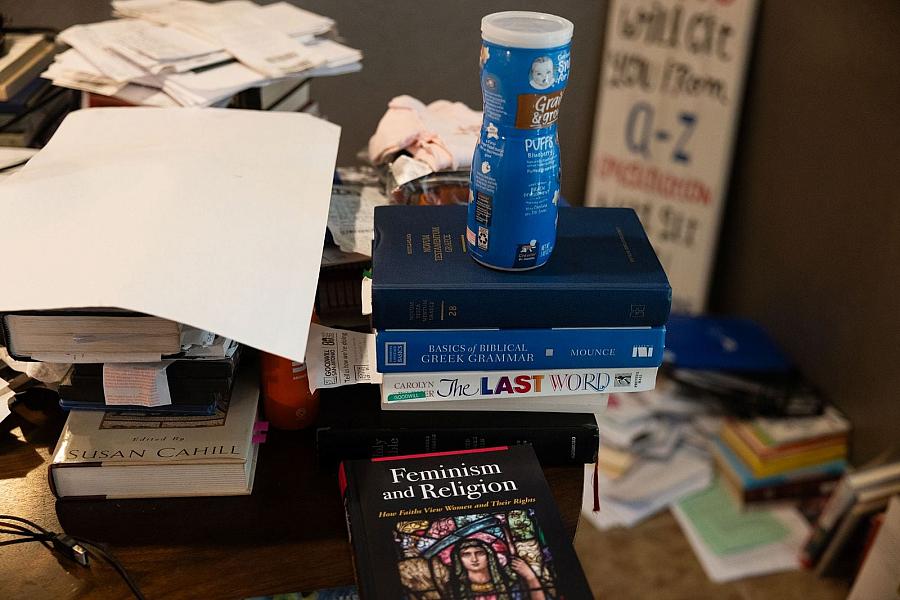

Religious books and baby snacks sit on a table at Rochelle's home in San Antonio on Aug. 24, 2025. She had her grandchildren placed with her through CPS in February, and has had a hard time trying to make her schedule work between kids, classes and her job. Rochelle drops off her grandchildren at a San Antonio daycare the morning of Sept. 19, 2025.

Lorianne Willett, For USA TODAY; Jayme Fraser, USA TODAY

But DFPS Program Administrator Tara Bledsoe told Rochelle on Sept. 5 that they would not approve a new day care until she met with several officials from the case.

“Good afternoon,” Rochelle replied. “I have responded to all messages from [the scheduler], including the note she left at my home in August. Whenever I call it goes to voicemail. I have left 4 messages total including today 9/8/25@8:30am.”

Back in classes, arranging speech therapy for Jayden and planning a service at the seminary chapel, Rochelle was swamped. She wasn’t sure when this gathering would happen but figured a caseworker would talk about it during the next home visit.

That would have to wait at least two weeks, the caseworker said, explaining she would be out of the office.

Rochelle said she understood. She also asked for patience making an appointment “as I adjust my schedule” with the start of school. “The department failed to fix childcare so time is very limited.”

The caseworker checked in on a Wednesday after returning from her time off, asking for a date to meet. Rochelle, busy with the kids, classes and a reporter shadowing her daily life, put off a reply until a slower day.

Frankly, Rochelle was sick of it all.

“Why would I want to talk to you? You’re making my life miserable.”

Monday

Rochelle was looking forward to a calm September weekend with the kids.

She didn’t deliver a sermon. She didn’t meet with a caseworker. Instead, she caught up on dishes and decluttered the kitchen counter.

Rochelle read Trish the Fish and several other stories Jayden picked from the couch-turned-shelf in her living room. Nana was proud of how, in eight months, the boy had gone from not speaking to having a vocabulary closer to developmental guidelines.

“I never tire of reading,” she said, pausing. “Actually, I have a six-book limit.”

Rochelle reads a book with her grandson, Jayden, in her home in San Antonio, Texas, on Aug. 24, 2025.

Lorianne Willett, For USA TODAY

Amid the busy start to school and continuing battles with the department, Rochelle relished quality time with her grandbabies.

“I always laugh at the wonder they express,” she said. “Briana is strong enough to mash her toy and see the lights and hear the music. She has her little grin when she pulls her mobile side to side.”

Jayden recently started calling her “mama” even though she only used “nana.”

On Monday, feeling a little more recharged, Rochelle did the usual: showered, got dressed, woke the kids, gave them baths and fed them, drove them to the San Antonio day care and – because traffic was mercifully light – made it to class in Austin just on time.

As Rochelle wrapped up chapel beadle rehearsal about 11:30 a.m., she texted the caseworker with a good time for a home visit that week. The woman did not reply.

Rochelle studied for a couple hours then got in her car for an early commute to pick up the kids from day care and diapers from a nonprofit’s office.

Rochelle's granddaughter, Briana, sits on the floor of her home in San Antonio, Texas, on Aug. 24, 2025. She is responsible for the care of both Briana and her grandson, Jayden.

Lorianne Willett, For USA TODAY

About 2 p.m. Rochelle got an avalanche of texts from her son that ping ping pinged. Moments later, her aunt called. She answered through the car’s Bluetooth system.

“They’ve taken the kids!” Jennie said. “They took the kids!”

Rochelle was confused. “What are you talking about?”

“They took them!” Jennie repeated. “You better call and figure out what’s going on.”

At 3:08 p.m., the caseworker Rochelle had texted that morning sent a reply:

“Hello. I wanted to reach out to you and let you know that we have picked up the children from daycare.”

Department officials would not tell USA TODAY why they removed Rochelle’s grandkids from her care on Sept. 22. They declined to tell Rochelle when she asked.

A spokesperson said the state would take a kid from a relative’s home for three reasons: that caregiver’s request, reunification with the parent, or safety concerns.

The children’s court-appointed attorney had told Rochelle in August that he did not want the kids attending day care in Austin. He said the children might need to live somewhere else if she was “not able to take care of" them.

Rochelle’s son was told his kids were taken because his mother did not talk enough with caseworkers. His partner was told Rochelle would not let caseworkers visit and she left the kids at day care too long.

Rochelle sits for a portrait after giving a sermon at First Presbyterian Church of New Braunfels, Texas on Aug. 24, 2025. She has been juggling full-time childcare with her studies in divinity, and said she is at the age where she should have been able to focus on herself.

Lorianne Willett, For USA TODAY; Jayme Fraser, USA TODAY

The night of the removal, Rochelle could not quite believe the state had stolen her grandbabies. She was emotionally numb from shock.

Her heart rate spiked to 191 – a figure that doctors say requires immediate medical attention.

Looking around her quiet home, Rochelle saw Jayden’s push car, the one he drove with his feet.

On the living room floor, Briana’s baby bouncer sat still and empty.