The Gaps in Care: What SoCal Chinese Mothers Reveal About a System Still Learning to Listen

This article was originally published in World Journal with support from our support from our 2025 Impact Fund for Reporting on Health Equity and Health Systems.

For many Chinese mothers in Southern California, the U.S. healthcare system remains difficult to navigate — with limited translation, fragmented information, and few providers who understand Chinese traditions around childbirth and recovery.

(Courtesy of Ada Teng)

When Fen Chen gave birth to her first child seven years ago, she did what she thought made sense: she chose a large, well-known health network in Los Angeles County.

After more than a decade in the United States, she still found the medical system hard to read. “I didn’t really know which kind of hospital I should trust,” she said. “Everything here feels complicated, so I just picked the one that seemed famous.”

But Chen’s experience left her uneasy. The hospital’s online reservation system was confusing, and she rarely saw the same doctor twice. Appointments came one after another — so frequent that she began to question whether they were necessary, yet no one explained why. The waits were long, sometimes hours, and at one location the staff seemed particularly indifferent. “Sometimes the doctor just asked two questions and let me go,” she recalled. “The nurses were cold. One even joked in the delivery room, saying, ‘Chinese people don’t even know their blood type.’”

Midway through her pregnancy, Chen was diagnosed with gestational diabetes after a routine blood test, but in the later weeks, no one followed up. She wasn’t sure whether she had missed an instruction or whether the doctors had simply overlooked her case. By then, she felt trapped — unsure whether to blame herself or the system, and too anxious to start over with a new provider. “You feel like you have no choice but to trust the system you’re already in,” she said.

For many Chinese mothers in Southern California, her story feels familiar. Even after years in the U.S., they face a healthcare system that remains difficult to navigate and rarely reflects their culture or language. The barriers are subtle but constant—limited translation, fragmented information, and a lack of providers who understand Chinese traditions around childbirth and recovery.

A web of rules and routines promises care but often leaves them feeling unseen and insecure.

Navigating an Uneven System

Lily Wang, an asylum seeker from China who arrived in the Los Angeles area in 2023 while pregnant, quickly discovered how intimidating the U.S. medical costs could be.

When she began looking for prenatal care, the doctor she contacted quoted between $8,000 and $9,000 for delivery—far beyond what her family could afford. “If we had paid that amount, we would have had almost nothing left,” she said.

With help from AJSOCAL (Asian Americans Advancing Justice Southern California), she learned she was eligible for Medi-Cal, the state’s public insurance program for low-income families, which covered her prenatal visits and delivery. “We were so relieved,” Wang said.

But her experience at the hospital still left her unsettled. Labor began around 5:30 a.m., but despite her requests, the anesthesiologist refused to administer pain relief, saying the shift was ending and no replacement was available. Her baby was born about an hour and a half later — without any anesthesia. “My wife was extremely painful,” Wang’s husband said. “The nurse told me the anesthesiologist didn’t want to work anymore because it was time to change shifts.”

Lily Wang says the anesthesiologist on duty refused to provide an epidural during her delivery, citing the end of his shift. She gave birth in severe pain and later filed a complaint with the hospital, but has yet to receive a response.

(Courtesy of Lily Wang)

Afterward, the hospital sent Wang a satisfaction survey. She filed a complaint describing what had happened, but months later, she still hadn’t received a response.

Wang and her husband rely on his night-shift wages and Medi-Cal for basic care for their new family. But because of their immigration status, they hesitate to apply for other support, like CalFresh and CalWORKs. “We’re afraid,” she sighed. “Afraid they’ll find us. Afraid it’ll hurt our case.”

That fear echoes through the community. He Xi, whose husband already holds a green card, waited months before applying for Medi-Cal and WIC because she is still waiting for her own green card approval. “I was afraid of being perceived as a ‘public charge’, and if it would impact my immigration status.

Baby clothes of He Xi’s child. Despite her husband’s permanent residency, He hesitated months before applying for Medi-Cal, fearing it might affect her own green card application.

(Courtesy of He Xi)

A 2023 Urban Institute study found that one in six immigrant parents avoided public programs because of immigration status concerns. Research in Social Science & Medicine reported similar findings among undocumented Californians, many of whom skip care altogether to avoid scrutiny.

The policy landscape adds to the uncertainty. Starting in 2026, new undocumented adults will no longer be able to enroll in full-scope Medi-Cal. Maternity and emergency services will remain protected, but programs like Food4All have been delayed amid budget cuts. Those already covered can keep their benefits, though beginning in 2027 they’ll have to pay a $30 monthly premium.

Even families with stable status and private insurance often find the system draining. Emma Shen, a Ph.D. candidate with an upper-middle-class household income, said her postpartum months were consumed by billing disputes and calls with her insurer. Some charges seemed inflated, and though insurance companies were often willing to lower them, the negotiation was entirely up to her.

“After childbirth, you’re exhausted, yet you have to chase down every bill,” she said. “It makes you realize how much responsibility the system puts on families — especially mothers.”

What Shen wanted the most was transparency: an information session before delivery explaining likely costs and how coverage worked. “Insurance companies should take initiative,” she said. “Pregnancy and birth are complicated, and most people don’t have the medical literacy to question every charge. You just end up paying what they tell you.”

She tried contesting a few bills but soon gave up — too tired to argue, too unsure what was right. In the end, she said, it was easier to pay and move on.

Interestingly, public insurance can sometimes work better than private. After her disappointing first delivery, Chen hoped to find a Chinese-speaking doctor for her next pregnancy — someone who could better understand her concerns and communication style.

In 2021, after she and her husband lost their jobs during the pandemic, they switched to Medi-Cal. To her surprise, it was through this program that she finally found the kind of care she had been looking for. Following friends’ recommendations and online reviews, she found a Taiwanese doctor in Monterey Park who accepted Medi-Cal.

The clinic was crowded and the waits were long, but the experience felt far smoother than before. “Everthing felt right this time,” she said.

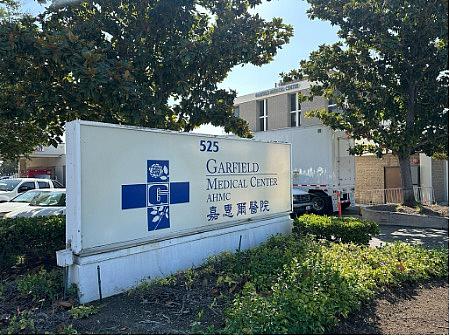

After an unsatisfactory first birth at a major hospital, Fen Chen chose Garfield Medical Center in Monterey Park — with many Chinese-speaking staff — for her second delivery, which went smoothly.

(Photo by Ziwei Liu)

Her experience underscores a paradox many immigrant families describe: that the safety net intended for those with the least can, at times, feel more accessible and humane than the expensive private systems meant to represent the best of American healthcare.

Lost in Translation

For many Chinese mothers, getting insurance or appointments is only half the battle — the harder part begins once they sit in the doctor’s office.

Ting Xiao, who has lived in the United States for more than ten years, speaks fluent everyday English. Yet during childbirth, she struggled to make sense of medical documents full of jargon. The hospital offered a Chinese translation, but it read like a machine output — stiff and confusing.

After her baby was born, her parents came from China to help with childcare. They were in their sixties and spoke almost no English. When they took the baby to medical appointments, the visits quickly turned tense. “There were no Chinese-speaking staff,” Ting said. “My parents got nervous, and the doctors were in a hurry. Everyone left frustrated.”

A 2023 study by May Sudhinaraset at UCLA’s Fielding School of Public Health found inadequate language support to be one of immigrant mothers’ biggest barriers to care. Although California law requires interpretation, many hospitals fall short. Mandarin speakers often rely on relatives or phone apps, approaches that risk serious misunderstanding.

Sudhinaraset said the issue is structural, not cultural: too few bilingual clinicians, limited interpreter training, and underfunded programs that treat language access as optional. Federal changes in recent years — particularly during the Trump administration, which rolled back translation requirements and promoted an “English-only” approach in agency guidance — have deepened the language-access challenge for immigrant patients.

“Translation is only the beginning,” she said. “The real challenge is whether providers can communicate in a way patients actually trust.”

Priscilla Hsu, an Asian American doula who supports women through labor and recovery, sees these gaps up close. She noted that most hospitals now provide some training in culturally sensitive care, but what she observes in practice often falls short.

“In Chinese culture, warmth symbolizes recovery,” she said. “But in U.S. hospitals, nurses hand you ice water, and the rooms are freezing. When patients refuse it, staff sometimes look confused — even suspicious.”

Pain management, too, reflects a clash of customs. “We use warm compresses,” Hsu pointed out. “Here, it’s always ice.” It might sound trivial, she added, but such details matter.

Priscilla Hsu noted that while hospitals often focus on “cultural sensitivity training,” many still fail to understand the everyday practices and preferences of Asian patients.

(Courtesy of Priscilla Hsu)

Hsu believes that when patients’ preferences and cultural needs are dismissed in moments of vulnerability, the loss of control can be traumatic — leaving them feeling unseen and powerless.

Where Care Finds Warmth

When care at hospitals feels cold and distant, many Chinese mothers turn elsewhere — to community clinics, nonprofit groups, and even social-media networks where language and trust come more easily.

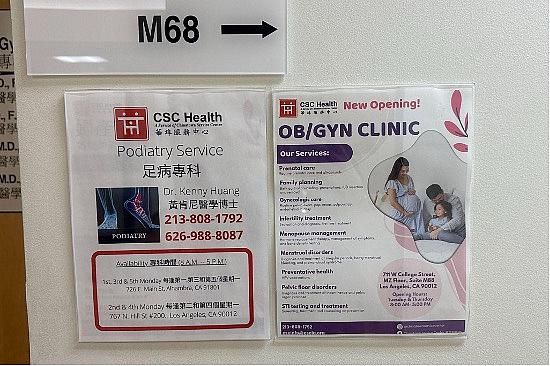

One of the most established is the Chinatown Service Center (CSC) in Los Angeles, founded more than half a century ago. “We never turn anyone away, no matter their insurance or immigration status,” said Jack Cheng, the center’s chief operating officer.

Chinatown Service Center provides prenatal and postpartum care, OB-GYN services, mental-health counseling, nutrition consultations, and social-work support — all available in Chinese.

(Photo by Ziwei Liu)

CSC offers prenatal and postpartum care, OB-GYN services, mental-health counseling, nutrition programs, and social-work support — all available in Chinese. For speakers of other languages, interpreters are arranged. Fees are based on income, and staff help families apply for Medi-Cal, WIC, and other benefits.

“Many immigrant mothers feel isolated or misunderstood,” Cheng said. “We want them to know they’re not alone. This is a safe place.”

Among the physicians at the Chinatown Service Center is OB-GYN Dr. Martha Vidal, who trained in both Mexico and the United States and has practiced in Los Angeles for more than twenty years. “As an immigrant myself, I approach every patient with the same respect,” she said. Though not Chinese, she works to meet her patients halfway.

“Some women won’t leave the house after childbirth, afraid the wind will harm them. Some eat only soups or tie red ribbons around their waists to protect the baby,” she said. “I respect that — it brings them comfort. But I also explain, medically, what’s safe and what’s not. Culture isn’t a barrier; it’s a bridge.”

Martha Vidal, who practices at the Chinatown Service Center, believes understanding cultural traditions helps build trust with immigrant patients. “Culture isn’t a barrier,” she said. “It’s a bridge.”

(Photo by Ziwei Liu)

Other community clinics, such as the Herald Christian Health Center and the Tzu Chi Medical Foundation, serve similar roles, providing bilingual staff and culturally aware maternal-health services. Advocacy groups like AJSOCAl help new immigrants navigate legal issues and access care.

Beyond formal institutions, informal support flourishes online. Many Chinese mothers turn to WeChat, China’s dominant messaging and social-media platform, and Red Note (known in Chinese as Xiaohongshu), a lifestyle-sharing app popular among the diaspora. There, they trade doctor recommendations, postpartum tips, daycare reviews, and policy updates — conversations that often feel more personal than any official channel.

Through community clinics, nonprofits, and online forums, immigrant mothers have carved out spaces of care that feel familiar, respectful, and safe — underscoring cultural connection as healing.

The Invisible Asian

Yet the reach of these community networks remains limited. For a population as large and diverse as Southern California’s Asian community, the demand for culturally and linguistically competent care far exceeds what small clinics and volunteer groups can provide.

“There’s real inequality in who gets care,” said Melissa Withers of USC’s Keck School of Medicine. “Asian immigrant women are less likely to be screened for depression, and even when they show symptoms, they’re less likely to receive treatment.”

Most county health programs, she noted, focus outreach on Spanish-speaking populations. Home-visit initiatives and community health workers seldom extend into Asian neighborhoods, leaving a silence that data often fail to capture.

Sudhinaraset of UCLA calls it “an invisible gap.”

“It’s tied to the ‘model-minority’ myth,” she said. “People assume Asians are educated and financially stable, so they don’t need help. That assumption shapes how funding is distributed.”

Led by May Sudhinaraset, the BRAVE research team focuses on how Asian immigrants are often rendered “invisible” in legal status and public policy.

(Courtesy of May Sudhinaraset)

A joint UCLA–AAPI Data report found that Asian American, Native Hawaiian, and Pacific Islander families participate in public programs such as Medi-Cal and CalFresh at far lower rates than their eligibility would suggest. Researchers attribute this to language barriers, cultural stigma, economic instability, and a shortage of culturally matched providers.

Even the label “Asian,” Sudhinaraset added, masks diversity. “When we lump everyone together, the most vulnerable disappear. Without disaggregated data, policymakers assume there’s no problem — and that invisibility just repeats itself.”

The result is a quiet cycle: underrepresentation leads to underfunding, which deepens the neglect.

That neglect is not only measured in data but felt in delivery rooms, clinics, and homes — places where mothers like Fen Chen live its effects.

“If I could start over,” she said, “I probably wouldn’t choose to become a mother here.”

Her exhaustion came from years of navigating a maze of appointments and bills, doing every bit of research alone, and facing pregnancy without nearby family or a supportive partner. What should have been a season of joy became a lonely test of strength in a system that never quite understood her.

To help bridge the information gap for Chinese immigrant mothers in Southern California, the reporter created “Mom Support LA” — a Mandarin-language guide to maternity resources and public programs in Southern California: https://www.momsupportla.com/