Crisis intervention training puts Muskegon educators a step ahead

The story was originally published in Detroit Free Press with support from the USC Annenberg Center for Health Journalism's 2022 National Fellowship.

Image from Detroit Free Press article

Image from Detroit Free Press article

Sometimes students kick.

They scratch. Or they throw things.

Student aggression in the classroom can spin out of control quickly and test educators’ ability to de-escalate in the moment. But a student's actions or demeanor that usually precipitate such behavior can also be the signal to identify a student at risk of experiencing a crisis before it happens.

“I try my best to make sure that I'm as calm as possible when I'm in those situations,” said Jasmine Allen, an elementary school special education aide in Muskegon Public Schools.

On a Monday in October, Allen joined more than a dozen other educators in west Michigan for Therapeutic Crisis Intervention for Schools (TCIS) training, a multiday course for educators on how to proactively prevent aggressive behavior and other dangerous outbursts in schools. Advocates of TCIS training say it can help to make school a safer place for both students and teachers and lead to a decline in dangerous situations.

Muskegon Public Schools learn de-escalation tactics

Members of the Muskegon public school system learned best practices in building relationships with students and de-escalating potential issues in the classroom.

Administrators in the Muskegon school district believe this approach — proactively trying to prevent classroom crises — reduces the chances that staff will use restraint and seclusion on students. Restraint is when an educator physically limits a student’s movement using force, while seclusion entails an educator isolating a student in a room. Both practices are known to traumatize children.

And in Michigan, as a recent Detroit Free Press investigation found, those tactics are used at rates that alarm many educators and behavioral professionals. Teachers in Michigan used restraint and seclusion nearly 94,000 times in the past five school years, even after the state Legislature tried to Muskegon’s success is evident in the data: The district has reduced the number of students restrained annually by 70% since focusing on training over the past three years.

In November, Gov. Gretchen Whitmer said the state’s laws surrounding these controversial tactics should be improved, following the Free Press investigation into restraint and seclusion, which showed the Legislature’s 2016 efforts didn’t include any consequences to hold schools accountable for breaking the law.

The law also required districts to analyze seclusion and restraint data in order to reduce their use of these practices, but gave no state agency the power to enforce that requirement.

The Free Press asked more than a dozen districts for any such local analysis. Only two responded with their analyses.

Muskegon is one of the districts scrutinizing its data.

Christine Robertson, director of specialized instruction for Muskegon Public Schools, attributes the district’s success to careful data-gathering and thoughtful, continued training.

“I think a lot of people initially were a little afraid of this law,” she said. “But really, the only time we should be using it is when the student is a danger to themselves or others.”

Kindness before a crisis

Leanne Bauer, an instructional coach for special education at Muskegon who helps train educators in TCIS, said active listening and other techniques she has learned have been a game changer.

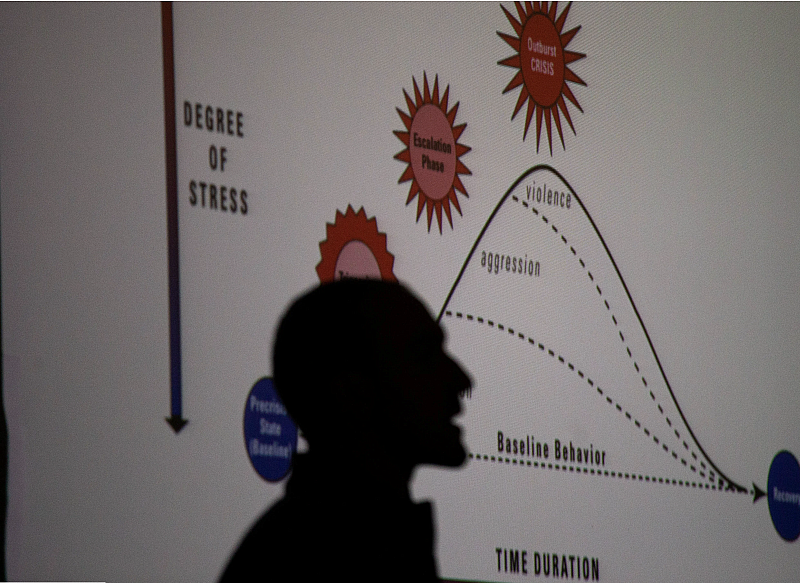

Bauer said when she was first trained five years ago in TCIS, she noticed she was better at identifying when a student was at risk of having a meltdown.

“I was better able to see that a kid was triggering and escalating up to that point,” she said. “A lot of times back then, it would go from, ‘Where did that come from? I didn't see that come from anywhere, now I'm in a full-blown crisis, right?’ And now I'm able to see, ‘Oh, they're starting to trigger, I need to stop right here and work with the kid so we don’t get here.’ You just notice more.”

Muskegon fully implemented TCIS training at the elementary school level in the 2019-20 school year. In the school year before, 2018-19, educators secluded or restrained 18 students with disabilities. In 2019-20, educators secluded or restrained 27 students — an expected increase due to better record-keeping, Robertson said.

On the final day of training, educators learn techniques to restrain students — training materials caution that such a practice should be used only when a student’s behavior could imminently cause an injury. This part of the training is intended to reduce the risk that a student is injured while being restrained, Holden said.

TCIS isn’t the only training that exists to help educators who work with aggressive students.

The Crisis Prevention Institute (CPI) also offers training — Livonia Public Schools has trained teachers, paraprofessionals, administrators and bus drivers using CPI training, said spokeswoman Stacy Jenkins. Livonia reported secluding or restraining fewer than 10 children every year such reporting was required, according to state data.

Finding the funds for training

The law passed in 2016 requires public school districts to adopt a “comprehensive training framework” that includes de-escalation techniques, proactive strategies for behavior management, identification of events that might trigger an emergency for a student, methods for evaluating whether the risk of harm calls for the use of restraint and seclusion, the impact of restraint and seclusion on a student and more.

However, as occurs frequently in Lansing, lawmakers failed to provide any money specifically for that training.

“Not only would districts have initial costs for training staff on the new policies, they also would likely need to provide ongoing training to ensure that the administration, staff, and especially key identified personnel continued to adhere to the new policies and keep up-to-date on current positive behavioral intervention strategies,” states a Senate Fiscal Agency analysis of the legislative package.

The House Fiscal Agency suggested some training costs districts $2,900 per person. Initial TCIS training can cost as much as $34,000, according to a training brochure, while refresher courses can total $12,000.

Earlier this year, the Legislature and Whitmer agreed on a measure that provides $22.2 billion for Michigan students. It’s the largest education-related budget in state history, buoyed substantially by one-time federal funding following the COVID-19 pandemic.

While the measure does include some grant funding that intermediate school districts can use to implement a specific kind of training for mental health professionals in these schools, it does not allocate any funding specifically for programs like TCIS or CPI that aim to reduce the use of seclusion and restraint by training a much broader swath of educators.

The 2016 law also doesn’t provide any enforcement of the training requirements and doesn’t track who receives the training. Bill DiSessa, a Michigan Department of Education spokesman, wrote in an email that his agency doesn’t have the “authority to enforce training requirements, nor track school personnel training.”

Whitmer’s communications director recently said after publication of the Free Press investigation that “it’s clear” laws regulating seclusion and restraint can be improved. The incoming leader of the Michigan state Senate agreed, pledging to bring people together during the next legislative session to discuss possible changes.

Christine Greig, former House Democratic leader, recently suggested lawmakers can and should use the threat of withholding future money to cajole school districts to comply with seclusion and restraint laws.

“It’s tough to do to schools, but you can always use the power of the purse. If they’re not reporting things and complying, that there’s some kind of funding implications,” Greig said.

But funding may not stop every educator from turning to restraint and seclusion too often. Holden, the TCIS expert, said she has been to schools overusing those tactics with plenty of resources but little emphasis on putting training into practice.

“The best thing is to have adequate resources and a well-trained, competent workforce and then you have fewer problems,” she said.

‘Not about being right or wrong’

Training in Muskegon is ongoing. Educators become certified in a four-day, 28-hour program, then must take annual refresher courses to retain the skills and strategies they learn.

Muskegon educators in October discussed questions everyone should ask as they see tension rising within a student: What am I feeling now? What does this student feel, need and want? How is the environment affecting the student? How do I best respond?

Tracey Knight, one of the trainers and a behavioral support specialist within the district, said children are “extremely observant” and know when an adult can appear emotionally distressed, which can further make a child feel emotionally distressed.

Some students can become emotionally aggravated when they need help with something, but don’t want anyone else in the classroom to know. Small problems can turn into big problems fast when a student is emotionally distressed.

“When you explore what the student has experienced, it leads to empathy and a better understanding,” she said. “Sometimes kids just want to be safe, feel safe, be treated fairly, and the desire to feel accepted by someone.”

October’s session in Muskegon was Allen’s first time attending a TCIS training. As a paraprofessional who works with students with disabilities, she helps students between classes and supports them during gym and recess, plus other special classes.

Some days — when students try to run away from her or act aggressively — can be emotionally draining. She already knows that it’s important to stay calm in a crisis. But with TCIS, she said, she’s building on that knowledge to avoid a crisis in the first place.

“It's not about being right or wrong, necessarily,” she said at the October training. “It's about approaching the situation in a way that's going to help you succeed at the end goal, which is typically to de-escalate, or to get the kid to be ready to learn.”

Did you like this story? Your support means a lot! Your tax-deductible donation will advance our mission of supporting journalism as a catalyst for change.