Culturally Tailored Subsidized Lunch Programs for Seniors: A Critical Health Need

The story was co-published with AsAmNews as part of the 2024 Ethnic Media Collaborative, Healing California.

Seniors at Yu-Ai Kai Japanese American Community Senior Service in San Jose, Calif., enjoying nutritious lunches.

Photo by Jia H. Jung

On a rainy Veteran’s Day, Japanese elders ducked into the Yu-Ai Kai Japanese American Community Senior Service center in the heart of San Jose’s Japantown, ascending to the dining hall on the second floor.

This is one of 37 sites offering subsidized lunches across Santa Clara County to people over 60 years old. Many of the 65 or so folks who partake daily in Yu-Ai Kai’s weekday senior lunches are Asian elders on fixed incomes. Here, they benefit from food that meets their nutritional needs and preferences at an affordable price and in a social atmosphere.

Yu-Ai Kai’s all-Asian menu boasts stalwart Japanese dishes like tonkatsu (豚カツ) – lightly battered, deep-fried pork cutlets, yaita sake (焼いた鮭) – grilled salmon, and yaita saba (焼いた鯖) – grilled mackerel. Chinese favorites such as Kung Pao chicken and Pork Mabo Tofu and Filipino chicken adobo make cameos, too.

Setsuko Kubo works as a kitchen aide after serving as the in-house SNP cook at Yu-Ai Kai for many years. Her Japanese comfort foods include ohagi (おはぎ) sweet rice balls, sekihan (赤飯) red bean rice, zaru soba (ざるそば) cold dipping noodles, and tempura (天ぷら) lightly battered fried seafood and vegetables.

Photo by Jia H. Jung

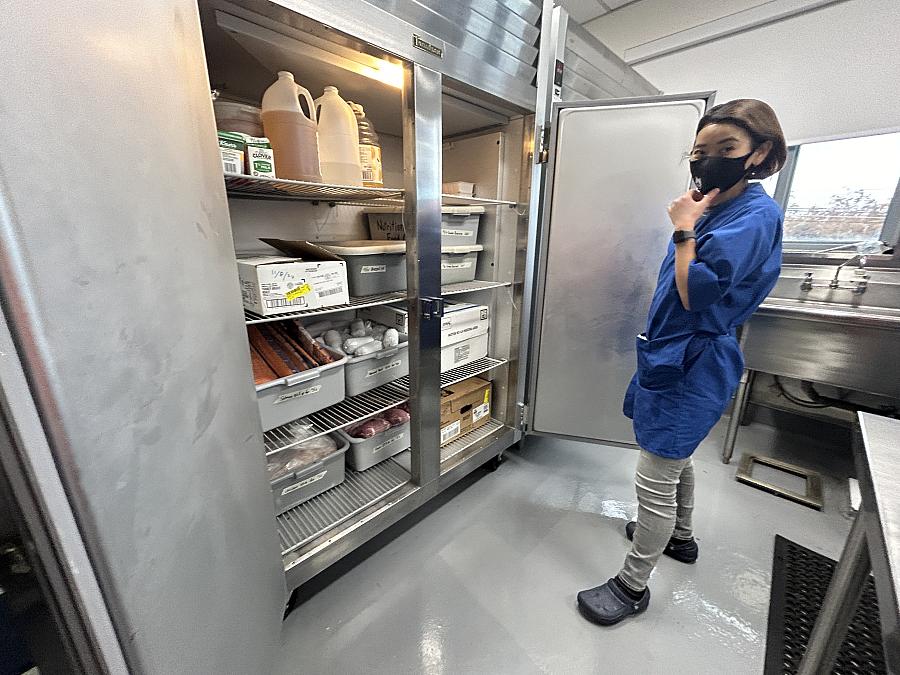

Yu-Ai Kai’s new cook Hiromi Moriyama gets a delivery of salmon into the fridge. Her Japanese comfort foods include soba (蕎麦) cold buckwheat noodles, yakitori (焼き鳥) chicken skewers, and Japanese sweets.

Photo by Jia H. Jung

According to the hunger relief organization Feeding America, Asian elders in the U.S. are twice as food insecure as their White counterparts. Culturally attuned community organizations and Asian-owned businesses in the county have been addressing this disparity by helping counties fine-tune how to implement federal senior nutrition initiatives for their diverse communities.

The blandness of a top-down approach to senior food insecurity

California has some of the highest costs of living for retirees in the U.S., yet it is an AARP-designated age-friendly state with the largest and fastest-growing population of older adults in America.

The state projects that the population of residents aged 65 and up will double to 8.6 million over the next five years. By 2030, approximately 10.8 million people – 1 of 4 Californians – will be over the age of 60.

The Older Americans Act (OAA) became law in 1965 to promote the independence of America’s senior population. Amendments in 1972 created a nationwide Senior Nutrition Program (SNP), structured to operate with both public and private funding.

California’s implementation of this is the Older Californians Nutrition Program (OCNP), under which federal grant awardees, often county and city agencies, decide how best to help local seniors access food.

The three modes of SNP delivery are monthly food boxes distributed to qualifying senior households, home-delivered meals colloquially known as Meals on Wheels, and congregate dining held in community spaces.

Yu-Ai Kai’s Meals on Wheels lunch delivery assembly line hustles while drivers wait on the side.

Photo by Jia H. Jung

Meals for all modes of service must meet Dietary Guidelines for Americans and provide a minimum one-third of professionally determined Dietary Reference Intakes per meal, while fulfilling any further specifications of county nutritionists.

SNPs can have a “one-size-fits-all” approach because of all the people they have to serve, receiving popular criticism all around the country for serving bland, institutional Western food options to old folks who aren’t in a position to be choosy.

But cultural food preferences are more than luxuries; they are health needs.

The Public Policy Institute of California predicted that food insecurity among Asian seniors will increase by 118% by 2030. Kayla de la Haye of USC’s Institute for Food System Equity noted that disproportionate food insecurity among Asian elders exists because the state’s food environment fails to provide what they need.

Senior lunch at the India Community Center in Milpitas, Calif.

Photo by Jia H. Jung

Research states that lack of access to culturally sound and nutritious food significantly intensifies Asian elders’ already heightened vulnerability to clinical depression.

Poor nutrition also leads to malnutrition from food deprivation and a host of other health problems, including a heightened risk of diabetes, hypertension, and heart disease, which, after cancer, are already leading killers of Asian people over 65. These illnesses are widely known to be food-system-related, and scientifically proven to be triggered and exacerbated by the sugar, processed ingredients, empty calories, and fat typical of most mass-produced diets.

Meanwhile, statistics published by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention show that Asian people have the highest rates of osteoporosis after age 50. And, according to a study published by the British Medical Journal, lactose intolerance affects nearly 100% of adults descended from most Asian and Native American subgroups, compared with 50-80% of Hispanics, South Asians, Black people, and Ashkenazi Jews, and 25% of white people.

This means that most Asian adults cannot benefit from the milk or other dairy products served by their counties.

Yu-Ai Kai’s fiscal manager Sara Fritts opening up the milk fridge.

Photo by Jia H. Jung

Small kitchen, big difference

Santa Clara County is where a significant concentration of California’s Asian communities outside of Los Angeles live. The county is also home to a handful of culturally responsive SNPs that show how local nutrition policies can reach more of its community.

Yu-Ai Kai, which celebrated its 50th year anniversary in March just months before Santa Clara celebrated 50 years of its SNPs, has been cooking senior lunches in-house for almost just as long.

Yu-Ai Kai Japanese American Community Senior Service at 588 North 4th Street in San Jose, Calif.

Photo by Jia H. Jung

Being county-funded means the Yu-Ai Kai cooks have a lot of rules to follow, such as daily servings of vitamin C and vitamin A three to four times a week, and no chicken two Mondays in a row.

“It’s like this puzzle that the cook has to figure out,” said nutrition site manager Maya Futamura. She worked for Kimochi Senior Center in San Francisco’s Japantown in the same role before relocating to the South Bay. In 2016, she answered a vacancy at Yu-Ai Kai, replacing an employee who spent 40 years on the job before retirement.

“I made sure to respect the history, and I didn’t want to be all pushy with changes, because I don’t work in the kitchen,” Futamura said.

Futamura and the center’s fiscal manager Sara Fritts said that the menu has stayed quite consistent over the years, with some level of evolution.

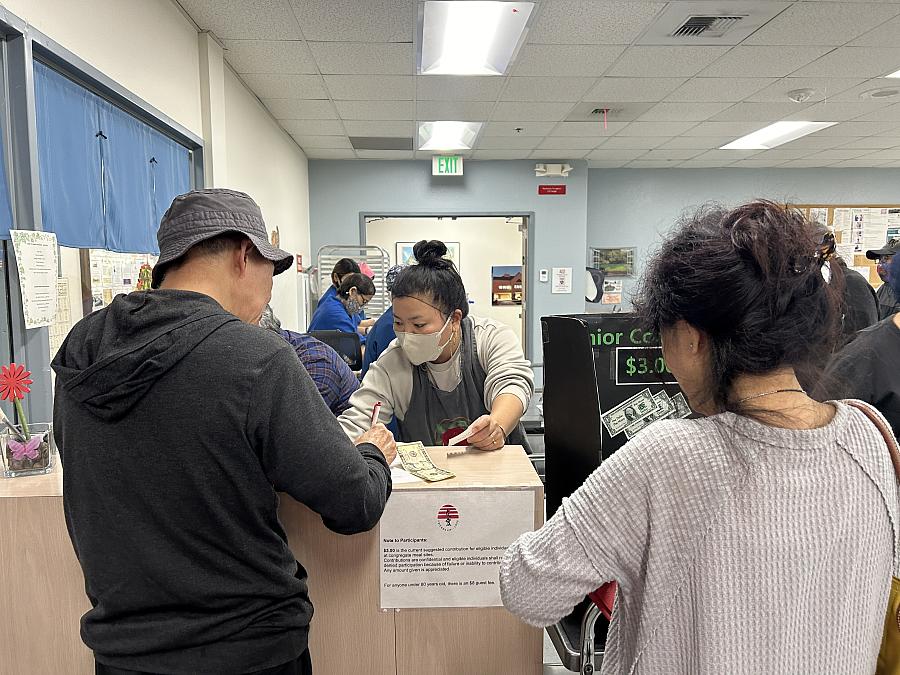

Yu-Ai Kai’s nutrition site manager Maya Futamura taking cash payments and names for the senior lunch on Nov. 11, 2024.

Photo by Jia H. Jung

The newest addition was unagi (うなぎ), eel, procured through leading Asian food distributor JFC International.

“I said it’s actually really easy, because all you do is warm it and slap it on a dish, you know? Whereas, with other things, you have to chop vegetables, chop meat, cook it, season it. But with unagi, it’s super easy – it’s just really expensive,” Futamura said.

Yu-Ai Kai could afford the eel because of a requirement to spend a minimum of 25% of their total kitchen budget on food – one that they were accidentally undershooting.

The seniors went wild for “eel day.” Futamura and Fritts said they also savor other fish dishes, like baked salmon, baked mackerel, and fish ‘n’ batter.

Yu-Ai Kai regular and SNP volunteer Norm Ishikawa, left, and Maya Futamura, right, decompressing after lunch.

Photo by Jia H. Jung

Just before 11:30 a.m., Futamura took her place at the register next to longtime community member and volunteer Norm Ishikawa. Together, they greeted everyone by name and collected cash contributions for lunchtime – a suggested $3 for county residents and $8 for visitors.

Futamura and Fritts confirmed that no one was ever turned away for lack of funds and that Yu-Ai Kai’s lunch bunch were good at paying. Neighboring lunch programs received average contributions of 50 cents, while their average was $2.

Everyone kept one another accountable, by way of socializing with familiar faces in a place with history even richer than the food.

Large social groups, smaller cadres of Japanese speakers, a couple keeping to themselves, and mixers occupied the round tables in the dining hall.

SNP volunteers Sue Yamamoto and Eric Chikasuye strategize across from the Meals on Wheels packing station.

Photo by Jia H. Jung

The servers ferried around dishes of coleslaw and pots of hot green tea. The cooks and additional volunteers packed lunches for Meals on Wheels delivery drivers who stood by, waiting to fill their insulated packs.

Today’s meal was o tanoshimi gyūdon (お楽しみ牛丼 ), a “Surprise Beef Bowl” of savory brisket and fresh green peas over short-grained white rice, topped with menma (メンマ) fermented bamboo shoot slices and beni shōga (紅しょうが ), a type of tsukemono (漬物) Japanese pickle made of ginger strips steeped in umezu (梅酢), the juice of umeboshi (梅干し) – brined ume (梅) plums.

Little cartons of 1% low-fat Clover dairy farm milk sat in green plastic crates or in unattended clusters on the tables. Fritts sighed – the county kept encouraging milk at lunch but most of the lunchers, lactose-intolerant, had to give their milk away.

“I think our stomach is different from Caucasian people, probably,” said Cindy(Fumiko) Ichikawa, a Yu-Ai Kai regular with both osteoporosis and lactose intolerance.

“Surprise Beef Bowl” (お楽しみ牛丼): savory brisket and fresh green peas over short-grained white rice, topped with menma (メンマ) fermented bamboo shoot slices and beni shōga (紅しょうが ), a type of tsukemono (漬物) Japanese pickle made of ginger strips steeped in umezu (梅酢), the juice of umeboshi (梅干し) – brined ume (梅) plums.

Photo by Jia H. Jung

A whole table of “Surprise Beef Bowl” (お楽しみ牛丼) entrees await SNP staff.

Photo by Jia H. Jung

Alex Yamato sat with Ichikawa and Haru Ueda, who has been a regular at the Center since its opening 50 years ago.

“They all tell me this is the best,” Yamato said, citing the word-of-mouth reputation of Yu-Ai Kai’s Asian lunches. Yes, he had heard about “eel day,” but had yet to get in off the waitlist, not even when he called two weeks ahead.

Carl Sasaki was the newest old-timer.

He had lived in San Jose since 1991 but had no idea about Yu-Ai Kai or its services until 2020, while seeking programs for his aging mother. But before his mother could begin participating, she passed away.

Sasaki called Futamura and said that his mother would not be able to join Yu-Ai Kai after all. Futamura expressed her condolences and informed him that, if he was 60 or over, he could get involved himself, starting with the senior lunches.

From left to right, lunchers Alex Yamato, Carl Sasaki, Haru Ueda, and Cindy (Fumiko) Ichikawa.

Photo by Jia H. Jung

Since then, Sasaki has seen it all – social distancing with six-foot demarcations all around, takeout meals, and of drive-through pickups. He tried other lunch programs. There was a program closer to where he lived but he had not visited it yet. The menu there was almost wholly Western and he didn’t know the folks there. But at Yu-Ai Kai, he always knew what he was going to get.

“You eat the food, you know it’s fresh. It’s like going to a restaurant. Where can you get a meal for three dollars? Nowhere,” he said.

Huge center, universe of flavors

Just a 15-minute drive north of Yu-Ai Kai is the India Community Center (ICC) of Milpitas, also in Santa Clara County, which is home to the largest Indian community in the country.

Manoj Goel, the new CEO as of six months ago, walked AsAmNews down the long, sunlit halls of the massive center, pointing out preschool and language classrooms, dance studios, a free robotics equipment closet and lab for children of all backgrounds, and rooms where seniors often arrive before lunchtime to meditate or work up an appetite over rounds of table tennis.

ICC operations and membership Som Sharma, left, with Lata Malviya and volunteer servers Usha Shah and Usha Tandon to his right.

Photo by Jia H. Jung

“Seniors feel isolated. They come here, they talk their language, they eat their kind of food. They feel they stop aging when they come here. They become their child self,” Goel smiled.

Most of the lunchers were in their eighties and nineties, and as with Yu-Ai Kai, they had recently celebrated the 100th birthday of a community member.

Here, too, seniors can enjoy a hot meal for the suggested contribution of $3 for residents and $8 for guests, and no one will be turned away. On peak days, 80 to 100 Indian elders show up to enjoy the vegetarian Indian menu.

A sampler of Monday’s thali (थाली) offerings, clockwise: basmati rice (बासमती चावल) and chapati (चपाती), chaas (छास) spiced buttermilk and a piece of a sweet, bhindi do pyaza (भिंडी दो प्याजा), North Indian stir-fried okra and caramelized onions, urad dal makhani (उड़द दाल मखनी) spicy black lentil curry, and kachumber (कचुम्बर) salad.

Photo by Jia H. Jung

At the beginning of the lunch hour, Lata Maviya, ICC staff member, stood in a row with volunteers, doling out the day’s fare onto compartmentalized metal thali (थाली) trays. Steaming basmati rice (बासमती चावल) and a flatbread,chapati (चपाती), along with a creamy urad dal makhani (उड़द दाल मखनी) black lentil curry and bhindi do pyaza (भिंडी दो प्याजा), a North Indian dish of stir-fried chopped okra with caramelized onions. The accompaniments included a cup of chaas (छास) spiced buttermilk and kachumber (कचुम्बर) salad made with diced cucumbers, tomatoes, and onions.

Goel sat at a table and a woman named Usha Shah joined him. They reminisced about their hometowns. Goel was from Roorkee, 100 miles north of New Delhi in the Haridwar district of the Indian state of Uttarakhand, at the gateway to the Himalayas.

Shah was from Gujarati state, 669 miles to the southwest of Roorkee near the Northwest coast of India. She had brought homemade sweets and amrood ki khatti meethi sabji (अमरूद की खट्टी मीठी सब्जी), a tangy guava curry to share with other patrons.

Usha Shah from Gujarati, sharing her own homemade amrood ki khatti meethi sabji (अमरूद की खट्टी मीठी सब्जी) guava curry and sweets to enhance the SNP lunch.

Photo by Jia H. Jung

Som Sharma, ICC’s operations and membership manager, also took a seat after helping serve lunch. He was responsible for maintaining senior satisfaction, consulting with county nutritionists, and communicating with the cooks of the in-house Madhuban Café that churned out SNP meals while also selling snacks and prepared foods to the general public.

“They’ve been eating Indian food all their lives,” Sharma said. “Food keeps them united and when they sit here, they mingle,” he said.

Malviya said that the lunch program originated because people were already spending half the day at the center while participating in its programs and getting hungry. A local Indian restaurant used to provide the senior lunches before ICC took the menu into its own hands.

ICC cooks hard at work in the Madhuban Café kitchen.

India Community Center

Operations and membership manager Som Sharma, left, and Madhuban Café owner Ashwini Kumar, right.

Photo by Jia H. Jung

India Community Center at 525 Los Coches Street in Milpitas, Calif.

Photo by Jia H. Jung

ICC’s mural brightens up a rainy day.

Photo by Jia H. Jung

Attendance grew steadily over the years, necessitating a move from the center’s kitchen to Madhuban Café. Recently, a record 400 people attended ICC’s Diwali lunch.

She said that some people donated more than the suggested amount, helping to balance out costs.

“Most of them can afford the food because they live with their kids and get money from the county,” said Malviya.

Ashwini Kumar, Madhuban Café’s owner, told AsAmNews he had applied to get the congregate lunch food into the Meals on Wheels delivery program but had been rejected by the county. He had no idea why. He said that he and ICC were keen on getting their food to more people, especially those who could not come to the center themselves.

Lata Malviya, left, with her lunch companions Nilima Chahela, center, and Usha Tandon, right.

Photo by Jia H. Jung

Vendors mainstreaming Asian foods in the Bay’s SNPs

Various Santa Clara SNP menus also offer Vietnamese, Portuguese and other cuisines through the involvement of culturally based community organizations.

Centers can also partner with vendors to expand their offerings through SNPs and charities.

A 15-minute drive south of Yu-Ai Kai is the Campbell Community Center. There, pan-Asian influences grace a more general SNP menu, thanks to an Asian-owned partner called Moonstar.

Daisy Li, Moonstar’s founder and vice president, decided she wanted to go into the food industry when she was just a little kid from Hong Kong growing up in Toronto, Canada. One day, she saw a chocolate fountain at a buffet and vowed to own her restaurant when she grew up, complete with a font of melted sweets for kids like herself.

In 1991, Li and her husband opened up the Moonstar seafood buffet in San Francisco before moving the business to Daly City. In Spring 2021, the business closed its 30-year chapter as a buffet and centralized its operations in an 8,000-square-foot facility by a canal flowing through the spacious industrial district of South San Francisco.

Moonstar’s Daisy Li.

Photo by Jia H. Jung

Li, who had purchased the building just two years before in 2019, told SFGATE that the pandemic was just speeding along decisions she had already made to serve the needy in her community.

Now, instead of serving kids chocolate at a buffet, she wanted to take care of seniors through MoonChef, a service partnering with 25 to 30 organizations including SNP sites.

Li also incorporated Moonstar Charitable Organization as a 501(c)(3) that converts donated ingredients from wholesalers, food pantries, and in-kind donors into hot meals.

Li’s daughter, Ariel Ng, and Ng’s husband Caleb Chen, also work at Moonstar Charitable. They began working with the company as young teenagers and returned after various career experiences.

Schedules on the wall at Moonstar’s kitchen compound in South San Francisco.

Photo by Jia H. Jung

“There’s a lot of food insecurity – people haven’t realized it yet. Not having to worry about food is a luxury,” said Chen, while giving AsAmNews a tour of the company’s industrial-scale kitchens and its gigantic equipment, walk-in refrigerators, rolling Styrofoam tray shelves, and a fleet of Mercedes-Benz delivery trucks.

In the past month, Moonstar supplied nearly 65,000 catered and donated meals to 19 consistent customers and beneficiaries, and more to emergency and short-term recipients. For instance, Yu-Ai Kai ordered its lunches from MoonChef while remodeling their kitchen.

Tina Wong-Erling, senior services supervisor at Campbell’s recreation and community services department, first learned about MoonChef’s senior catering through work with Asian Americans for Community Involvement (AACI) in San Jose.

In 2018, the city contracted MoonChef to introduce one Chinese-style Asian lunch a week to start. This coincided with Santa Clara County’s transportation incentives for seniors headed to SNP centers. Campbell went on to expand MoonChef’s menu to Tuesdays, Wednesdays, and Thursdays.

Moonstar’s operation manager Man Suen, building senior-healthy menus.

Photo by Jia H. Jung

“It’s a great partnership. They really do provide good quality meals – quality and quantity,” Wong-Erling said.

She estimates that Campbell’s Asian lunches have resulted in a roughly 50% increase in the center’s attendance by Chinese, Korean, and Vietnamese elders.

Next on the menu for senior nutrition programs

The demand for more fine-tuned senior nutrition options is increasing as seniors’ needs and diversity continue to grow.

It remains to be seen whether funding can keep up with the imminent demand.

“We’re one of the original sites – I don’t foresee threats of discontinuing the program,” Wong-Erling told AsAmNews in a phone call. The city provides 60% of the funds for the program; the county contributes 40%.

The federal government cut $8 million – 0.8% – of the nutrition program this year. But for California, there may be a silver lining.

Elizabeth Rodriguez, senior director of operations at the Sourcewise nonpartisan 501(c)(3) nonprofit, told AsAmNews it has an open Request For Proposals (RFPs) for potential new SNP providers with innovative ideas for reaching more seniors. The deadline for applications is December 2nd.

Sourcewise has been Santa Clara County’s awarded bidder for federal OAA funds since 1973 and oversees all contracts related to federal Title III C-1 (congregate senior lunch) and Title III C-2 (Meals on Wheels) funding.

Rodriguez said that the $250,000 that Sourcewise is ready to distribute to new SNP providers is in part supported by state funding from the Modernizing Older Californians Act.

Sourcewise is mandated to disseminate information to invite the submission of proposals from community organizations in a general circulating newspaper at least 30 days before the proposal’s due date.

But Rodriguez said that the biggest hurdle to applying can be filling out the proposal. Rodriguez said that the disadvantage of inexperience may be keeping Sourcewise from identifying candidates that could provide exactly what seniors throughout the county need.

She and the Sourcewise leadership are discussing how to expand outreach and help coach applicants who may not have responded to RFPs before.

“We understand that there are local supporters who would do it better than anybody else and know what their communities want,” Rodriguez said. “We know American cuisine isn’t everyone’s cup of tea and that might be why they aren’t accessing these services. We don’t want any unmet needs because of that.”

Sourcewise is receiving applications until Dec. 2. To receive news about future Sourcewise funding opportunities, email area planner Dustin Gordon at dgordon@mysourcewise.com.