Dear Cleveland: Training with police gave us a new perspective, but we still have questions

This reporting is supported by the University of Southern California Center for Health Journalism National Fellowship.

Other stories in the series include:

Dear Cleveland: Help us improve police relations and our "life skills"

Dear Cleveland: We're ready to talk, will you take us seriously?

Dear Cleveland: To learn, you first have to listen

Dear Cleveland: Seeking young voices on life in the city and how to make it better

Tim Harrison, Special to The Plain Dealer

By Chantal Brown, 17

CLEVELAND, Ohio -- I do not feel like listening to these murderers today.

I hit the repeat button on this thought in my head as I drove with some of my fellow council members from the downtown building where we worked to the West Side to visit the training grounds for Cleveland's police academy.

I became even more skeptical when I saw how secluded the training place was, in a woodsy area in a valley behind a couple of houses.

For me it was important to be a part of the group that volunteered to learn more about the police, while the others stayed back and worked on an approach to teaching life skills.

My neighborhood has too many candlelight vigils for victims of police brutality or from neglect or incompetence from law enforcement who were not around enough to prevent the situations in the first place.

I had seen enough videos and distraught mothers to believe one thing; whether or not they pulled the trigger, the police were murderers.

I aspire to be a lawyer and eventually a judge who works to iron out the kinks in our justice system.

When we arrived, we went into a classroom that could fit the average grade school class. Instead of posters about how to add two plus two, we saw instructions on how to aim and fire.

Our host, Cleveland Police Chief Firearms Instructor Sgt. Kevin Campbell, was open to our questions.

It was clear that the main point he wanted us to consider was:"What would you do, if it came down to your life or theirs?"

His officers demonstrated for us the power, intensity and accuracy of each kind of gun available to them.

It was an up-close introduction to all of the guns in an officer's arsenal.

We also toured the bulletproof-walled paint ball-splattered tack house that is used to train officers for building searches.

Each stain represented a place where a trainee had shot in the building believing that they caught a culprit. Our group of seven could barely fit in the structure comfortably, which made me notice how little it was. How could an officer be confident in their search for a gunman and they have no clue of what would be around each corner?

The most powerful piece of training equipment that we saw was the virtual simulator.

Real weapons were programmed into a software that projected people in realistic and dangerous situations.

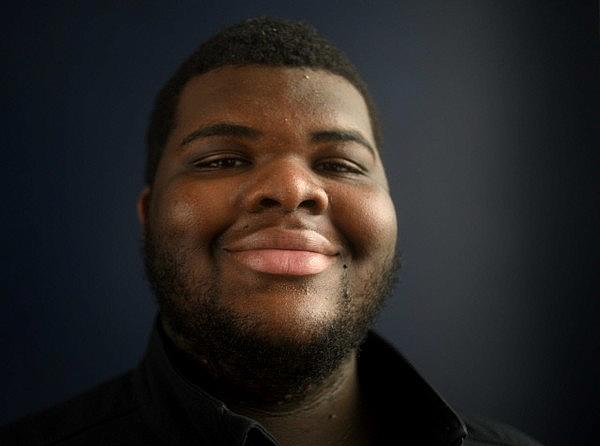

One of our council members, Derin Robinson, 19, volunteered to try the simulation.

Empowering Youth Exploring Justice (EYEJ) Impact 25 Youth Council member Derin Robinson wants to become a police officer and volunteered to try a training simulation at the police training facility. Photo by Tim Harrison/Special to The Plain Dealer

Derin is big, larger than most of the officers be hopes to join on Cleveland's police force one day. He's a senior at Martin Luther King Jr. high school and in the Law Enforcement Career Pipeline Program there.

On a video screen, the simulator projected to Derin what looked like a western highway. A car was parked on a dusty road. A few feet away from the car was a distraught middle-aged white male. The man huffed and puffed as he leaned over the highway barriers, intent on jumping into the abyss on the other side.

Derin spoke to the man calmly, his tone comparable to a kindergarten teacher trying to convince her students to take their nap.

His actions were enough to get the man down. Just as Derin's own breathing began to slow back down we saw the man on the screen reach into his pocket and pull out a gun.

Derin, slightly flustered, pulled his trigger. We all watched as the 'pops' transferred onto the screen penetrating through the man's shirt as he fell onto the ground.

After it was over, we all re-watched what had happened in slow motion on a video monitor.

Derin had shot the man with the gun at least three different times!

Cleveland Police Community Policing Bureau Commander Johnny Johnson talks with EYEJ Youth Council members about their ideas for solutions to improve relationships between young people and the police.

Many of us were in shock. We reflected on earlier discussions we had when we first decided police accountability was a prominent topic to cover and about these types of aggressive shootings involving the police.

We started to discuss: How many of us would have taken the same action Derin did?

Some felt strongly it was wrong to shoot a person more than needed to incapacitate them. Others understood the action he took.

That day, we learned a number of things. We learned that officers have to make split-second decisions where they must decide whether to take a life or to protect the safety of others and to preserve their own.

Also that the officers are overworked and the department doesn't have enough of them.

Most officers have families and policing has one of the highest divorce rates overall. Hearing about the strain a "job" can put on their personal lives created a sort of empathy.

In my head I imagined myself not only being the child of an officer but growing to become a police officer and my family breaking up because of my career choice.

It was a depressing thought.

I also thought that no matter the stress it causes, there isn't an excuse for performing your job poorly.

I personally walked away realizing that not all police were "murderers" out to kill "criminals" unnecessarily. But what was done to stop the ones who were?

Despite any skepticism, we decided to tell the larger group that part of the solution might be for more young people to gain the same insights we did by introducing them to the police training process through mandatory field trips or even lunches with officers.

What we didn't know was if the police, the ones in charge, would agree?

[This story was originally published by The Plain Dealer.]